Season Extension Techniques for Market Gardeners

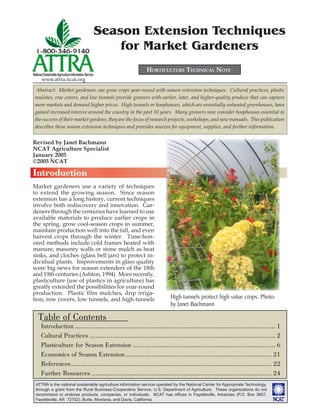

- 1. ATTRA is the national sustainable agriculture information service operated by the National Center for Appropriate Technology, through a grant from the Rural Business-Cooperative Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. These organizations do not recommend or endorse products, companies, or individuals. NCAT has offices in Fayetteville, Arkansas (P.O. Box 3657, Fayetteville, AR 72702), Butte, Montana, and Davis, California. National SustainableAgriculture Information Service www.attra.ncat.org Season Extension Techniques for Market Gardeners HORTICULTURE TECHNICAL NOTE Abstract: Market gardeners can grow crops year-round with season extension techniques. Cultural practices, plastic mulches, row covers, and low tunnels provide growers with earlier, later, and higher-quality produce that can capture more markets and demand higher prices. High tunnels or hoophouses, which are essentially unheated greenhouses, have gained increased interest around the country in the past 10 years. Many growers now consider hoophouses essential to the success of their market gardens; they are the focus of research projects, workshops, and new manuals. This publication describes these season extension techniques and provides sources for equipment, supplies, and further information. Introduction Market gardeners use a variety of techniques to extend the growing season. Since season extension has a long history, current techniques involve both rediscovery and innovation. Gar- deners through the centuries have learned to use available materials to produce earlier crops in the spring, grow cool-season crops in summer, maintain production well into the fall, and even harvest crops through the winter. Time-hon- ored methods include cold frames heated with manure, masonry walls or stone mulch as heat sinks, and cloches (glass bell jars) to protect in- dividual plants. Improvements in glass quality were big news for season extenders of the 18th and 19th centuries.(Ashton, 1994) More recently, plasticulture (use of plastics in agriculture) has greatly extended the possibilities for year-round production. Plastic film mulches, drip irriga- tion, row covers, low tunnels, and high tunnels Revised by Janet Bachmann NCAT Agriculture Specialist January 2005 ©2005 NCAT Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 Cultural Practices ................................................................................................... 2 Plasticulture for Season Extension ............................................................................ 6 Economics of Season Extension.............................................................................. 21 References........................................................................................................... 22 Further Resources ................................................................................................ 24 High tunnels protect high value crops. Photo by Janet Bachmann

- 2. PAGE 2 //SEASON EXTENSION TECHNIQUES FOR MARKET GARDENERS or hoophouses, help to protect crops from the weather. The use of plastic in horticultural crop production has increased dramatically in the past decade. High tunnels are springing up around the country, as more and more market gardeners see them as essential to their operations. Benefits from year-round production include year-round income, retention of old customers, gain in new customers, and higher prices at times of the year when other local growers (who have only unprotected field crops) do not have pro- duce. Other potential benefits of season extension technologies are higher yields and better quality. In addition, with year-round production you can provide extended or year-round employment for skilled employees whom you might otherwise lose to other jobs at the end of the outdoor grow- ing season. Disadvantages include no break in the yearly work schedule, increased management demands, higher production costs, and plastic disposal problems. Eliot Coleman, a market gardener in Maine who uses various techniques to grow vegetables year-round, summarizes the contribution season extension makes to sustainability. . . . to make a real difference in creating a local food system, local growers need to be able to continue supplying “fresh” food through the winter months . . .[and] to do that without markedly increasing our expenses or our consumption of non-renewable resources.(Coleman, 1995) The information in this publication and in the materials listed as Further Resources can help you analyze the benefits and costs of season ex- tension techniques on your farm. Cultural Practices Almost all plants benefit from increased early- and late-season warmth. Many cultural tech- niques can modify the microclimate in which a crop is grown, without using structures or covers, though some of these techniques require long- term planning. Site Selection Garden site selection is very important for ex- tended-season crop production. Cold air, which is heavier than warm air, tends to settle into val- leys on cold nights, limiting the growing season there. In areas of relatively low elevation, a higher-elevation site only a few miles away can easily have a 4- to 6-week longer growing season. A site on the brow of a hill, with unimpeded air drainage to the valley below, would be ideal where season extension is an important consider- ation. (In more mountainous areas, temperatures drop as elevation increases.) In northern states, land with a southern aspect is the best choice for early crops, as south-facing slopes warm up sooner in the spring. Further- more, the closer to perpendicular the southern slope is to the angle of sunlight, the more quickly it warms. South-facing slopes may not be advantageous in the southern U.S., where soil is likely to be relatively shallow, poor in soil fertility, and low in accumulated organic matter. If there has to be a choice between a sunnier aspect and native soil quality, the latter wins out, especially in the South, where winters and early springs are not as cold as in the North. Soils and Moisture Content Soils can affect temperature because their heat storage capacity and conductivity vary, depend- ing partly on soil texture. Generally, when they are dry, sandy and peat soils do not store or con- duct heat as readily as loam and clay soils. The result is that there is a greater daily temperature range at the surface for light soils than for heavier Related ATTRA Publications Compost Heated Greenhouses Greenhouse and Hydroponic Vegetable Resources on the Internet Low-cost Passive Solar Greenhouses Root Zone Heating Solar Greenhouse Resource List Specialty Lettuce and Greens: Organic Production Scheduling Vegetable Plantings for Continuous Harvest

- 3. // SEASON EXTENSION TECHNIQUES FOR MARKET GARDENERS PAGE 3 soils, and the minimum surface temperature is lower. Darker soils often absorb more sunlight than light-colored soils and store more heat. Consequently, areas with lighter-colored soils (and no ground cover) are more prone to frost damage.(Snyder, 2000) Bare soil absorbs and radiates more heat than soil covered with vegetation. Although the radiated heat helps protect against frost, cover crops pro- vide many other benefits. Mowing to keep the ground cover short provides a compromise. In addition, moist soil absorbs and radiates more heat than dry soil, because water stores consider- able heat. To maximize this effect, water content in the upper one foot of soil where most of the change in temperature occurs must be kept near field capacity.(Snyder, 2000) Irrigation Overhead sprinklers, furrow, and drip irrigation can be used to protect crops from frost. Sprinklers are turned on when the temperature hits 33°F. When the water comes in contact with plants, it begins to freeze and release heat. As ice forms around branches, vines, leaves, or buds, it acts as an insulator. Although the level of protection is high, and the cost is reasonable, there are several disadvantages. If the system fails in the middle of the night, the risk of damage can be quite high. Some plants are not able to support the ice loads. Large amounts of water, large pipelines, and big pumps are required. Water delivered to a field via drip and furrow irrigation, however, can keep temperatures high enough to prevent frost damage without the same risks.(Evans, 1999; Snyder, 2000) Smudge Pots and Wind Machines Smudge pots that burn kerosene or other fuels are placed throughout vineyards or orchards to produce smoke. The smoke acts like a blanket to keep warm air from moving away from the ground. The smoke is also a significant source of air pollution, and smudge pots are rarely used anymore.(Atwood and Kelly, 1997) Today, using oil and gas heaters for frost control in orchards is usually in conjunction with other methods, such as wind machines, or as border heat (two or three rows on the upwind side) with undertree sprin- kler systems.(Evans, 1999; Geisel and Unruh, 2003; Snyder, 2000) Specialty cut flower growers Pamela and Frank Arnosky in Texas have a lot of experience deal- ing with wide fluctuations in temperature, and in a recent article they describe various methods for protecting high-value crops. They give this description of wind machines. Cold air is heavier than warm air, and on a still night, the cold air will sink below the warm air and actually flow downhill. This is what happens when people say you have a “frost pocket.” As cold air flows downhill, it gets trapped in valleys and low spots. Even a row of trees can hold cold air in a pocket. Unless your farm is perfectly flat, you probably have a frost pocket somewhere, and you can avoid trouble by planting that spot later in the spring, or with hardy plants. As the cool air sinks, the warm air is pushed up, and settles in a layer just above the field as an “in- version layer.” This is a pretty neat phenomenon Orchard-Rite Ltd. wind machines protect crops from frost, and with added Agri-Cool™ System protects apple crops from hot weather. Photo courtesy of Orchard-Rite, Ltd.

