Indian Farmers' Protest 2020-2021: Using a Food Security Lens to Conduct a Thematic Analysis on Contrasting Media Narratives

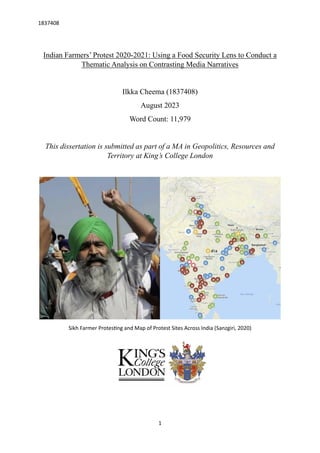

- 1. 1837408 1 Indian Farmers’ Protest 2020-2021: Using a Food Security Lens to Conduct a Thematic Analysis on Contrasting Media Narratives Ilkka Cheema (1837408) August 2023 Word Count: 11,979 This dissertation is submitted as part of a MA in Geopolitics, Resources and Territory at King’s College London Sikh Farmer Protesting and Map of Protest Sites Across India (Sanzgiri, 2020)

- 2. 1837408 2 KING’S COLLEGE LONDON UNIVERSITY OF LONDON DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY MASTERS DISSERTATION I, Ilkka Cheema Hereby declare (a) that this dissertation is my own original work and that all source material used is acknowledged therein; (b) that it has been specially prepared for a degree of King’s College London; and (c) that it does not contain any material that has been or will be submitted to the Examiners of this or any other university, or any material that has been or will be submitted for any other examination. This Dissertation is 11,979 words. Signed Ilkka Cheema Date 29/08/2022

- 3. 1837408 3 Abstract The Indian Farmers’ Protest 2020-2021 is known as the largest protest in human history. Led by farm unions, this mass struggle fought peacefully against the BJP’s implementation of the Farm Law Acts in June 2020. After thirteen months of political resistance involving a sit-in of Delhi’s main motorways, the Modi-led government repealed the Farm Law Acts in December 2021. Using the lens of food security, this dissertation conducts a thematic analysis to critically examine contrasting media coverage of the Indian Farmers Protest. The aim of this dissertation is to uncover the specific media narratives around food security portrayed by the contesting actors in this struggle. As such, the revolutionary newsletter Trolley Times was chosen to analyze the perspectives of the protestors. To contrast it, the mainstream centre- right newspaper, Times of India, was chosen to analyze the establishment perspective driven by the BJP state-corporate nexus. By conducting this research, it becomes possible to extrapolate themes that unpack the motives, incentives and consequences behind both: the implementation of the Farm Law Acts, as well as the political resistance against them by the protestors.

- 4. 1837408 4 Table of Contents Abstract...................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction............................................................................................................................... 5 Relevance of Research............................................................................................................ 7 Research Question.................................................................................................................. 7 Argument................................................................................................................................ 7 Structure of Dissertation .......................................................................................................... Literature Review Food Security and its Dimensions......................................................................................... 11 Indian Agriculture and Neoliberalism................................................................................... 13 West African Social Movements and Protest Logics Framework......................................... 14 Latin American Radical Food Sovereignty ............................................................................ 16 Modi’s Authoritarianism....................................................................................................... 17 Foucault and Bourdieu – Powers of State Theories ............................................................. 17 Modi’s De-Institutionalization of the Media ........................................................................ 19 Research Design and Analysis Methodology ........................................................................................................................ 20 Trolley Times..................................................................................................................... 21 Times of India.................................................................................................................... 22 Data Collection.................................................................................................................. 23 Thematic Analysis ................................................................................................................. 23 Codes................................................................................................................................. 24 Themes.............................................................................................................................. 28 Thematic Maps ................................................................................................................. 29 Discussion of Themes........................................................................................................ 33 Times of India Editorial Analysis ....................................................................................... 40 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….42 References................................................................................................................................ 45 Appendix……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………52 Coded Excerpts ..................................................................................................................... 52 Notes..................................................................................................................................... 76

- 5. 1837408 5 Introduction In 2020, during the Covid-19 pandemic, Indian food security was at the forefront of domestic politics, as Indian farmers engaged in arguably the largest protests ever recorded, capturing global media attention. Protests were focused on Delhi as approximately 1 million farmers, mostly from Punjab, gathered in defiance against the Indian government’s decision to pass three Farm Law Acts through a voice-vote without discussion or consultation under the cover of the Covid-19 emergency (Jodhka, 2021). These three legislative Acts were designed to deregulate the farming sector and open it up to large agribusiness. The big corporates would have newfound freedom to buy, store and decide which crops to produce using contract farming (Jodhka, 2021). The laws removed stockpiling limits while providing the framework for written agreements between farmers and sponsors without mandating them (Narayanan, 2022). The implementation of these laws would eventually end the minimum support price (MSP) regime, making it almost impossible for the local mandis (marketplaces) to survive (Jodhka, 2021). As a result, many farmers would sink further into indebtedness, which is the leading cause for staggeringly high suicide rates among farmers. Ultimately, the main outcome of the laws would be that farmers would lose their lands to corporates, in not immediately, then soon (Jodhka, 2021). Together, these three farm laws were enacted to ‘re-orient the existing regulatory framework of Indian agriculture’ to favour commercial engagement by large domestic and foreign agribusiness. (Jodhka, 2021) Although agriculture contributes only 15% to Indian GDP, around half of the entire Indian workforce is employed in the agrarian sector (Narayanan, 2022). Furthermore, India is a country of smallholders, as approximately 86% of all agricultural operational holdings are less than two hectares (Narayanan, 2022). The protests were organized by 32 farmers unions “Samyukt Kisan Morcha”, mostly based in Punjab, and backed by the ‘All India Kisan Sangharsh Coordination Committee’ (AIKSCC), a platform of 400 farming organizations across the country (Narayanan, 2022). The unprecedented scale and size of the protests brought diverse groups together, including women and different castes such as the Dalits (Narayanan, 2022). The core consensus among the unions remained that the three farm laws needed to be repealed and a price security for crops needed to be re-instated (Narayanan, 2022). Protests were almost all completely peaceful and violence was never encouraged or incited by unions and the organizations. In fact, most of the civilians around the protest sites in Delhi