- 4. PAGE 4 //SEASON EXTENSION TECHNIQUES FOR MARKET GARDENERS that occurs on perfectly still nights. The inversion layer can be quite warm, and often is not very far off the ground. . . . In big orchard operations, you will often see giant fans on towers among the trees. These fans are there to take advantage of the trapped inversion zone. They mix the warm air above and prevent the cold air from settling among the trees. They are super- expensive, but so is losing a crop. Fans like this only work in a still, radiational frost.(Arnosky, 2004) More information about wind machines is available from contacts listed under Further Resources. Windbreaks Windbreaks decrease evaporation, wind damage, and soil erosion, and provide habitat for natural enemies of crop pests. They are also an important part of season extension, helping to create pro- tected microclimates for early crops. Windbreaks should run perpendicular to (across) the prevail- ing direction of early-season winds.(Hodges and Brandle, 1996) Existing stands of trees can be used, but choose trees for windbreaks carefully, so that shading, competition for water and nutri- ents, and refugia for plant pests do not become problems. Fall-planted cover crops of small grains (rye, barley, winter wheat) can serve as windbreaks the following spring; at plow-down, strips are left standing every 30 to 40 feet and cut or tilled under when no longer needed. Each strip should be the width of a small-grain drill (10 to 12 feet). However, small winter-grains may be too short to constitute an effective windbreak for early spring crops. Top-dressing with compost will help ensure a good stand. Another option is to plant perennial grass windbreaks that will maintain protection through winter and early spring. These are only general guidelines; experimen- tation and adaptation are necessary to find the best solution for a particular situation. Other windbreaks include snow fences, commercial windbreak materials, brush piles, stone walls, old fencerows or hedges, shrubs, berry brambles, and even overgrown ditches. In any case, wind- breaks should not be allowed to interfere with down-slope air drainage and should allow for some circulation to prevent air stagnation and frost pockets.(Lamont, 1996; Hodges and Brandle, 1996) Cultivar Selection Cultivar selection is important for early crop production. The number of days from planting to maturity varies from cultivar to cultivar, and some cultivars germinate better in cool soil than others. Staggered planting dates can be combined with the use of cultivars spanning a range of ma- turity dates to greatly extend the harvest season for any one crop. Early-maturing cultivars are very important in going for the early market, though in many cases the produce will be smaller. Some later-maturing cultivars also have better eating qualities and yields than earlier cultivars. Information on varieties adapted to your area is available from local growers, seed catalogues, trade magazines, Cooperative Extension, and resources listed at the end of this publication. Brett Grohsgal, who co-owns Even’ Star Organic Farm with his wife, Dr. Christine Bergmark, in southern Maryland, says that seed saving and genetic management are keystones of their winter cropping system. They started with purchased seed, but after several years of careful selection and seed saving, they have their own supply of seed for crops adapted to their harsh local winter weather.(Grohsgal, 2004) Shade Although season extension usually brings to mind an image of protecting plants from the cold, modifying temperatures in mid-summer can also be important. Shade over a bed can create a cool microclimate that will help prevent bolting and bitterness in heat-sensitive crops such as lettuce and spinach, make it possible to grow warm- weather crops in areas with very hot summers, and hasten germination of cool-weather fall crops. Some growers provide cooling shade by growing vines such as gourds on cattle panels or similar frames placed over the beds. Shade fabrics, available from greenhouse- and garden- supply companies, can be fastened over hoops in summer to lower soil temperatures and protect crops from wind damage, sunscald, and drying. Placing plants under 30 to 50% shade in midsum- mer can lower the leaf temperature by 10°F or more.(Bartok, 2004) Commercial shade fabrics are differentiated by how much sunlight they block. For vegetables like tomatoes and peppers, use 30% shade cloth in areas with very hot summers. For lettuce, spin- ach, and cole crops, use 47% in hot areas, 30% in northern or coastal climates. Use 63% for shade-

- 5. // SEASON EXTENSION TECHNIQUES FOR MARKET GARDENERS PAGE 5 loving plants. (The maximum shade density—80%—is often used over patios and decks to cool people as well as plants).(Peaceful Valley, 2004) See the ATTRA publication Specialty Lettuce and Greens: Organic Production for more on growing let- tuce in hot weather. Shade houses can also provide frost protection for perennials and herbs during winter. Temperatures inside can be as much as 20°F higher than outdoors.(Bartok, 2004) Silver Tufbell from Peaceful Valley Farm Supply is a specially devel- oped alternative to woven shade fabric. It is impregnated with sil- ver-finish aluminum for very high light as well as infra-red (heat) reflection. This, combined with a close weave, gives 45% shading during the day, but reflects heat back to the crop at night. Silver Tufbell is especially suited for sun- and heat-sensitive crops. The reflective surface also deters many pests, espe- cially whiteflies and aphids, from approaching the crop.(Peaceful Valley, 2004) Steve Upson, who has been working with hoop- houses at the Noble Foundation in Oklahoma, began installing Kool-Lite Plus brand poly film, in attempts to keep the houses cooler in the summer. He says this film, which blocks solar infra-red radiation, has kept temperatures up to 12°F cooler during the afternoon and evening. He says although you can expect to pay 75% more for Kool-Lite Plus, the additional cost can be justified, considering the costs associated with the use of shade fabric.(Upson, 2002) Transplants Use of transplants (versus direct seeding) is another key season-extension technique. Some crops have traditionally been transplanted, and recent improvements in techniques have expand- ed the range of crops suited to transplant culture. Transplants provide earlier harvests by being planted in a greenhouse several weeks before it is safe to direct-seed the same crop outdoors. If a grower uses succession planting or multiple cropping (i.e., follows one crop with another in the same spot), transplants provide extra time for maturing successive crops. Transplants hit the ground running, with a 3 to 4 week head start on the season. Transplanting aids in weed control by getting a jump on the weeds and by quickly form- ing a leaf canopy to shade out germinating weed seedlings. Transplants also avoid other pests that attack germinating seeds and young seedlings, such as fungal diseases, birds, and insects. Multiple Cropping Planting more than one crop on the same bed or row in one year intensifies the cropping schedule. Immediately after one crop is harvested, another is planted. Dr. Charles Marr and Dr. William Lamont (1992) list the following advantages of multiple cropping, and conclude “if you can’t triple crop, then you certainly can consider double cropping.” • Cost savings. Money spent on plastic mulch, drip irrigation lines, and other equipment covers three crops instead of one. • Higher gross per acre. In his triple cropping field trials, Lamont realized gross returns of $13,000 to 15,000 per acre. • Improved cash flow. Multiple harvests throughout the season can provide income at critical times and distribute returns more evenly over a longer period. • Risk management. Multiple cropping pro- vides a hedge against the loss of a crop to freezes, hailstorms, and other crises. • Increased productivity. Small areas of land are thus made more productive, a great boon in areas where cropland is scarce or costly. Plastic mulch can increase yield and quality of potatoes. Photo courtesy Penn State Center for Plasticulture.

- 6. PAGE 6 //SEASON EXTENSION TECHNIQUES FOR MARKET GARDENERS Table 2. Examples of triple cropping sequences Spring Summer Fall Cole crops Summer squash Tomatoes Lettuce Cucumbers Tomatoes Sweet corn Cucumbers Tomatoes (Marr and Lamont, 1992) Table 1. Spring-Fall Planting Sequences for North Carolina Please note that crops in the same family never follow each other in the same field or bed in the same year. The same rule applies to triple cropping sequences. Spring Fall Peppers Summer squash, cucumbers, or cole crops Tomatoes Summer squash, cucumbers, or cole crops Summer squash Tomatoes or cole crops Eggplant Summer squash Cucumbers Tomatoes Muskmelons Tomatoes Watermelons Tomatoes Honeydews Tomatoes Cole crops Summer squash, pumpkins, muskmelons, or tomatoes Cauliflower Summer squash, pumpkins, muskmelons, or tomatoes Snap beans Summer squash, pumpkins, muskmelons, or tomatoes Southern peas Summer squash, pumpkins, muskmelons, or tomatoes Lettuce Summer squash, pumpkins, muskmelons, or tomatoes Sweet corn Summer squash, tomatoes, or cucumbers Strawberries Tomatoes, summer squash, cucumbers, or pumpkins (Sanders, 2001) Table 1 shows examples of dou- ble cropping sequences from North Carolina.(Sanders, 2001) Table 2 shows examples of triple cropping sequences suitable for plasticulture in Kansas.(Marr and Lamont, 1992) For related information, see the ATTRA publication Scheduling Vegetable Plantings for Continuous Harvest. • Cleaner, higher-quality produce • More efficient use of water resources • More efficient use of fertilizers • Reduced soil and wind erosion (though erosion may increase in un-mulched paths between rows) • Potential decrease in disease • Better management of certain insect pests • Fewer weeds • Reduced soil compaction and elimination of root pruning • The opportunity for efficient double or triple cropping (Lamont, 1996) Plasticulture for Season Extension During the past 10 years there has been an explo- sion in the use of plastics in agriculture. The term “plasticulture” is used to describe an integrated system that includes—but is not limited to—plas- tic film mulches, drip irrigation tape, row covers, low tunnels, and high tunnels. Some benefits of a comprehensive plasticulture system include: • Earlier crop production (7 to 21 days earlier) • Higher yields per acre (2 to 3 times higher)