- 6. 1837408 6 welcomed protestors with a showering of flowers and extended their hospitality for food, water, shelter and clothing (Lalwani, 2021). However, police brutality against protestors occurred frequently at the demonstration sites, as Delhi police tried intimidate and arrest protestors, cut electricity, and barricade protestors off from the centre (Nigham, 2021). Independent media investigations recorded protesters, human rights activists, poets, writers and intellectuals being falsely imprisoned (Narayanan, 2022). Union leaders, journalists, the youth and public figures held the government accountable by broadcasting these events using social media platforms like Twitter and subsequently garnering more support and unity for the protestors (Crowley, 2021). Modi’s government refused to back down and frequently spoke down to farmers, calling them “simple-minded peasants who could not understand the benefits of the new laws, because they were being fooled by vested interests and the opposition parties” (Jodhka, 2021). The government insisted that the three laws had not been explained properly and argued that protestors simply misunderstood what the laws were about. Several rounds of talks resulted in the government offering to suspend the Farm Laws for 18 months to allow for a transition period (Narayanan, 2022). Undeterred, the farmers stayed put and kept protesting for a full repeal. Eventually, after surrounding Delhi and protesting for 13 months, from November 2020 to December 2021, the protestors succeeded in getting the laws repealed through sheer persistence and determination. Prime Minister Modi announced the repeal on November 19, 2021 and on November 29, the three Farm Laws were repealed in parliament via voice vote, without discussion (Narayanan, 2022). However, the farmers did not end the protest out of fear that the government would simply re-instate the laws after the protest sites were cleared and the protestors went home. Furthermore, many demands of the protestors were still pending, including the state guarantee for the MSP, the release of protestors falsely jailed during the protests and the active decentralization of power (Narayanan, 2022). On December 9, 2021, the protestors announced that they would continue the struggle from home since the main objective had been completed and ended the sit-in. On December 11, 2021, the farmers returned home. The extraordinary process of farmers’ political resistance against the Modi regime and the repeal of the three farm laws ended after just over a year. During this period, an estimated 700 farmers died, either trying to get to the protest site or on the protest site itself (Narayanan, 2022).

- 7. 1837408 7 Relevance of Research There is a gap in the scholarly literature, since the 2020 Farmers Protest occurred recently and formally ended just over a year ago. There is a vast mountain of scholarly literature on the evolution of India’s food security strategy and agrarian history. However, there are few peer- reviewed journal articles directly addressing the protests, its origins and its consequences. Furthermore, there are none that attempt a thematic analysis of the media coverage on the farmers protest. The vast media coverage both domestically and internationally clearly influenced the protests, either by amplifying it or by smearing it. This dissertation is filling a gap in the scholarly literature by studying the editorial strategies of Times of India and Trolley Times during the farmers’ protest. This is an exciting opportunity to understand contrasting themes between a globally renowned establishment centre-right newspaper and a revolutionary newsletter from the perspective of the protestors themselves. Research Question The motive that initially guided the research was an interest in understanding how the 2020- 2021 farmers protest evolved as a form of political resistance against the political authoritarianism led by Modi and the BJP government. As such, the lens of food security was chosen to direct the dissertation. Learning about how the protests evolved shifted the research interest towards understanding how particular narratives around food security impacted the portrayal of the farmers protest in the media. Subsequently, the main research question became: How did the two contesting actors of the farmers protest: the protestors and the Modi-led BJP government, utilize power and the media to illustrate differing narratives on food security? Furthermore, what amplification or atrophic effects did Trolley Times and the Times of India have on the evolution of the social movement in the public sphere? Argument By gaining a direct insight into the perspectives of the protestors through Trolley Times, the research drives into the consequences of the neoliberal Farm Law Acts on farmers and understand the motives for farmers, agricultural workers, and more across inter-sectional paradigms of society to engage in a mass struggle. This is coupled with a thorough investigation into the incentives behind the implementation of the Farm Law Acts by Modi and the BJP.

- 8. 1837408 8 The emergence of a key theme early on seemed to guide the battle over control of the media narrative. A ‘fight for survival’ was constantly imagined in both Trolley Times and Times of India. However the intention and meaning differed greatly between the two. In Trolley Times, a the fight was for the survival of livelihoods, people and communities, as well as land, environment and ecology. In contrast, the Times of India media coverage was rooted in the BJP’s fight for the survival of business and the political status quo. This was guided by the BJP’s numerous attempts at blaming opposition parties for the protests, engaging in a partisan struggle for political power which evoked themes of deception and misguidedness on the part of the protestors. Throughout the Times of India media narratives, symbolic power was weaponized by the BJP to label the protestors as ‘Khalistani terrorists’and ‘anti-nationals’. This attempt at de-legitimizing the farmers social movement in the public space by naming the protestors as ‘enemies of the state’ enabled the majoritarian public to be primed for physical violence in retribution. The monopoly on state-sanctioned violence through state- apparatuses like the police and the army allowed the BJP to take a strong-arm approach in the media. Furthermore, BJP propaganda fuelled misinformation attempted to divide protestors. This was countered with accurate and honest accounts of the peaceful protest actions and organizational methods of protestors in Trolley Times. Nevertheless, the protestors realized that the Farm Law Acts represented a miscalculated over-step of BJP statification that could not be validified or guaranteed to the masses. The economic hardship as a consequence of historic neoliberal policies made the Farm Law Acts the final straw that broke the camel’s back. Consequently, the political activism that proliferated across inter-sectional strata in society was bolstered by the symbolic and physical violence and acted to weaken Modi’s authoritarian grip in the public sphere. Furthermore, the unions involving women, youth, landless workers and oppressed groups strengthened the unity of the protests. Coupled with peaceful and positive religious actions, the public support became unwavering and garnered international solidarity. Times of India articles depicted frequent attempts by the BJP to push the benefits of the Farm Law Acts on farmers, explaining that these laws had not been explained properly and that farmers were not well informed enough to understand the benefits they gave. As Trolley Times reported boots-on-the ground coverage of the protests, they portrayed an account that illustrated how well-informed protestors were. They understood the BJP state-corporate nexus that worked to enrich agribusinesses and individuals like Adani and Ambani at the expense of farmers. The

- 9. 1837408 9 incentive for disempowering farmers politically and dispossessing farm land is uncovered by the farmer’s grave accounts of becoming perpetually indebted to pay for seeds, land, and farming equipment. Farmers contested this, using farming unions to amplify their voice as they questioned price-fixing and hoarding that would result from an end to the MSP and the beginning of widespread contractual farming due to the Farm Law Acts. The prioritization of private agribusiness focused on export over small-holder farms was frequently used as a counter-argument by protestors to the BJP’s claims that the Farm Law Acts would benefit farmers. The farmers objectively understood that the three farm law policies were implemented to directly enrich the BJP and agribusiness conglomerates friendly to the party like Adani Group and Reliance, as well as foreign investment, rather than securing the public interest of food security. This portrayal was amplified by Trolley Times. As their coverage progressed, more institutionally credible voices along establishment lines lent their support. Initially Times of India only portrayed accounts that sided with the BJP narrative, but over time this evolved to include various advocates such as farm union leaders, opposition leaders, economists and Delhi residents that countered this claim. By the end of December 2020, Times of India portrayed a more balanced coverage which included national statements by Modi against the protest, as well as counter perspectives in favour of the protest. This was in stark contrast compared to June-October when Times of India amplified BJP viewpoints heavily. An interpreted reason behind the editorial shift is due to the lack of public legitimacy in Modi’s authoritarian tactics that threatened to ruin Times of India’s journalistic credibility if it continued to unevenly back the BJP with unbalanced coverage. Still, the Times of India did not mention the roles of Adani and Ambani, as well as the other large domestic and foreign agribusiness, instead choosing to focus on the liberal struggle. This can be understood as an intentional empty space given the pro-business editorial stance with direct ties to corporates and their own financial incentives to expand the economy through neoliberalization. Structure of dissertation To facilitate a comprehensive thematic analysis of the contrasting media coverage of the farmers protest, this dissertation adopts a methodically robust structure. To begin, the dissertation critically engages with the contemporary literature on food security and its dimensions, as well as heterodox economic literature on how neoliberalism fuelled the agrarian

- 10. 1837408 10 crisis in India. Examples from the developing world are given such as Bolivia and Ecuador. Next, the literature review delves into the theoretical frameworks that guide the thematic analysis. These include Sylla’s protest logics framework derived from West African social movements which enables an analytical understanding of the Indian farmers social movement. Furthermore, the powers of state theories from Foucault and Bourdieu are utilized, underpinning how Modi’s authoritarian strategies of de-institutionalizing the media drove the mainstream media coverage of the farmers protest. This paves the way for a thorough thematic analysis of the contrasting editorial strategies between Times of India and Trolley Times. The methodology section outlines the qualitative approach for extrapolating themes from the two publications in order to critically assess how the portrayal of the farmers protest was built upon differing narratives around Indian food security. This section will include a brief overview of the political leanings of the two news publications and stipulate the method of data collection. This involves describing what data was collected and how the sampling frame for data inclusion was determined. An explanation of the six stages of thematic analysis are provided next, with a focus on how the theoretical frameworks underpin the method, as well as a provision of the assumptions and ethical considerations that went into this analysis from the researcher. The final two chapters in the methodology section guides the reader through the coding process, explaining how codes were generated, categorized and sorted to establish themes. Themes were extrapolated using a deductive approach and the criteria for determining prevalence and the method for interpretation are described. This enables a thematic analysis that critically assesses the underlying ideologies, assumptions and ideas that shaped the contrasting media coverages. Utilizing the theoretical frameworks to delve into the structures and meanings allows an interpretation of themes that informs the argument and answers the research question. The results section illustrates the complex thematic maps which were created. An overall thematic map showcases the connecting themes between the protestors, the Modi/BJP state corporate nexus and the media. Theme maps regarding particularly salient themes are presented. These include the farmers social movement as the fight for survival of food security, livelihoods and land through proletarian struggle, the fight for survival of political stability and business using neoliberal policies and symbolic/physical violence, the strength of unions and intersectional paradigms in the corporatist and liberal struggle, as well as the battle over control of the narrative, influenced by BJP propaganda attempts to divide protestors and countered using accurate boots-on-the ground perspectives from peaceful protestors which swelled public support domestically and internationally. An in-depth discussion of excerpts that demonstrate

- 11. 1837408 11 the contrasting themes are presented with particularly visceral excerpts from Times of India and Trolley Times. The discussion unpicks the motives, incentives and consequences of the Farm Law Acts backed by the BJP state-corporate nexus and the united social movement of the protesting farmers. The discussion ends with a final analysis on how the editorial strategies evolved over time as the protests went on between June and December 2020. The conclusion section summarizes the inextricable link between key themes and their effect on how the two media publications’ differing media strategies to portray the farmers protest revolved around a specific narrative on Indian food security. A final remark on the potential for future protests in India regarding food security concludes the dissertation. Literature Review Food Security and its Dimensions The literature review will begin by broadly defining food security and the variables such as water security that are fundamentally intertwined with it. It is important to define food security within the context of this research. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) uses a definition of food security from the Rome Declaration on World Food Security at the 1996 World Food Summit: “Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life” (FAO, 2008). Food security underpins economic security, which leads to national security and other elements of social security such as health, employment opportunity and education (Narang, 2022). Therefore, the state plays a paramount role in ensuring food security. Food security has four components: Availability, Access, Absorption, and Sustainability. A state achieves these components by institutionalizing laws and policies that mandate food production and distribution (Shrivastava and Kothari, 2014, p.124). Availability refers to the “physical availability of food stocks in desired quantities, which is a function of domestic production, changes in stocks and imports, as well as the distribution of food across territories” (Narang, 2022). Access is determined by people’s physical and economic access to food and the “opportunities open to them to acquire enough food either through their own endeavours or through state intervention or both” (Narang, 2022). A distribution network of food that is

- 12. 1837408 12 affordable and reaches both the masses in the metropolis as well as those few in the remote parts of the country, is essential to achieve food security (Shrivastava and Kothari, 2014, p.124). Absorption is defined as “the ability to biologically utilize the food consumed” (Narang, 2022). Sustainability deals with the idea that environmental sustainability affects food availability and must therefore be a precondition for food security (Narang, 2022). Food insecurity has dimensions that change over time, because it is a dynamic concept (Narang, 2022). A state may be food secure at the moment, but could foresee a potential lack of availability of food in the future. A distinction can also be made between chronic and transitory food insecurity. Chronic food insecurity is used to describe any situation in which people continuously subsist on a meagre diet which has insufficient calories and critical nutrients as prescribed by medical norms (Narang, 2022). On the other hand, a temporary shortage in food availability and consumption is known as transitory food insecurity (Narang, 2022). Food insecurity and water insecurity are inextricably intertwined. If a state is experiencing water security, it is highly likely to experience food insecurity as well, since water is a key component for growing and absorbing food, the agricultural industry and ecological sustainability. In Punjab, over-intensive irrigation has caused water tables to drop at an alarming rate. Subsequently, the World Watch Institute issued a grave warning in 2017: continuing the current rates of ground water extraction, total loss of groundwater will occur in Punjab by 2025! (Baweja et al., 2017). Punjab contributes almost 40% of all rice, 65% of all wheat and 25% of all cotton production in India (Baweja et al., 2017). An exacerbated water insecurity situation undermines the capacity of Punjabi farmers to maintain India’s food security. Nevertheless, according to Narang there are many variables that can accentuate food insecurity, some of which include: food inflation, declining wages, declining rate of growth of agriculture, inappropriate public policies at national and international level (including distribution systems, healthcare provision, education, water supply, sanitation, WB/IMF/WTO negotiations, etc.), negative consequences of globalization on poverty and inequality, non-sustainable development, gender discrimination, violence and militarism, racism and ethnocentrism, age and vulnerability, and so on (Narang, 2022). Many of these variables can be effectively tackled with adequate and inclusive government policy, both at a domestic and international level. This means that, most of the time acute food insecurity is experienced by a population, it is done through a political choice.