- 7. // SEASON EXTENSION TECHNIQUES FOR MARKET GARDENERS PAGE 7 Disadvantages of Plasticulture: The Disposal Dilemma Costs and management time will both increase with the use of plasticulture, but if it’s done well, the higher productivity and profit should more than compensate. The most serious problems associated with plasticulture have to do with removal from the field and disposal. Machines are commercially available to remove plastic mulch from the field (Zimmerman, 2004; Holland, 2004) and to roll and pack it into bales, but for smaller-scale growers this is probably not an option. Other obstacles to recycling include dirt on the plastic, UV degradation, the high cost of collecting and sorting, and a lack of reliable end- use markets. But recycling technologies and initiatives are evolving. Dr. William Lamont, an advocate of plasticulture, envisions a future when growers will remove, chop, and pelletize field plastics for use as a fuel. Lamont and others at The Penn State Center for Plasticulture are currently testing a heater manufactured in Korea that burns plastic pellets made from waste plastics of all types. Dennis DeMatte, Jr., who as manager of the Cumberland County (New Jersey) Improvement Authority works with New Jersey’s greenhouse plastic film recycling program, stated that since the program was initiated in 1997, the CCIA has recycled approximately 80 percent of the film collected. From 1997 through 2002, the state collected about 1,120 tons of film.(Kuack, 2003) Web sites for more information about recycling agricultural or greenhouse-related plastic products include: The Penn State Center for Plasticulture www.plasticulture.org/newsletters/ASP_April04.pdf Cumberland County Improvement Authority www.ccia-net.com Agriculture Container Recycling Council www.acrecycle.org USAg Recycling Inc. www.usagrecycling.com Cornell University Environmental Risk Analysis Program http://environmentalrisk.cornell.edu/C&ER/PlasticsDisposal/AgPlasticsRecycling/ Plastic Mulches Plastic mulches have been used commercially on vegetables since the early 1960s. Muskmelons, tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers, squash, eggplant, watermelons, sweet corn, snap beans, southern peas, pumpkins, and okra will all ripen earlier and produce better yields and fruit quality when grown on plastic mulch. Plastic mulches have helped growers in extreme northern and high-altitude climates harvest heat-loving crops that were previously impos- sible for them to grow. In the northeastern U.S. small acreages of sweet corn are established by transplanting into plastic mulch for an early crop. Broccoli, cauliflower, pumpkin, and winter squash can also be established as transplants into plastic, if earliness and reduced environmental stress are required. In the Southwest, spring mel- ons are direct seeded then covered with plastic strips to accelerate germination and develop- ment. At the three to four leaf stage, the plastic is removed.(Guerena, 2004) Small-scale market gardeners will probably lay down plastic mulch by hand. Tim King, market gardener near Long Prairie, Minnesota, has been using a system of raised beds, drip irrigation, plastic mulch, and fabric row-cover tunnels since 1986. He says that although doing everything by hand is very labor intensive, they are very pleased with the flexibility this gives them to “hybridize” the parts of the system in various ways. It also al-

- 8. PAGE 8 //SEASON EXTENSION TECHNIQUES FOR MARKET GARDENERS lows them to reuse much of the material a second and even a third season.(King, 2002) Mechanical application can save time. Many growers have found that a simple tractor-pulled mulch layer will reduce overall costs and help ensure a uniform installation that will resist wind damage. Plans are available for a mulch layer that can be built in a farm shop (Thompson et al., 2004), and the machines are also commercially available. They can also be designed to install a drip irrigation line at the same time.(Zimmerman, 2004; Holland, 2004) Plants or seeds can be set through slits or holes in the plastic by hand or with a mechanical transplanter. Labor savings from mechanical transplanters are significant, even on limited acreages. For successful plant establishment with plastic mulch, it is important that beds be level, the plas- tic is tightly laid, drip irrigation tape is placed in a straight line in the center of the bed, and water is applied through the irrigation system immedi- ately after transplanting. Never use plastic mulch without irrigation. Certified organic producers should be aware that organic standards place certain restrictions on the use of plastic mulches. For example, PVC plastics may not be used as mulches or row covers. Also, plastic mulches must be removed from the field before they begin decomposing— which would seem to eliminate photodegradable films from organic production. Plastic mulches are available in a number of col- ors, weights, and sizes for various needs. Many come as 3– to 5–foot wide rolls that can be laid over soil beds with a tractor and mechanical mulch layer. Extensive research with colored mulches has been conducted at the Horticulture Research Farm, Rock Springs, Pennsylvania, by staff of The Pennsylvania State University Cen- ter for Plasticulture. (See Further Resources for contact information.) Black plastic mulch is the most commonly used. It suppresses weed growth, reduces soil water loss, increases soil temperature, and can im- prove vegetable yield. Soil temperatures under black plastic mulch during the day are gener- ally 5°F higher at a depth of 2 inches and 3°F higher at a depth of 4 inches compared with bare soil.(Sanders, 2001) Black plastic embossed film has a diamond-shaped pattern. It has the same advantages as smooth black plastic. The pattern helps to keep the mulch fitted tightly to the bed. For plastic mulch to be most effective, it is important that it be in contact with the soil that it covers. Air pockets act as insulation that reduces heat transfer. Clear plastic mulch will allow for greater soil warming than colored plastic. It is generally used in the cooler regions of the United States, such as New England. Clear plastic increases soil tem- peratures by 8 to 14ºF at a depth of 2 inches, and by 6 to 9°F at a depth of 4 inches.(Orzolek and Lamont, no date) A disadvantage is that weeds can grow under the clear mulch, while black mulch shades them out. Therefore, clear plastic is generally used in conjunction with herbicides, fumigants, or soil solarization. Organic growers may want to experiment with clear plastic to find out whether weeds become a real problem. The mulch’s benefit to the crop may outweigh the competition from weeds.(Coleman, 1995) White, coextruded white-on-black, or silver reflect- ing mulches can result in a slight decrease in soil temperature. They can be used to establish a crop when soil temperatures are high and any reduc- tion in soil temperatures is beneficial. Infrared-transmitting (IRT) mulches provide the weed control properties of black mulch, but they are intermediate between black and clear mulch in warming the soil. IRT mulch is available in brown or blue-green. Redmulchperformslikeblackmulch,warmingthe soil, controlling weeds, and conserving moisture, with one important difference. In Pennsylvania experiments, tomato crops responded with an av- erage 12% increase in marketable fruit yield over a 3-year period. There appears to be a reduction in the incidence of early blight in plants grown on red mulch, compared with plants grown on black mulch. When environmental conditions for plant growth are ideal, tomato response to red mulch is minimal. Other crops that may respond with higher yields include eggplant, peppers, melons, and strawberries.(Bergholtz, 2004) (Red mulch also suppresses nematodes. See the ATTRA publication Alternative Nematode Control.) Additional colors that have been investigated include blue, yellow, silver, and orange. Each reflects different radiation patterns into the canopy of a crop, thereby affecting plant growth and development. Increased yield was recorded for peppers grown on silver mulch, cantaloupe on green IRT or dark blue mulch, and cucum- bers and summer squash on dark blue mulch,