- 13. 1837408 13 Food insecurity can be exacerbated by international policy choice to: wage war; prioritize the exportation of cash crops; or implement inflation rate targeting regimes across developing countries. In fact, the Bengal Famine 1942-43, was a result of all three – a brutal colonial policy of engineered price inflation that caused the deaths of three million Indian people (See Appendix British Colonial India and the Bengal Famine). This historical case study can be used to compare the food security linkages and causal mechanisms between the Bengal Famine and the farmers protest in 2020-21. Indian Agriculture and Neoliberalism In the decades after Independence, the Indian state developed an intricate system of food management that utilized state-subsidized foodgrains. Buoyed by increases in the absolute volumes of food production through Green Revolution technologies, India’s distribution network prioritized universal access at affordable prices (Shrivastava and Kothari, 2014). The Food Corporation of India (FCI) purchased foodgrain by offering Minimum Support Prices (MSP) to farmers. Foodgrain was subsequently distributed using the Public Distribution System (PDS) to all urban and rural households with ration cards (Shrivastava and Kothari, 2014). Although there were issues with the quality of grain and corruption, this centralized system ensured foodgrain self-sufficiency, achieved in the 1960s, was coupled with accessibility for the majority (Shrivastava and Kothari, 2014). Under the neoliberal paradigm of free trade, land has been diverted away from producing food grain for local consumption in favour of export crops. Furthermore, food grains have increasingly been exported out of India and used to feed livestock in the Global North (Patnaik, 2009). This has caused rapid food price inflation and is a visible pattern across developing states in the Global South (Patnaik, 2009). By “promoting free trade through IMF and World Bank guided economic reforms, strengthened by the WTO discipline”, advanced economies in the Global North had a clear objective: “to bring about an intensification of the international division of labour in agriculture” (Patnaik, 2009, p.12). Keeping the shelves in Global North supermarkets stocked, has had a large ripple effect. More land has been channeled to meet the Western demand for exotic foods and export crops. This has caused large food deficits within India to occur. To fill these deficits, the IMF and World Bank have mandated economic liberalization for international access to Indian food markets, thus paving the way for India to be ‘supported’ by trans-national corporations who’s profit margins skyrocketed while food

- 14. 1837408 14 security fell. This was coupled with IMF and World Bank conditionalities that stipulated requirements to cut public expenditure by reducing food subsidies (Shrivastava and Kothari, 2015, p.125). As a result of this austerity policy, India experienced a massive spike in malnutrition during the 2000s (Shrivastava and Kothari, 2015, p.125). West African Social Movements and Protest Logics Framework In Liberalism and its Discontents: Social Movements in West Africa, Sylla provides a theoretical framework to analyse protest logics. Sylla defines the ‘social movement’ as “collective protest action targeting a given adversary” (Sylla, 2014, p.31). Within this definition lie three significant elements: 1) “The intentional nature of the collective action; 2) The protest dimension; 3) The identification of an adversary” (Sylla, 2014, p.32). Sylla identifies two methodological approaches to understand social movements: an ‘organisational approach’ and an ‘event-based’ approach, to distinguish between the structured nature of protests by organisations such as trade unions, and sudden or random protests that may be unpredictable (Sylla, 2014, p.33-34). Nevertheless, Sylla reiterates that social movements must be situated within the contexts that they occur and separates varying protests against neoliberalism into five protest logics: 1) Liberal; 2) Republican; 3) Partisan; 4) Corporatist; 5) Proletarian (Sylla, 2014, p.34). These protest logics are summarized in the table below.

- 15. 1837408 15 Protest Logics Table There are four analytical advantages to using these protest logics. First, they allow flexibility as organizations often do not only follow their main protest logic, given that there are intertwining interests such as those between trade unions and proletarian struggles (Sylla, 2014, p.34). In addition, struggles may change over time as, for example, previous principles by republican protests can evolve into partisan struggles. Second, the protest logic reasoning

- 16. 1837408 16 prevents the assumption that there is a complete overlap between those actors that fight for the struggle and the primary beneficiaries of the struggle (Sylla, 2014, p.34). For example, one can fight against discrimination or join a proletarian struggle without being the person being discriminated against or part of the proletariat. Third, problems arising from the ‘legitimacy’ or ‘representativity’ of social movements are resolved by unmasking the motivations behind the struggle, i.e. corporatist and partisan incentives may not spur popular classes to fight (Sylla, 2014, p.34). Lastly, these logics recognize that the potential for social movements to transform society varies: “some of them may fit within the logic of the liberal-capitalist system, while others are more able to overcome it or subvert it” (Sylla, 2014, p.34). Latin American Radical Food Sovereignty Latin America has a strong history of social movements. During the 1990s and 2000s, the ‘Pink Tide’ wave of left-wing revolutions during the 1990s and 2000s, represented a ‘counter- movement against neoliberal globalization’ (Silva, 2009). This shift from neo-extractivist policies towards neo-developmentalism happened in conjunction with radical food sovereignty movements (Clark, 2017). The social movement coalition of farmer’s unions, La Via Campesina, was at the forefront of this revolution (Clark, 2017). In the wake of neoliberalism, they advocated for food sovereignty and state protections in favour of small-holder farmers (Clark, 2017). However, Clark argues that rural development via food sovereignty was not compatible with the neo-developmentalism model (Clark, 2017). Tilzey expands on this, using Bolivia and Ecuador as case studies. The cases of Bolivia and Ecuador under Correa/Moreno and Morales illustrate how protest logics adapt over time and can have consequences that differ from the outcomes that originally guided them. Although proletarian movements in both countries struggled against neo- extractive mechanisms through anti-neoliberal mobilization, they were ultimately co-opted into appeasing the interests of the oligarchy (Tilzey, 2019, p.387). Radical food sovereignty movements that started as proletarian counter-hegemonic protest in the 1990s and 2000s were “progressively assimilated into the national-popular bloc, whilst the hegemonic oligarchy, initially marginalized, saw its influence gradually restored” (Tilzey, 2019, p.387). This transformation process re-legitimized capitalism, utilizing left-leaning populist reform to widen the beneficiaries in the social sphere (Tilzey, 2019, p.387). Especially in Ecuador, the middle- class core of the populist bloc that initially sought to overthrow the hegemony became

- 17. 1837408 17 beneficiaries of higher salaries, fuel subsidies, etc. that subverted the radical food sovereignty movement (Tilzey, 2019, p.387). Consequently, the status quo was restored as the balance of class influence shifted. The capability of counter-hegemonic protest was hampered, while simultaneously strengthening the right-wing extremism of the oligarchy (Tilzey, 2019, p.387). Modi’s Authoritarianism The realpolitik right-wing authoritarianism of the Modi regime fits with this pattern of co- opting class struggles to further solidify the Hindutva ideology and strengthen neoliberal mechanisms. By weaponizing a sense of vulnerability using distorted facts about Partition, the Sikh ‘Khalistan’ movement and anti-Muslim rhetoric, Modi mobilized support by claiming Hindus were second-class citizens in their own country (Jaffrelot, 2022, p.28). Although this is clearly false, the violence towards minorities was an outcome of a perceived social struggle which evolved into national vigilantism, backed by the RSS and supported by the state machinery (Jaffrelot, 2022, p.253). To understand how Modi undermined the state apparatuses and brokered symbolic and real forms of violence, it is necessary to understand the powers of state from a Foucauldian and Bourdieucian lens. Foucault and Bourdieu – Powers of State Theories Foucault viewed the state as a prism that had tangible reach in the minds of people, as well as the bureaucratic field of government practices (Jessen and von Eggers, 2019). Indeed, the state reflects the process of dynamic ‘perpetual statification’, whereby a large iteration of tiny modifications work to “change or shift sources of finance, modes of investment, decision- making centers, forms and types of control, relationships between local powers, the central authority, and so on” (Foucault, 2008, p.77). The power of a state is derived from its ability to appear to society as if it is an object that has an essence (Foucault, 2008). This is achieved through various “governmental practices that refer to it, invoke it and legitimize themselves in relation to it” (Jessen and von Eggers, 2019, p. 65). Sovereign laws are simply a codified representation of state power. In order to protect its territory and uphold security, the state has institutions such as the army, the police and the judicial system at its disposal. These work to ensure the sovereignty of the