- 9. // SEASON EXTENSION TECHNIQUES FOR MARKET GARDENERS PAGE 9 compared with black. Insect activity can also be affected: yellow, red, and blue mulches increase peach aphid populations; silver repels certain aphid species and whiteflies and reduces or delays the incidence of aphid-borne viruses in crops.(Orzolek and Lamont, no date) Photodegradable film has much the same qualities as other black or clear plastic film, but is formu- lated to break down after a certain number of days of exposure to sunlight. The actual rate of breakdown depends on temperature, the amount of shading from the crop, and the amount of sunlight received during the growing season. Buried edges of the film must be uncovered and exposed to sunlight. Use of photodegradable film eliminates some of the disposal problems associated with regular plastic, but is not with- out problems, and its availability has decreased rather than expanded during the past five years. A representative of one company that no longer offers photodegradable mulch says they discon- tinued the product because the breakdown was not consistent. Photodegradable mulch is not allowed for use in organic production. Biodegradable Mulches Biodegradable plastics are made with starches from plants such as corn, wheat, and potatoes. They are broken down by microbes. Biodegrad- able plastics currently on the market are more expensive than traditional plastics, but the lower price of traditional plastics does not reflect their true environmental cost. Field trials in Australia using biodegradable mulch on tomato and pep- per crops have shown it performs just as well as polyethylene film, and it can simply be plowed into the ground after harvest.(Anon, 2002) Researchers with Cornell Univer- sity also found that biodegradable mulches supported good yields, but the films they used are not yet commercially available in the U.S.(Rangarajan et al, 2003) Bio- Film is the first gardening film for the U.S. market. Made from cornstarch and other renewable resources, it is 100% biodegrad- able. Bio-Film is certified for use in organic agriculture by DEBIO, the Norwegian con- trol and certification body for organic and biodynamic agricultural production, and is available from Dirt Works in Vermont. (See Further Resources.) Paper mulch can provide benefits similar to plastic and is also biodegradable. An innovative group in Virginia carried out on-farm experiments to explore alternatives to plastic. They compared soil temperatures and tomato growth using various mulches, including black plastic, Planters Paper, and recycled kraft paper. Plastic, paper, and organic mulches all improved total yields of tomatoes grown in the trials, when compared with tomatoes grown on bare soil.(Schonbeck, 1995; Anderson, 1995) Recycled kraft paper is available in large rolls at low cost. Participants in the experiment were concerned that it would break down too quickly. To retard degradation, they oiled the paper. This resulted in rather transparent mulch and, as with clear plastic, soil temperatures were higher than under black plastic. Weeds also grew well under the transparent mulch. To reduce weed growth and to keep the soil from becoming too hot, the experimenters put hay over the oiled paper sev- eral weeks after it was laid. Planters Paper is a commercially available paper mulch designed as an alternative to plastic. It comprises most of the benefits of black plastic film and has other advantages. It is porous to water. Left in the soil, or tilled in after the grow- ing season, it will degrade. Tomatoes grown with this mulch showed yields and earliness similar to tomatoes grown in black polyethylene mulch, even though the latter resulted in slightly higher soil temperatures. Planters Paper, however, is considerably more expensive than black plastic. It does not have the stretchability of plastic, and it tends to degrade prematurely along the edges where it is secured with a layer of soil. The paper is then subject to being lifted by the wind. Rebar, old pipe, or stones—rather than soil—can be used to secure the edges.(Bergholtz, 2004) Penn State Center for Plasticulture trial of potatoes grown with colored plastic mulch, drip irrigation, and floating row covers. Photo courtesy Penn State Center for Plasticulture.

- 10. PAGE 10 //SEASON EXTENSION TECHNIQUES FOR MARKET GARDENERS Melons, more and earlier One study, based on three years of field trials in Utah, found that clear plastic mulch increased watermelon yield by 20%, while using the mulch and a row cover increased the yield by 44%, in comparison with melons raised without plasticul- ture. The mulch also allows for earlier planting. Dr. Alvin Hamson, the primary author of the study, recommends covering the cultivated beds with clear plastic a week or two before transplanting. Then set the transplants into slits cut into the plas- tic. The mulch will trap enough heat to protect the melon plants down to an air temperature of 27ºF. Some further tips from Dr. Hamson: Transplant three-week-old seedlings into the field (harden them off first) about the same time apple blossoms open in your area. If you plan to use a floating row cover in addition to the mulch, you can set out transplants a week before apple bloom. Be sure to remove the row cover a week before the melons begin to flower, so that bees can pollinate them, and remove it gradually—leave the cover off for a few more hours each day for a week. Dr. Hamson recommends the same early planting technique for summer squash.(Long, 1996) Another study, done at an experiment station in Connecticut, involved multiple cropping of spe- cialty melon transplants using black plastic mulch and floating row covers. Yields from these beds were up to three times higher than yields from beds planted in plastic mulch without the row cover. The earliest-yielding cultivars in this study were Passport (galia) and Acor (charentais), both developed with shorter days to maturity for use in northern climates. These specialty melons are larger than cantaloupe and fetch a higher price. Accounting for the added expense of row covers, the researchers concluded that “row covers not only increased early fruit and total fruit, but prof- itability is about 6-fold greater when melons are grown for retail or wholesale.”(Hill, 1997) Floating Row Covers Floating row covers are made of spun-bonded polyester and spun-bonded polypropylene and are so lightweight that they “float” over most crops without support. (Crops with tender, exposed growing points, such as tomatoes and peppers, are exceptions. To prevent damage from wind abrasion, the cover should be sup- ported with wire hoops.) The spun-bonded fabric is permeable to sunlight, water, and air, and provides a microclimate similar to the inte- rior of a greenhouse. Plants are protected from drying winds by what amounts to a horizontal windbreak, and the covers give 2 to 8°F of frost protection. In addition to season extension, ad- vantages include greater yields, higher-quality produce, and exclusion of insect pests. Floating row covers are available in various weights ranging from 0.3 to 2 ounces per square yard. The heavier the cover, the more degrees of frost protection it affords. Sizes range from widths of 3 to 60 feet and lengths of 20 to 2,550 feet. Wider covers are more labor-efficient, as there is less edge to bury per covered area. Du- rability is related to weight, type of material, and the additives used. The lightest covers are used primarily as insect barriers. They can protect crops such as cabbage and broccoli from loopers and cabbage worms by excluding the egg-laying moths. Eggplant, radishes, and other favorites of the flea beetle are easily protected by floating row covers. Be sure to rotate crops in fields or beds planted under row covers, since overwintering insects from a previ- ous crop can emerge under the cover.(Hazzard, 1999) Various diseases spread by insect vectors such as aphids and leaf hoppers are prevented as long as the cover remains in place. Disadvan- tages to the lighter covers are that they are easily damaged by animals and are seldom reusable. The lightest covers have a negligible effect on temperature and light transmission. Medium-weight covers are the most commonly available. They are used to enhance early ma- turity, increase early yields and total yields, improve quality, and extend the season or make possible the production of crops in areas where they could not otherwise be grown. They also serve as insect barriers. Crops commonly grown with protection of medium-weight covers include melons, cucumbers, squash, lettuce, edible-pod peas, carrots, radishes, potatoes, sweet corn, strawberries, raspberries, and cut flowers. Heavier covers, those exceeding 1 ounce per square yard, are used primarily for frost and freeze protection and where extra mechanical strength and durability are required for ex- tended-season use. The microclimate created by heavier covers is similar to that created by

- 11. // SEASON EXTENSION TECHNIQUES FOR MARKET GARDENERS PAGE 11 medium-weight covers, but they can be reused for three to four seasons or more. Floating row covers can be installed manually or mechanically. Immediately after transplanting or direct seeding, lay the covers over the area and weigh down or bury the edges. Small-diameter concrete reinforcing bar (rebar), cut to manage- able lengths, is excellent for weighting the edges. Enough slack should be left in the cover to allow the crop to grow. Row covers placed over crops growing on bare soil create a favorable environ- ment for weed germination and growth. Peri- odic removal of the cover for hand cultivation is not practical. Weed control can be a significant problem under row covers, unless they are used in combination with plastic or other mulches. In self-pollinated crops, or leafy vegetables such as lettuce or cabbage, the covers can be left on for most of the production period. One caution when growing tomatoes or peppers under covers is in regard to heat—temperatures that rise above 86°F for more than a few hours may cause blos- som drop.(Wells, 1992) With insect-pollinated crops, such as melons, squash, or cucumbers, the covers must be removed at flowering to allow for insect pollination. The covers may, however, be replaced after the crop has been pollinated. Removing the covers should be considered a hardening-off procedure. Over the course of a few days, keep the covers off for longer and longer periods. Final removal is best done on a cloudy day, preferably just before a rain. Plants will suffer more transition shock if exposed to sun and wind. Floating row covers can be used again in the fall. This some- times involves modi- fying the technol- ogy. When floating row covers are used for spring crops, the covers are removed before the crops ma- ture, while with fall crops the covers re- main on the mature plants. In windy c o n d i t i o n s t h i s sometimes results in abrasion of the plant leaves, which can mar the appearance of a leafy crop. In that case, the cover could be supported on wire hoops or bowed fiberglass rods, so it no longer rubs against the vegetable crop.(Coleman, 1995) Row covers should be stored away from sun- light as soon as they are removed from the field. Many have been treated to resist degradation by UV light; whether or not that is the case, they will last longer if stored carefully in a dark, dry place. Fold or roll the covers in a systematic way to make them easy to unfurl for the next season’s use.(Hazzard, 1999) Hoop-Supported Row Covers (Low Tunnels) Row covers made of clear or white polyethylene are too heavy to float above the crop, so they are supported by hoops. Dimensions vary, but a typical structure is 14 to 18 inches high at the apex and wide enough to cover one bed. They are commonly used in combination with black plastic mulch for weed control. Hoop-supported row covers are often called low tunnels. They offer many of the same benefits as floating row covers, but are not permeable to air or water and are more labor-intensive. There are several types of low tunnels. Slitted row covers have pre-cut slits that provide a way for excessive hot air to escape. At night the slits remain closed, reducing the rate of con- vective heat loss and helping to maintain higher temperatures inside the tunnel. Punched row covers have small holes punched Floating row covers are available in various weights and sizes. Photo courtesy of Ken-Bar.

- 12. PAGE 12 //SEASON EXTENSION TECHNIQUES FOR MARKET GARDENERS about 4 inches apart to ventilate hot air. The punched covers trap more heat than the slitted tunnels. They are best for northern areas and must be managed carefully to avoid overheating crops on bright days. They are useful for peppers, tomatoes, eggplant, most cucurbits, and other warm-season crops that grow upright. Tunnels that use two 3-foot wide plastic sheets stapled together at the top are commonly used by farmers growing trellised crops such as cherry tomatoes, long beans, and bitter melons. These tunnels are more expensive to put up, but they require little equipment investment. Most of the work to put them up is done by hand.(Ilic, 2004) Hoops for supporting slitted or punched row covers are often made from 10-gauge galvanized wire. The pieces are cut to 65 to 75 inches long. Each end is inserted about 6 to 12 inches deep on each side of a row or bed to form a hoop over it. Hoops are spaced 5 to 8 feet apart—or less. Tim King, a market gardener in Minnesota, cuts hoops 3 to 4 feet long and spaces them 2 feet apart in the beds.(King, 2002) The covers are anchored on each edge with soil. Tunnels can be set by hand or with machines that resemble plastic mulch layers. Cold Frames Traditional low struc- tures such as cold frames and cloches are continually be- ing modified by in- novative gardeners and garden supply manufacturers. Al- though cold frames work well in pro- tecting crops in cold weather, construction costs are high com- pared to plasticulture systems. For special situations, many pub- lications contain plans for cold frames, solar pods, and other small portable structures. Solar Gardening, by Leandre and Gretchen Poisson, listed under Further Resources, is one such publication. A more recent article on cold frames can be found in the November 2004 issue of Fine Gardening magazine.(Vargo, 2004) High Tunnels High tunnels, also called hoop houses, have been attracting a lot of attention in the past few years, as more and more market gardeners have come to consider high tunnels essential tools in their operations. A high tunnel is basically an arched or hoop-shaped frame covered with clear plastic and high enough to stand in or drive a tractor through. Traditional high tunnels are completely solar heated, without electricity for automated ventilation or heating systems. Crops are grown in the ground, usually with drip irrigation. Com- pared to greenhouses, high tunnels are relatively inexpensive, ranging in price from $1.50 to $3.00 per square foot—and even less for the Haygrove multibay tunnels discussed below. High tunnels are used extensively in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. Although high tun- nels are not used as much in the United States as in other parts of the world, interest here is growing rapidly. Universities and agricultural organizations around the country are conducting high-tunnel research, market growers are hosting workshops on their farms and at conferences, and more articles are appearing in trade journals and newsletters. Slitted row covers have pre-cut slits that provide a way for excessive hot air to es- cape. Photo courtesy of Ken-Bar.

- 13. // SEASON EXTENSION TECHNIQUES FOR MARKET GARDENERS PAGE 13 Universities and Foundations Conducting High Tunnel Research (Lamont, 2003) University or Foundation Contact Phone E-mail Pennsylvania State University Center for Plasticulture Bill Lamont 814-865-7118 wlamont@psu.edu http://plasticulture.cas.psu.edu Ohio State University Matt Kleinhenz 330-263-3810 kleinhenz1@osu.edu University of New Hampshire Brent Loy 603-862-3216 jbloy@christa.unh.edu Rutgers University A.J. Both 732-392-9534 both@aesop.rutgers.edu University of Maryland Cooperative Extension Bryan Butler bb113@umail.umd.edu University of Missouri-Columbia Louis Jett 573-884-3287 jettl@missouri.edu Kansas State University Ted Carey 913-438-8762 tcarey@oznet.ksu.edu University of Nebraska Laurie Hodges 402-472-1639 lhodges@unl.edu University of Minnesota Terrance Nennich 218-694-2934 nenni001@umn.edu Michigan State University John Biernbaum 517-353-7728 biernbau@msu.edu Noble Foundation, Oklahoma Steve Upson 580-223-5810 sdupson@noble.org Healthy Farmers Healthy Profits Proj- ect, University of Wisconsin Astrid Newenhouse 608-262-1054 astridn@facstaff.wisc.edu University of Kentucky Brent Rowell 859-257-3374 browell@ca.uky.edu Right: The most critical components of hoop house strength are the end walls. Below: At the Noble Founda- tion, wood end-posts fabricated from two 2- by 6-inch boards, corrugated fiberglass. Photos courtesy of Noble Foundation.

- 14. PAGE 14 //SEASON EXTENSION TECHNIQUES FOR MARKET GARDENERS Several manuals on hoophouses have been pub- lished recently. They give details on construction, crop production, economics, and sources for supplies, equipment, and additional information. Some of these were written by market gardeners who have built and are using hoophouses. Oth- ers were published as a result of research done at universities and private foundations. Titles and ordering information for these are pro- vided under Further Resources. High tunnels have had a tremendous im- pact on season extension. Market garden- ers say the structures pay for themselves in one season. • Crops grown in hoophouses have higher quality and are larger than those grown in the field. • Crops grown in hoophouses can hit the market early when prices are high and help to capture loyal customers for the entire season. • Hoophouses allow certain crops to be grown throughout the winter, pro- viding a continuous supply to markets (and tables) the entire year. Crops that have been grown in high tunnels include specialty cut flowers, lettuce and other greens, carrots, tomatoes, peppers, squash, melons, raspberries, strawberries, blueberries, and cherries. Although high tunnels provide a measure of protection from low temperatures, they are not frost protection systems in the same sense that greenhouses are. On average, tunnels per- mit planting about three weeks earlier than outdoor planting of warm season crops. They also can extend the season for about a month in the fall. Earlier plantings and later harvests would require a supplemental heating system. Location and Site Preparation Alison and Paul Wiediger of Au Naturel Farm in south-central Kentucky grow winter vegetables in 8,500 square feet of high tunnels. In regard to locating a hoophouse, they advise other growers to put it close to the house. Especially on cold days, the shorter the walk from the house to the hoophouse, the more pleasant the trip will be— and the more likely you will be to make it. The Wiedigers advise other growers to prepare the site so that the ground is level from side to side, and has no more than 3% slope from end to end. Avoid wet or shady areas and obstructions to ventilation. Make sure drainage around the site is good. You don’t want water running through the house every time it rains.(Wiediger, 2003) The High Tunnels Web site, www. hightunnels.org, is another valu- able resource. At this site, re- searchers, Extension specialists, professors, students, technicians, and growers are collaborating to share their experience and knowl- edge about the use of high tunnels in the Midwest. Haygrove Tunnel with Cherries. Photo courtesy of Haygrove Tunnels.