- 18. 1837408 18 state and to combat adversaries of the state, whether they are citizens or international actors. These state apparatuses, as well as taxation, keep the population in check (Foucault, 2009, p.247). For Bourdieu, power and the authority of a state derives from its monopoly on legitimate and symbolic violence (Loyal, 2017, p.67). This helps the state succeed in maintaining social order and legitimizes its existence (Bourdieu et al., 1994, p.3). Symbolic violence refers to the “violence which is exercised upon a social agent with his or her complicity” (Bourdieu and Wacquant, 2002, p.167). Symbolic power operates in perpetuating the social order through the state’s ability to name, classify, give meaning, categorize and direct public memory and perception to establish obedience and consensus in the dominated groups of society (Loyal, 2017, p.69). What’s more, they work to disguise the arbitrary character so that the dominated are not aware of it (Loyal, 2017, p.69). Thus, the state is able to generate belief in its legitimacy, whereby the majority obeys its orders without the need for physical coercion. Everyone living under the state’s authority must recognize the state’s point of view which establishes legitimacy. Furthermore, the state checks dissent by making it challenging to voice alternative viewpoints outside the universal ‘common’ sense, thus labelling individuals who do not conform, as outsiders (Loyal, 2017, p.81). This makes it easier for states to accuse and publicly certify outsiders, who do not employ state thinking, as anti-national. Public naming and shaming by the state is immensely powerful and works to designate dissenters as ‘enemies of the state’ who subsequently experience public backlash from the majority. This is made possible through state control over public media. If a state feels that there is enough danger or just cause present, they can subsequently mobilize their monopoly over physical violence to squash dissent. Nevertheless, symbolic forms of power reinforce the state’s authority over the “public powers”, such as state administrations (Loyal, 2017, p.81). Nowhere is this seen more than in the field of parliamentary democracies where politicians who belong to political parties take part in a ‘civil war’, aiming to “mobilize as many agents as possible with the same vision of the social world, and its future, in order to gain power” (Loyal, 2017, p.82).

- 19. 1837408 19 Modi’s De-Institutionalization of the Media Since the Gujarat Riots in 2002, Modi and the BJP have conquered minds with the intention to unite the Hindu Rashtra in opposition to the ‘Other’, i.e. Muslims, Sikhs, Christians or ‘anti- nationals’(Jaffrelot, 2022, p.309). This acted to subvert counter-hegemonic movements such as the protests against the asylum-seeking citizenship laws which discriminated against Muslims, as well as the Farmers Protests. Modi and the BJP have illustrated key indicators of acting as an authoritarian state. They have worked to distort electoral competition, changed the laws and judiciary system to their benefit and used the security apparatus to oppress minorities and repress any opposition (Jaffrelot, 2002, p.254.). Furthermore, they have actively de-institutionalized the fourth pillar of democracy: the media. The Media Ownership Monitor (MOM) reports that most owners of Indian media companies are members or associates of the BJP (Aryal and Bharti, 2021). According to the 2023 World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders, India ranks 161st out of 180 (RSF, 2023). This indicates a high use of censorship, disinformation, bias and propaganda. Additionally, violence against journalists, political activists and intellectuals has contributed to the low score of 36.62, down from 45.33 in 2020 (RSF, 2023). Freedom House defended it’s downgrade of India’s rank, asserting the government used “security, defamation, sedition, hate speech laws and contempt-of-court charges, to curb critical voices in the media” (Jaffrelot, 2022, p.306). Across the media sphere, from local journalists to mainstream news editors, “fear has become all-pervasive”, as the BJP has utilized its symbolic violence and physical violence, including the police, to enforce self-censorship and disinformation tactics (Jaffrelot, 2022, p.303). Private capital has aligned with the state which has caused private media to become the ‘ideological vanguard’ of the state (Jaffrelot, 2022, p.303). The connection between food security and a democratic state with independent media is clear. Any government should have the capacity to prevent food insecurity, especially famine. It is possible for people to escape extreme hunger through government distribution of food at affordable prices and an increase in public employment to give people the ability to buy that food (Sen, 2021) Facing a free press that acts as the watchdog for the public good, it is in the government’s interest to do this (Sen, 2021). The job of the free press is to shine light on the developments of food insecurity, making them known to the entire population (Sen, 2021). Additionally, the present/potential for food insecurity makes it extremely difficult for a

- 20. 1837408 20 government to win elections by democratic vote (Sen, 2021). Therefore, the government has an electoral incentive to tackle food insecurity. However, in an authoritarian regime with a track- record of electoral competition, it becomes easier to gain votes by dividing the population using nationalist-populist rhetoric. Methodology The research design uses a qualitative approach to generating data. This involves the extrapolation of themes from contrasting accounts of the Farmers’ Protest between two forms of media coverage: that of the revolutionary protestors themselves: 1) Trolley Times, a newsletter brought out by like-minded people in support of the protest, and; 2) Times of India, a centre-right mainstream newspaper. Trolley Times was chosen as it represents the unofficial mouthpiece of the protestors. It can be used to analyze the motives, incentives and message around food security from the perspective of the protestors. Times of India was selected to contrast Trolley Times, because it is the largest English newspaper in India that reflects the general consensus of the Indian political elites. This enables analysis from the perspective of the government and the political establishment compared to the protestors. Nevertheless, Times of India was chosen instead of more right-wing publications such as The Hindu Times and Hindustan Times, because those newspapers have become too politically polarized. As they have been co-opted by Hindu nationalist BJP ownership, there is more emphasis on publishing rhetoric rather than facts. Therefore, Times of India was selected to provide a more balanced account with more journalistic and editorial credibility than outright propaganda. Using a thematic analysis, this dissertation will critically assess how the portrayal of the farmers protest differed between the two newspapers. This will allow the reader to see whether the ‘fight for survival’ by Indian farmers concerns, for example, a fight for the survival of livelihoods or if it is a fight for the survival of big agribusiness. By categorizing the themes which the two newspapers portray with their accounts of the farmers protest, it becomes possible to dig into the various incentives, motives, and consequences that the opposing sides of this struggle may have. Furthermore, it allows us to distinguish how their appeal for public support is built around a specific message on food security. The analysis enables researchers to understand how the protests evolved, both on the battlegrounds and in the collective national consciousness of the Indian people, and whether protests may erupt again in the future.

- 21. 1837408 21 Trolley Times The data corpus of this dissertation consists of four editions of Trolley Times containing 60 articles and 53 articles from Times of India. The first data set consists of the first four editions of Trolley Times that appeared bi-weekly between 18th – 31st of December 2020. These were selected, because they are the only editions translated from Punjabi to English. In total, there are 22 editions with the latest one appearing on 9th of December 2022. This coincides with Modi’s repeal of the Farm Law Acts. Although a thorough analysis of all 22 editions would enhance the quality of the thematic analysis, it goes beyond the scope of this research paper to accurately translate the remaining 18 editions. Nevertheless, each edition is four pages and contains contributions from writers, artists, activists and more. Each contribution will be referred to as a data item. The goal of Trolley Times was to circulate protestors’ stories among the 100,000+ protestors camped out at the Delhi borders (Trolley Times ed. 1). The editors’ team were aware of the potential for inaccurate representation based on partisan publishing to cause rifts in the movement and addressed this in the first edition (Trolley Times ed. 1). Therefore, they employed a team to work day and night, choosing stories that saw past such differences in favour of stories that embodied the commitment of the movement. They reasoned that the exemplary nature of unity shown among farmers, labourers, men, women, children, young, old, and across inter-sectional strata of society would guide the editorial choices (Trolley Times ed 1). The main intention for publishing this newsletter was “to clarify the real news in the midst of fake news” (Trolley Times ed 1). The typical format for each edition begins with briefs on the direction and state of the protest, followed by essays, poems, pictures and artworks by contributors (Trolley Times ed 1). The guiding ethos behind the newsletter is to illustrate the hope brought about by the mass political awakening and led by the leaders of the farmers organizations who put pressure on the ruling political party to engage with the people’s welfare (Trolley Times ed 1). Boosted by diaspora-led international recognition, it garnered global attention as global farmers associations and unions such as La Via Campesina expressed their solidarity with the Farmers Protest (La Via Campesina, 2021). Although it remains objective in portraying accurate, boots-on-the-ground events, Trolley Times is by nature a political newsletter. Consequently, Trolley Times unequivocally stated it will post a united front with the Farmers’ movement until victory is achieved (Trolley Times ed 1).

- 22. 1837408 22 Times of India Times of India is the largest English-language newspaper in India, circulating approximately 4 million copies per day and the third largest newspaper circulated across the country (Khanna, 2019; Rakshit, 2023). Times of India has a readership of approximately 17.2 million people, making it the world’s largest selling English newspaper (Rakshit, 2023). It covers all large- scale activities in the country, but is known for its international, national, business and political news (Khanna, 2019). The second data set consists of 53 articles by Times of India. These articles appeared daily and each article consists of a data item. The sampling frame was determined as follows: The articles were selected between June 5, 2020, the day the Three Farm Bills were passed as Ordinances, and December 31st 2020. The end-date matches the sampling frame for the Trolley Times data set to show temporal consistency. By this end-date, it is possible to demonstrate a rigorous thematic analysis that contrasts emerging themes and maps out how the two media coverages evolved over time. Articles were found using the online Times of India archive database. This process involved selecting the year 2020, month: June-December, and day: 1st -31st . For each day, the archive presents a list of all the articles published by the Times of India on that day. Two keyword search terms: ‘Farmer’and ‘Farmers Protest’ were used to filter the articles by content and narrowed the sampling frame down to the research topic. The number of articles regarding ‘farmer’ ranged from approximately 3-5 per day in June, up to 15-20 per day in November- December. The contents of these articles were scanned to assess their salience to the research question. The exclusion criteria was defined as follows: articles that did not relate to the farmers protest social movement, food security factors, grievances by farmers, agricultural business, political editorial stances on agriculture, were not included. The researcher’s discretion was used to determine which articles would be selected based on the keyword search and salience. Times of India journalists wrote the articles and included sources ranging from BJP spokespeople, such as Modi and the BJP farmer’s wing; opposition party spokespeople, industry representatives; businesspeople; spokespeople for farmers unions; political commentators and academics.

- 23. 1837408 23 Data Collection The entire data corpus was initially collected using an Excel spreadsheet. Each data set was allocated to an Excel Sheet. Within each Excel Sheet, columns specified important characteristics regarding each data item, including the online link for the Times of India articles or Edition number for the Trolley Times stories, as well as date, author, location, title, quick notes, and memos. The next section outlines the method of thematic analysis that occurred simultaneously to the data collection and coding processes. Thematic Analysis Braun and Clarke define thematic analysis as “a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data” (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p.79). This dissertation will follow the six-step method for thematic analysis outlined by Braun and Clarke. Their process is built around a recursive method that involves constant moving back and forth across: the entire data set, the coded data excerpts that are analysed, and the final analysis that is produced (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p.86). The first step is familiarizing oneself with the data, reading and re-reading the data sets and jotting down initial notes and ideas (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p.87). Due to the recursive method, writing takes place throughout the entire coding and analysis process. These notes are informed by engagement with the literature before the analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p.87). The second step is generating initial codes. The majority of codes were established before the coding process, however some codes and subcodes were created while the analysis process was ongoing. The coding process involves systematically coding salient excerpts of the data and collating relevant data for each code (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p.87). The third step involves a search for themes. Codes are subsequently collated into potential themes and relevant data regarding each theme is gathered (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p.87). The fourth step is a review of themes. This process requires two levels, first, to check whether themes match the extracted codes, and; second, to generate a thematic analysis ‘map’ (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p.87). The fifth step defines and names the prevalent themes. This is an ongoing process that refines the specific characteristics of each theme and helps build the overarching story of the analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p.87). Each theme must be clearly defined and

- 24. 1837408 24 named to generate a comprehensive and meaningful analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p.87). The last step is producing the final report. Here, vivid and compelling examples of coded extracts are carefully selected to showcase the contrasting themes between Trolley Times and Times of India (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p.87). Following this, a final analysis that relates back to the literature and hypothesis is necessary to answer the research question. In this dissertation, the thematic analysis is based on a ‘contextualist’ method. This method acknowledges the way people extract meaning from their experiences, and, subsequently the way the greater social context affects these meanings (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p.81). As such, the thematic analysis will employ Foucault’s and Bourdieu’s powers of state theories, dependency theory and Sylla’s social movements framework. This enhances the thematic analysis by working to unravel the surface of reality, while simultaneously reflecting the reality (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p.81). For this dissertation, the reality is defined as: the implementation of neoliberal policies and the Farm Law Acts; the real actions of Modi’s use of symbolic and police violence; the stages of protest - the nonviolent tractor march to Delhi, the breaking of police barricades by protestors and the physical sit-in on Delhi’s motorways by protestors. In addition, reality constitutes the real stories penned by protestors in Trolley Times depicting the protest and reasons for it. This reality also includes factual reporting by Times of India. However, the research must carefully consider the accuracy of this reporting, because the impetus for factual reporting is driven and also hindered by the overall BJP agenda for the editorial strategy of Times of India. As such, journalistic bias must be considered. Nevertheless, an ethical consideration on internal biases must also be factored in. This requires pre-conditioned notions by the researcher to be taken into account. The main assumption driving the researchers internal bias rests on the belief that the stories in Trolley Times accurately reflected what was happening on the protest sites. Additionally, the reasons for protest given by the various Trolley Times contributors are accepted as true. Meanwhile, the researcher remains skeptical about the reasons for protest given by the Times of India in their depiction of the protests. The researcher accepts that the Times of India portrayal of government incentives to end the protest may also be compromised.