- 15. // SEASON EXTENSION TECHNIQUES FOR MARKET GARDENERS PAGE 15 Orientation Dan Nagengast of Wild Onion Farm in eastern Kansas says the orientation (east-west or north- south) depends on your location. Manufacturers recommend orienting the house to capture the most light in winter. For locations north of 40° latitude, the ridge should run east to west. For locations south of 40° latitude, the ridge should run north to south. At any latitude, gutter-con- nected or closely spaced multiple greenhouses will get more light if they are aligned north-south because they avoid the shadow cast by structures to the south.(Byczynski, 2003) Dr. Lewis Jett, in Columbia, Missouri, says that a high tunnel should be oriented perpendicular to prevailing winds: in regard to orientation of a high tunnel, sunlight is less important than ventilation.(Jett, 2004) Design and construction A high tunnel is not difficult to build. The most common design uses galvanized metal bows at- tached to metal posts driven into the ground 4 feet apart—a traditional quonset style structure. Carol A. Miles and Pat Labine in Washington offer construction details for a 10-foot by 42-foot structure that can be built for $350.(Miles and Labine, 1997) See Appendix I. The High Tunnel Production Manual, published by The Pennsylvania State University Center for Plasticulture, details the construction and use of 17- by 36-foot tunnels using a gothic arch de- sign developed by Penn State. (They chose this smaller size for research purposes.) The center section of the end walls can be opened up for easy access by machinery.(Lamont, 2003) Con- struction details only are shown in Appendix II, Design and Construction of the Penn State High Tunnel. The Hoop House Construction Guide, by Steve Up- son of the Noble Foundation, provides details for three designs: quonset, straight wall, and triple side-vent. Upson says the quonset structure is generally the least expensive to purchase. While satisfactory for producing low growing crops, trellised crops can’t be grown close to the sides. Straight wall designs provide unhindered in- ternal access along the sides of the house, while permitting plenty of vertical growing space, but because of the additional pipe required, expect to pay more for materials and to spend more time on construction. The triple side-vent has vents on both ends of the tunnel; one side of the house is taller than the other, and the third vent is at the top of the tall side. This is the most expensive of these three designs. See Further Resources for information. Strength is important. Heavy-gauge galvanized steel pipe is best for hoops. Setting the hoops four feet rather than any further apart is also recommended. Growers in snowy climates might choose a peaked-roof structure instead of the quonset style.(Bartok, 2002) The most critical components of a hoop house for strength are the end walls.(Upson, 2004) At the Noble Founda- tion, wood end-posts fabricated from two 2- by 6-inch boards, corrugated fiberglass panels for end-wall glazing, and industrial steel frame doors with heavy-duty latches, provide long-lasting end walls. The most economical covering is 6-mil green- house grade, UV-treated polyethylene, which should last three to five years. Do not use plastic that is not UV-treated—“It will fall apart after half a season.”(Mattern, 1994) Roll-up sides used on many high tunnels provide a simple and effective way to manage ventilation and control temperature. The edge of the plastic is taped to a one-inch pipe that runs the length of the tunnel. A sliding “T” handle is attached to the end of the pipe so that the plastic can be rolled up as high as the hip board. Ventilation is controlled by rolling up the sides to dispel the heat. Depending on temperature and wind fac- tors, the two sides may be rolled up to different heights. Coleman (1995) gives the following advice for dealing with wind. Wind whipping and abrasion can be a serious prob- lem. No matter how carefully the cover is tightened when it is first put on, it always seems to loosen. There are two ways to deal with this. The simplest is to run stretch cord over the top of the plastic from one side to the other…. One cord between every fourth rib is usually sufficient. The tension of the stretch cord will compensate for the expansion and contraction of the plastic due to temperature change and will keep the cover taut at all times. The sec- ond solution is to cover the tunnel with two layers of plastic and inflate the space between them with a small squirrel cage fan. This creates a taut outer surface that resists wind and helps shed snow.

- 16. PAGE 16 //SEASON EXTENSION TECHNIQUES FOR MARKET GARDENERS Missouri cut flower grower builds a solar-powered hoophouse When Bryan Boeckmann of Westphalia, Missouri, decided to start cultivating cut flowers, a high tunnel seemed like the natural choice. But he had a problem: He couldn’t always be in Westphalia to make the required adjustments. Temperatures in such a structure can easily get too high on a sunny day, and the grower must be on hand to open the vents. “I work full time for the fire department in Jefferson City, and the temperature in a high tunnel can change a lot in a 24-hour period,” he said. “I had to have something I could rely on. Fortunately, necessity is where most good ideas come from.” Boeckmann’s good idea was to use solar power to automatically raise and lower the side curtains on his tunnel. His project was funded by a grant from the Missouri Department of Agriculture. Jim Quinn, the MU extension researcher who helped with the project, said Boeckmann was inspired by existing technology in poultry barns. “He had seen how poultry curtains work, and he thought, ‘Why can’t I do the same thing with a high tunnel and use solar power?’” The curtains are made of white, woven, tarp-like material. They are pulled up to close the sides and lowered to open the sides of the tunnel. Quinn said the innovation “is really a nice fit. The times when you need to adjust the curtains are when there’s a lot of sunny weather, and that’s also when the solar power is available.” Boeckmann initially hoped to drive the side curtains with conventional electric power, but hooking into the grid was “cost-prohibitive,” he said. He called on Missouri Valley Renewable Energy (MOVRE), a firm in Hermann, Missouri, to design and build a solar unit. Using mostly used parts, MOVRE owner Henry Rentz constructed a small building with two solar panels on the roof and an inverter, batteries, and control panel within. “I found some used stuff for Bryan because I wanted him to succeed in what he was doing,” said Rentz. “Those batteries alone would have cost $1,600 new. I basically did it to show people something that already works.” The system succeeded beyond their expectations. “In June, when we had that extended period of rain, that system ran for 11 days without sun, “ Rentz said. “It’s fairly simple, “ Boeckmann said. “Once you’ve initially set it up, typically you don’t have to mess with it. You just have to set the thermostat.” The thermostat in the hoop house senses temperature and, at a set point, triggers a mechanism that very slowly raises or lowers the plastic side curtains. “The reason it moves so slowly is to give the temperature in the building a chance to adjust,” he said. “It takes it 15 minutes to go all the way up. You can do it manually really fast, if a storm is coming.” Boeckmann also uses solar power to drive his irrigation pump—“a little bitty pond pump that doesn’t eat up a lot of juice.” He believes his innovations could boost the already growing interest in high tunnel construction. “There’s good reason for the interest,” he said. “The difference they make is phenomenal, considering it’s just a sheet of plastic stretched over a frame. They just keep improving them.“ For more information, contact Jim Quinn at 573-882-7514 or by e-mail at quinnja@missouri.edu.(Rose, 2004)

- 17. // SEASON EXTENSION TECHNIQUES FOR MARKET GARDENERS PAGE 17 Irrigation is essential for adequate and timely wa- tering. Watering can be done by hand, through a trickle or drip system, or by overhead emitters. The Pennsylvania State Center for Plasticulture High Tunnel Production Manual discusses the advantages of drip irrigation from water being delivered directly to the soil around the crops. • Efficient water and fertilizer use • Reduced weed competition in areas outside the beds • Ability to simultaneously irrigate and work inside tunnels • Reduction in disease potential because water doesn’t get on the leaves If you choose trickle irrigation, use one line per row, or depending on the crop, one line per double row. If the soil is adequately fortified with nutrients, supplemental feeding might not be necessary; however, nitrogen can be applied through the trickle system. The manual also discusses overhead irrigation and provides details on how to construct an over- head system. This allows irrigation water to be applied evenly to the entire soil surface. It can be used to leach salts from tunnel soils or to establish and grow cover crops within the tunnel. A floor covering of a single sheet of 6-mil black plastic or landscape fabric provides several advantages. It warms the soil, controls weeds, greatly reduces evaporation of soil moisture, and serves as a barrier against diseases in the soil that could infect plant parts above ground. Secure the edges (sides and ends) of the plastic to prevent wind from blowing the plastic over the plants. Temperature management using the roll-up sides is critical. On sunny mornings, the sides must be rolled up to prevent a rapid rise in tem- perature. Tomato blossoms, as mentioned earlier, will be damaged when temperatures go above 86°F for a few hours. Even on cloudy days, rolling up the sides provides ventila- tion to help reduce humid- ity that could lead to disease problems. The sides should be rolled down in the evening until night temperatures reach 65°F. A maximum/minimum thermometer is a great aid in keeping tabs on temperature. Twenty feet by 96 feet is a size commonly used by market growers. This size allows ef- ficient heating and cooling, efficient growing space, and adequate natural ventilation. Lynn Byczynski and Dan Nagengast who grow spe- cialty cut flowers and vegetables in Zone 5 near Lawrence, Kansas, have five hoophouses, each 20 by 96 feet. They purchased Polar Cub cold frames from Stuppy Greenhouse Company. They chose Stuppy not because it was the only greenhouse manufacturer, but because it was the closest, so shipping costs were least expensive. The cost for two houses was $3,250, including the metal frames, four-year poly covering, wiggle wire to attach the poly to the frames, and shipping. Lumber to install the roll-up sides and poly-covered endwalls cost an additional $1,600. They also paid a neigh- bor $300 to prepare the site with a bulldozer and laser leveling device. In their first year, the hoophouses produced more than twice what they cost. The record of crops grown, planting and harvest dates, and revenue per square foot is shown in Table 3.(Byczynski, 2003) Additional details, including photos that show the construction of a Stuppy’s Polar Cub cold frame at Wild Onion Farm, can be found in The Hoophouse Manual: Growing Produce and Flowers in Hoophouses and High Tunnels. See Further Resources. Alison and Paul Wiediger also use a commer- cially available 20- by 96-foot high tunnel, in Hoophouses at Wild Onion Farm. Photo courtesy of Wild Onion Farm.