- 25. 1837408 25 Codes According to Maxwell, the primary purpose of coding is not to count data excerpts, “but to ‘fracture the data and rearrange them into categories,” thus facilitating a contrast or comparison between data excerpts in the same category (Maxwell, 2013, p.107). The process of coding occurred before and during the data collection. While the Excel data collection was ongoing, each data set was simultaneously being collected in NVivo 14 for coding purposes and thematic analysis. This process involved importing each Trolley Times edition and each data item from Times of India onto the software. Next, codes were created in NVivo 14. Codes were generated based on the research question and hypothesis, mapping on to the theoretical frameworks. The recursive nature of generating codes initially and during the analysis process enhanced the quality of research, illustrating development over time with thorough analysis. This dissertation is interested in the way food security issues, Modi’s neoliberal policies and the farmers social movement play out across the data. As such, when coding the data, the focus is particularly on mapping these events with the theoretical frameworks. The outcome is a number of themes around the three nexus categories and theoretical frameworks, which expand on the hypothesis. A preliminary table of codes are summarized below: Initial codes summarized in NVivo 14

- 26. 1837408 26 Codes were categorized as ‘organizational’ or ‘theoretical’. The distinction between these two categories is based on the way in which the data excerpts were sorted. ‘Organizational’ categories are the broad issues or topics that need investigating, identified prior to the analysis (Maxwell, 2013, p.107). These categories function as sorting bins for further analysis (Maxwell, 2013, p.107). The ‘organizational’ categories in this dissertation are the three nexus paradigms: Food Insecurity, Modi/BJP State-Corporate Neoliberalism, and the Farmers’ Social Movement. This category also includes the sub-codes from these main three paradigms. ‘Theoretical’ categories sort the coded data chunks into the theoretical frameworks. In this dissertation, the theoretical categories are the powers of state theories by Foucault and Bourdieu: processes of statification, symbolic/physical violence and Sylla’s protest logics: proletarian-/corporatist-/republican-/liberal-/partisan-struggle. Based on the theoretical categories, the analysis infers an implicit meaning from the coded excerpts. The assigned coding categories were applied to data chunks – excerpts from the data items that demonstrated a feasible connection to the code. These were then triangulated with notes and memos to formulate the map of themes (Maxwell, 2013).

- 27. 1837408 27

- 28. 1837408 28 Themes Themes were extrapolated based on how they reflect the three nexus categories in the hypothesis: Food Insecurity, Modi/BJP State-Corporate Neoliberalism and the Farmers’ Social Movement. This involved a deductive ‘top-down’ approach driven by the theoretical frameworks and coded into theoretical categories (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p.83). The prevalence of themes was determined by assessing how many times a theme was articulated (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p.83). For consistency, this was measured by a majority of instances that a theme was articulated by different actors in the entire data set. This provides a flexible

- 29. 1837408 29 approach to answering the research question. In addition, themes were identified at a latent level of interpretation (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p.84). This meant looking beyond the surface level meanings of the data and beyond what was explicitly written by the protestors and journalists (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p.84). The subsequent analysis assesses the underlying ideologies, assumptions and ideas that shape the content of the data (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p.84). The latent approach is crucial to measure features that give the data chunks and coded excerpts form and meaning (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p.84). As a result, interpretative analysis work goes beyond description and utilizes theoretical frameworks to categorize data chunks into broader themes (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p.84). This makes it possible to find the structures and meanings underpinning both the data and the themes, informing the hypothesis and answering the research question (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p.84). Results Thematic maps Over-arching Thematic Map NVivo 14

- 30. 1837408 30 Thematic map depicting: Farmers’ Protest Social Movement as Proletarian Struggle NVivo14

- 31. 1837408 31 Thematic map depicting the Modi/BJP State-Corporate Nexus & Farm Law Acts NVivo14

- 32. 1837408 32 Discussion of Themes Neoliberal Policy Prioritizing Agribusiness and foreign investment Economic Hardship caused by Farm Laws Food Insecurity arising from Farm Laws The Times of India reports the president of the BJP farmers’ wing saying that the new Farm Acts will not affect farming communities, calling the protestors liars (TNN, 2020). He states that the new law will not affect mandis and regulated markets and that the MSP will stay, while corporates cannot hoard (TNN, 2020). Furthermore, he says the bill will enrich farmers within five years, increasing their livelihoods (TNN, 2020). These sentiments are echoed by Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath and state BJP president Murugan. Although the first Farm Law Act stipulates that farmers are able to sell their produce to anyone without a middleman, Trolley Times argues that this removes responsibility from the government to guarantee the MSP (Kumari, 2020). This means that farmers are not protected when harvests fail and input costs rise. Trolley Times questions how farmers can maintain their livelihoods for the next crop season, especially given that Adani and Ambani corporations can fix prices to protect their interests, regardless of the farmers situation (Kumari, 2020). This will lead to a situation similar to British colonial times as corporates only focus on making profits rather than wellbeing of farmers leaving them to starve (Kumari, 2020). Trolley Times argues that the farm bills promote hoarding as well as price-fixing through contractual farming (Kumari, 2020). This will increase food insecurity especially for farmers and low-income agricultural workers. Within the corporate-state nexus, Adani and Ambani have a clear profit incentive which is achieved by wielding political sway with BJP for favours. This includes selling public sector institutions to Adani and Ambani corporations, providing clear motive. The increasing privatization is an outcome of neoliberal policies that exemplify increasing statification of marketizing, commodifying and liberalizing state- development including agriculture. Additionally, large agribusinesses make larger gains in the corporatist struggle by disempowering farmers unions and reaping massive profits at the expense of farmers. This pattern will continue as shown by previous state institutions that