- 18. PAGE 18 //SEASON EXTENSION TECHNIQUES FOR MARKET GARDENERS addition to two 21- by 60-foot tunnels. They think there is value in building as large a structure as is practical.(Wiediger, 2003) Most of the growing in this tunnel will be in spring, fall, and winter when outside temperatures are cooler/colder. We believe that both the earth and the air within the tunnel act as heat sinks when the sun shines. At night, they give up that heat, and keep the plants safe. The smaller the structure, the smaller that temperature “flywheel” is, and the cooler the inside temperatures will be. They also find that plants close to the walls do not grow as well as the plants further from them. The larger the frame, the larger the percentage of effective growing area. And most growers want more, rather than less, space at the end of one growing season. Twenty feet wide, however, may be as wide as you can get with the inexpensive cold frame type hoophouses without interior bracing. Longer than 100 feet or so may be too long for effective natural ventilation. The Wiedigers use a double layer of 6-mil, 4-year poly to cover their tunnels. A small fan blows air between the two layers to create an insulating barrier against the cold. Construction and man- agement details can be found in their manual, Walking to Spring: Using High Tunnels to Grow Produce 52 Weeks a Year. See Further Resources for ordering information. Haygrove Multibay Tunnel Systems With Haygrove tunnels, innovative growers are literally covering their fields to protect high-value crops from early and late frost, heavy rain, wind, hail, and disease. The frames also provide sup- port for shade cloth and bird netting.(DeVault, 2004) The British company Haygrove was started in 1988 with a little more than two acres of straw- berries in hoophouses. By 2002, Haygrove had expanded to nearly 250 acres of soft fruits, includ- Hoophouse production at Wild Onion Farm Crop Date planted Dates of harvest Revenue per square foot Fall-planted flowers Delphinium ‘Clear Springs’ and “Bellamosum” 9/28/00 4/26/01-7/26/01 $2.67 Dianthus (Sweet William) 9/25/00 4/24/01-6/1/01 $5.05 Larkspur ‘Giant Imperial’ 10/7/00 5/2/01 - 6/10/01 $3.25 Spring-planted flowers Stock ‘Cheerful’ 3/21/00 5/18/00-5/30/00 $1.92 Campanual ‘Champion’ 4/1/01 6/3/01-6/30/01 $3.62 Lisianthus 4/12/00 6/26/00-10/8/00 $3.32 Fall-planted vegetables Arugula 9/27/00 fall, spring $1.31 Cilantro 9/27/00 fall, spring $0.95 Chinese cabbage 9/27/00 fall $1.11 Green onions 9/27/00 fall $0.61 Leeks 9/27/00 spring $1.10 Lettuce 9/27/00 fall, spring $0.40 Mizuna 9/27/00 fall $0.69 Spring-planted vegetables Cucumbers 4/12/00 summer $1.34 Tomatoes 4/12/00 summer, fall $3.55 Byczynski, 2003

- 19. // SEASON EXTENSION TECHNIQUES FOR MARKET GARDENERS PAGE 19 ing strawberries, blackberries, red currants, and cherries, grown under plastic in England and eastern Europe. They also came up with a new design for multibay tunnels and sold 3,000 acres of tunnels throughout Europe. Haygrove tunnels are now being distributed and used in the U.S. Haygrove sells tunnels from 18 to 28 feet wide per bay, with a three bay minimum. There are no walls between bays. The total length and width can be whatever the grower desires. Company representative Ralph Cramer in Lancaster Coun- ty, Pennsylvania, says he has seen tunnels as short as 65 feet and as long as 1,100 feet. They have been used to cover from 1/3 acre to 100 acres (of blueberries in California). Unlike greenhouses, Haygrove tunnels don’t need to be built on flat ground, but can be built on slopes. Cramer says advantages of the systems include lower cost and better ventilation.(Cramer, 2004) One acre of Haygrove tunnels costs about 55 cents per square foot, or about $24,000.(Byczynski, 2002) North Carolina market gardeners Alex and Betsy Hitt covered two quarter-acre blocks with Haygroves in 2004. One block was planted to specialty cut flowers, the other to organically grown heirloom tomatoes. Heirlooms have not been bred to resist foliar diseases, and growing organically limits fungicide options. Alex was pleased with the resulting decrease in plant disease: “We have very severe foliar disease Full production in early March at Au Naturel Farm, lettuces and spinach. Photo courtesy of Au Naturel Farm. Haygrove tunnels covering large area. Photo courtesy of Haygrove Tunnels.

- 20. PAGE 20 //SEASON EXTENSION TECHNIQUES FOR MARKET GARDENERS problems on our tomatoes in the field and tradi- tionally would pick a crop for about five weeks, and then it would be dead. With the Haygroves, we picked from the same number of plants for almost 10 weeks and picked and sold 35% more fruit than last year.”(Hitt, 2004) Hitt also noticed less disease in the Haygroves, compared with single bay tunnels with roll-up sides. He attri- butes the difference to better ventilation in the Haygroves, since they vent so high, resulting in less humidity.(Cramer, 2004) Pennsylvania grower Steve Groff of Cedar Mead- ow Farm agrees. In 2004, despite the early arrival of late blight in the eastern United States and Canada, Groff’s six inter-connected bays yielded more than 3,000 25-pound boxes of tomatoes (by October 11), with seventy percent of them grad- ing out at No. 1. His unprotected fields yielded only about 25 to 60 percent percent No. 1s. Groff says 2004 was an extremely unusual year, with a lot of wet weather. Tunnels allowed him to reduce fungicide use by more than 50 percent and allowed tomato harvest to begin two to three weeks earlier. They also extended the season: On October 11, Groff was still picking from tomatoes planted in April, and expected to harvest 100 to 200 more 25-pound boxes. (DeVault, 2004, Groff, 2004) Leitz Farms in Sodus, Michigan, covered 10 acres of tomatoes this year to help control growing conditions. Fred Leitz, one of four brothers who run the family farm, said the plants look healthier than the ones outside and show no sign of dis- ease. Their operation was featured on the front page of Vegetable Growers News.(Morris, 2004) Haygrove tunnels, unlike single bay hoophouses, are not designed to carry a snow load, so they cannot be covered with poly during the winter in areas that have snow. John Berry, director of Haygrove, says “Haygrove tunnels are designed to be temporary low-cost structures that can be moved with the crop. The key management task is venting. Unlike conventional single hoop houses, multibay tunnels can be completely opened to ensure the crop is not stressed by heat or humidity.” Strawberries grown with this sys- tem can be picked two to three weeks earlier in the spring; yields of raspberries, blueberries, and strawberries have consistently been 30 percent higher in tunnels, compared with field grown berries; and the grade-out percentage for soft fruit under the tunnels runs about 90:10 Class A to B, compared with 75:25 for conventional outdoor production.(Otten, 2003) Haygrove tunnel with tomatoes. Photo courtesy Haygrove Tunnels.

- 21. // SEASON EXTENSION TECHNIQUES FOR MARKET GARDENERS PAGE 21 The mobile high tunnel The “salad days” of season extension were argu- ably in the second half of the 19th century, on the outskirts of Paris, where 2,000 or so market gardens employed cloches and cold frames to produce 100,000 tons of out-of-season produce per year. Many of these growers built small trackways on which to move the heavy glass cloches and frames to different parts of the gar- den. (Poisson, 1994) For the past century, Euro- pean horticulturists have put railcar wheels on greenhouses and rolled them on iron rails. The rails extend two or more times the length of the greenhouse, making multiple sites available for one house. Eliot Coleman describes a sample cropping sequence for a mobile greenhouse or high tunnel. An early crop of lettuce is started in the greenhouse on Site 1. When the spring climate is warm enough for the lettuce to finish its growth out-of-doors, the ends are raised and the house is wheeled to Site 2. Early tomato transplants, which need protection at that time of the year, are set out in the greenhouse on Site 2. When summer comes and the tomatoes are safe out-of-doors, the house is rolled to Site 3 to provide tropical conditions during the summer for transplants of exotic melons or greenhouse cucumbers. At the end of the summer, the sequence is reversed. Following the melon and cucumber harvest, the house is returned to Site 2 to protect the tomatoes against fall frosts. Later on, it is moved to Site 1 to cover a late celery crop that was planted after the early lettuce was harvested. Then Site 1 is planted to early lettuce again, and the year begins anew.(Coleman, 1992) Coleman has adapted these practices to his own garden, replacing the heavy and costly iron with more practical wooden rails. He provides plans for his mobile high tunnel, and year-round cropping plans, in his book Four-Season Harvest. See Further Resources. Economics of Season Extension One method for determining whether season extension techniques can be a profitable ad- dition to a farming operation is called partial budgeting.(Ilic, 2004) A partial budget requires assessment of changes in income and expenses that would result from changing to a different practice. It is called a partial budget because it is not necessary to calculate the expenses that would be the same for either practice. Steps to follow in the analysis include: • Decide what crop will be grown using a season extension technique. • Decide what season extension technique will be used. • Calculate costs of the new technique, including supplies, rent or purchase of specialized equipment, labor, water, pest management. Allow for extra hours of labor due to inexperience in the first year. • Calculate the added gross income from the new technique. Gross income is simply the price per unit of produce sold multiplied by the number of units sold. Income changes as a result of a change in the price received per unit, a change in the number of units sold, or both. • Calculate any reduced expenses associated with the change. For example, use of black plastic or paper mulch will reduce the need for cultivation or herbicides. Use of floating row covers will reduce the need for other insect pest management operations. • Add up all the increases and decreases of expense and income and calculate the total change in profit. Specific information on costs of materials and supplies is available from the companies and in the manuals listed under Further Resources. The High Tunnel Production Manual, High-Tun- nel Tomato Production, The Hoophouse Handbook and several Noble Foundation bulletins contain sample budgets for a number of fruits, vegetables, and cut flowers. It must be remembered that any sample budget is just that—a sample. All market gardeners bring their own mix of skills, values, and resources together to build a unique system. According to Coleman(1992): The secret to success in lengthening the season with- out problems or failures is to find the point at which the extent of climate modification is in balance with the extra amount of time, money, and management skill involved in attaining it. When planning for a longer season, remember the farmer’s need for a vacation period during the year. The dark days of December and January, being the most difficult

- 22. PAGE 22 //SEASON EXTENSION TECHNIQUES FOR MARKET GARDENERS months in which to produce crops, are probably worth designating for rest, reorganization, and planning for the new season to come. References Anderson, David F. et al. 1995. Evaluation of a paper mulch made from recycled materials as an alternative to plastic film mulch for vegetables. Journal of Sustainable Agricul- ture. Spring. p. 39–61. Anon. 2002. Making packaging greener: Bio- degradable plastics. Australian Academy of Science. www.science.org.au/nova/061/061key.htm Arnosky, Pamela and Frank. 2004. When frost threatens, know what to expect. Growing for Market. May. p. 15–17. Ashton, Jeff. 1994. A short tale of the long history of season extension. The Natural Farmer. Spring. p. 12–13. Atwood, Sam, and Bill Kelly. 1997. Orchard smudge pots cooked up pall of smog. 3 p. www.aqmd.gov/monthly/smudge.html Bartok, John W. 2004. Shade houses provide seasonal low-cost protected space. Green- house Management & Production. May. p. 56–57. Bartok, John W. 2002. Hoop house designs help ease snow loads. Greenhouse Man- agement & Production. August. p. 75–76. Bergholtz, Peter. 2004. KEN-BAR Products for the Grower: Agricultural plastics. KEN- BAR, Inc., Reading, MA. www.ken-bar.com Byczynski, Lynn. 2002. A cheaper hoophouse? Growing for Market. October. p. 1, 4–7. Bycynski, Lynn (ed.). 2003. The Hoophouse Handbook: Growing Produce and Flowers in Hoophouses and High Tunnels. Fairplain Publications. 60 p. Coleman, Eliot. 1992. The New Organic Grow- er’s Four-Season Harvest. Chelsea Green Publishing, Post Mills, VT. 212 p. Coleman, Eliot. 1995. The New Organic Grow- er: A Master’s Manual of Tools and Tech- niques for the Home and Market Gardener. 2nd Edition. Chelsea Green Publishing, Lebanon, NH. 270 p. Cramer, Ralph. 2004. Personal communica- tion. DeVault, George. 2004. Farming under cover - BIG TIME! The New Farm. August 31. www.newfarm.org/columns/george_devault/ 0804haygrove.shtml Evans, Robert D. 1999. Frost Protection in Orchards and Vineyards. Northern Plains Agricultural Research Laboratory, Sidney, MT. 20 p. www.sidney.ars.usda.gov/ Geisel, Pamela, and Carolyn L. Unruh. 2003. Frost Protection for Citrus and Other Sub- tropicals. University of California Divi- sion of Agriculture and Natural Resources Publication 8100. 4 p. http://anrcatalog.ucdavis.edu Groff, Steve. 2004. Personal communication. Grohsgal, Brett. 2004. Winter crops, part 2: Planting through marketing. Growing for Market. September. p. 9 Guerena, Martín. 2004. Personal communica- tion. Hazzard, Ruth. 1999. Vegetable IPM Message. Vol. 10, No. 1. University of Massachusetts Vegetable & Small Fruit Program. www.umass.edu/umext/programs/agro/veg- smfr/ Articles/Newsletters/pestmessages/may12_ 99.html Hill, David E. 1997. Effects of multiple crop- ping and row covers on specialty melons. Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Sta- tion, New Haven. Bulletin 945. October. 12 p. Hitt, Alex. 2004. Personal communication. Hodges, Laurie, and James R. Brandle. 1996. Windbreaks: An important component in a plasticulture system. HortTechnology. July–September. p. 177–180. Holland Transplanter Co. 2004. Product infor- mation. Holland, MI. www.transplanter.com Ilic, Pedro. 2004. Plastic Tunnels for Early

- 23. // SEASON EXTENSION TECHNIQUES FOR MARKET GARDENERS PAGE 23 Vegetable Production. University of California Small Farm Center Family Farm Series Publications. 21 p. www.sfc.ucdavis.edu/Pubs/Family_Farm_Se- ries/ Jett, Lewis. 2004. High Tunnel Tomato Produc- tion. University of Missouri. 28 p. King, Tim. 2002. Plasticulture without equip- ment. Growing for Market. April. 2002. p. 1, 4–5. Kuack, David. 2003. Dennis DeMatte Jr. on New Jersey’s plastic film recycling pro- gram. Greenhouse Management & Produc- tion. July. p. 90–91. Lamont, William J. 1996. What are the com- ponents of a plasticulture vegetable sys- tem? HortTechnology. July–September. p. 150–154. Lamont, William J., Michael D. Orzolek, E. Jay Holcomb, Kathy Demchek, Eric Burkhart, Lisa White, and Bruce Dye. 2003. Produc- tion system for horticultural crops grown in the Penn State high tunnel. HortTechnol- ogy. April–June. p. 358–362. Lamont, William J., Martin R. McGann, Mi- chael D. Orzolek, Nymbura Mbugua, Bruce Dye, and Dayton Reese. 2002. Design and construction of the Penn State high tunnel. HortTechnology. July–September. p. 447–453. Lamont, WIlliam J. (ed.). 2003.High Tunnel Production Manual. The Pennsylvania State University. 164 p. Long, Cheryl. 1996. New ground: Help spring arrive early. Organic Gardening. April. p. 18–19. Marr, Charles, and William J. Lamont. 1992. Profits, profits, profits: Three reasons to try triple cropping. American Vegetable Grower. February. p. 18, 20. Mattern, Vicki. 1994. Get your earliest toma- toes ever. Organic Gardening. November. p. 26–28, 30, 32. Miles, Carol A., and Pat Labine. 1997. Portable Field Hoophouse. Washington State Uni- versity Cooperative Extension. 7 p. http://cru.cahe.wsu.edu/ Morris, Christine. 2004. Grower erects 10 acres of high tunnels to improve crop quality. American Vegetable Grower. August. p. 1 www.vegetablegrowernews.com/pages/2004/ issue04_08/04_08_Leitz.htm Orzolek, Michael D., and William J. Lamont, Jr. No date. Summary and Recommendations for the Use of Mulch Color in Vegetable Production. The Pennsylvania State Center for Plasticulture. 2 p. www.plasticulture.org Otten, Paul. 2003. High tunnels: Quietly revo- lutionizing high value crops. Northland Berry News. p. 11. Peaceful Valley Farm Supply main catalogue. 2004. Grass Valley, CA. www.groworganic.com Poisson, Leandre and Gretchen. 1994. Solar Gardening: Growing Vegetables Year- Round the American Intensive Way. Chel- sea Green Publishing. 288 p. Rangarajan, Anu, Betsy Ingall, and Mike Davis. Alternative Mulch Products 2003. Cornell University. 4 p. http://www.hort.cornell.edu/extension/com- mercial/vegetables/online/2003veg/PDF/ Mulch2003Final.pdf Rose, Forrest. 2004. Westphalia man builds solar-powered hoophouse. University of Missouri Extension and Ag Information. News release. September 30. Sanders, Douglas. 2001. Using Plastic Mulch and Drip Irrigation for Vegetable Produc- tion. North Carolina State University HIL–33. 6 p. www.ces.ncsu.edu/ Schonbeck, Mark. 1995. Mulching choices for warm-season vegetables. The Virginia Bio- logical Farmer. Spring. p. 16–18. Snyder, Richard L. 2000. Principles of Frost Protection. University of California. 13 p. http://bionet.ucdavis.edu/frostprotection/FP005. htm Thompson, James F., Clay R. Brooks, and Pedro Ilic. 1990. Plastic Tunnel and Mulch Laying Machine. University of California Small Farm Center. Family Farm Series Publications. 4 p.