- 33. 1837408 33 were privatized for the benefit of Ambani and Adani, like airports, ports and telecommunications companies (Kumari, 2020). Ending the use of farmer’s markets will increase food insecurity. As the cap on stockholding of foodgrains is removed, the potential that the FCI will no longer exist increases (Hussein, 2020). Protesting farmers question how prices and supply of foodgrain will be regulated, considering that a universal and timely supply through the PDS is vital to ensure accessibility (Hussein, 2020). A Trolley Times article evokes memories of the Bengal Famine when describing how, despite availability of foodgrains in India, millions died due to private hoarding exporters (Hussein, 2020). However, by 18/12/2020, Times of India published an article explaining how an in-depth report on the flaws of the Farm Law Acts had been submitted to the agriculture minister by academics and economists (TNN, 2020). This change of editorial strategy shows Times of India’s evolution in providing a more balanced account. A Trolley times excerpt provides context for the Farmers’ protest, identifying the Farm Law Acts as the latest process of statification after a history of neoliberalism and failed economic policies such as demonetization (Udasi, 2020). By codifying the law with these Acts, the BJP sought to centralize power, as with demonetization and accelerate the privatization of the agricultural industry. The state passed the Farm Law Acts as Ordinances during Covid, without democratic processes or public oversight. This became a mis-calculated over-stepping of its political capacity. The state could not guarantee the validity of delivering this law into practice as it was heavily criticized by the farmers. By protesting against the Farm Law Acts, the farmers objected the legitimacy of the state to impose laws. Furthermore, as protestors question the BJP’s role in strengthening the state-corporate nexus by disempowering farmers, the state loses credibility, especially in the minds of the public. When dissenters openly reject laws, amid a context of failing welfare and infrastructure, the state’s central power is weakened (Udasi, 2020). This works to strengthen democracy by weakening the authoritarian ruling party and prompting support for opposition parties who gain from people’s discontent. In this partisan struggle, the BJP doubled down on its intention to keep the Farm Law Acts and invoked the rhetoric of security and law and order. The state’s ability to use the army and police gives the ruling power fuel to invoke symbolic violence with the threat of physical violence.

- 34. 1837408 34 Symbolic and Physical Violence Using the media to publicly label the protestors as Khalistanti ‘terrorists’, paid Pakistani ‘anti- national’s and opposition party agitators is a form of symbolic violence (Mishra, 2020). This works to exercise an “unconscious effect of symbolic imposition” to naturalize the official discourse that the movement is illegitimate (Loyal, 2017, p.73). It officially designates the protestors as enemies of the state. A Times of India excerpt illustrates the criticism faced by the BJP for labelling the protesting farmers as ‘enemies of the state’ (TNN, 2020b). The SAD president also criticized the central government’s choice to choke Punjab by not letting trains get through even though protestors had vacated the tracks for a week (TNN, 2020b). Trolley Times exemplifies the protestors’ perspectives of being called anti-national (Singh, 2020). Consequently, this primes the public for physical violence, because the majority has been shown there is just cause to use violence against protestors. This occurred on the march to Delhi as protestors were blockaded and beaten by police (TNN, 2020c). Symbolic violence turns to Physical violence as the full force of police were deployed to deter protestors Proletarian Struggle In the ruling party’s perspective, the use of violence to defend its over-reaching statification processes, strengthens the legitimacy of the state. However, in reality it does the opposite. In the eyes of the people, this gives more just cause to their proletarian struggle and in fact, weakens the legitimacy of the authoritarian state. The ruling party failed to realise the impact the Farm Laws had on the entire proletariat across inter-sectional paradigms. The strength in collective action across religious lines, caste, gender, age, employment, with advocates ranging from doctors to poets, demonstrates how this struggle has united the proletariat on one front. Every worker needs food, especially soldiers. How could a ruling party, who’s nationalist rhetoric has frequently spoken about the dangers of Pakistan and the need for increasing national military security, guarantee that national military security, when most of the armed forces come from farming families. Trolley Times provides an anecdote from a Bapu Ji (grandfather) supportive of the farmers protest who retired from the rank of Subedar after three wars (Sangha, 2020). If even a war veteran who has acted as an arm of the state apparatus with a monopoly on violence and fought three wars for the state, says he will sacrifice his life in this proletarian struggle against

- 35. 1837408 35 the state, the commitment of the entire proletariat cannot be questioned. There can only be one winner when the entire proletariat is ready to sacrifice their lives in this struggle. The state has already lost. Battle over control of the narrative Trolley Times depicts the unwavering public support for the farmers’ social movement, built on love and respect for the protestors (Editorial, 2020). By evoking these strong emotions and attributing them to the feelings of the ‘masses’, Trolley Times is attempting to control the narrative of the protests in favour of the farmers’ movement (Editorial, 2020). This is clearly contrasted by the labels it gives the BJP and corporates, calling them ‘cronies’ and ‘moneybags of the BJP government’ (Editorial, 2020). The Adani and Reliance corporates are engaged in a corporatist struggle. They are clearly incentivized to use of lies and propaganda to falsely advertise the benefits of the Farm Laws to the farmers. Their motive is protecting the material interests of their corporation. Their large conglomerates have reached such massive economies of scale, that they are not in a struggle of pure ‘survival’ in financial or other terms. However, their potential future income revenues are hugely dependent on dispossessing farmers of their land and disempowering them politically, because compounding profits in the future necessitate more and more extraction from farmers in the present. Disempowering them in the political sphere gives farmers little room to object. This motive is unmasked in the battle over control of the narratives around food security. The corporate’s motive is not food security for the masses, because this does not increase their future profit potential. Instead, they use their size, power and reach to lie about the benefits the Farm Laws will have for farmers. Although the farmers know about this devious tactic, the corporates do this in the hope of building support from non-farmers and middle-classes who are not on the frontlines of the struggle. Times of India published BJP appeals for farmers not to be misguided as their dream of turning agriculture into a business of profit will be completed (Sharma, 2020). However, is this truly the dream of farmers or the BJP led corporate-state nexus? In contrast, Trolley Times reports the two-faced nature of Modi who performs lip-service to farmers and Sikhs while simultaneously condemning them (Editorial, 2020). Modi’s words are typical for a populist leader. Using the mainstream media he attempts to control the

- 36. 1837408 36 narrative and smear the protestors. He postures and frames the struggle by farmers and Sikhs as a shared struggle that he embodies. At the same time, he denounces the struggle and utilizes the symbolic violence of ‘naming’ the movement as an instigated ‘conspiracy by the opposition parties’ (ANI, 2020). This is echoed by all of the BJP spokespeople. This primes their audience to feel betrayed by the opposition party, leading to alienation from the opposition party (Rhodes-Purdy et al., 2021, p.1567). This strengthens the identity in the Hindu nationalist culture and labels the movement as an outsider group, thus paving the way to call members of the farmers movement anti-nationals and priming the public for physical violence against them. The symbolic power is also portrayed in the partisan struggle between political parties. Modi has equated Hindutva as the Indian state, therefore any opposition parties that are against it are fought by the BJP in a struggle for the survival of the political status quo. Mainstream Propaganda The republican protest logic stipulates that journalists must act in the public interest to ensure the existing political regime complies with democratic principles (Sylla, 2014). The mainstream media that amplifies the government’s propaganda reinforces symbolic violence and abandons its core duty. It is therefore an illegitimate actor in the republican struggle. Trolley Times reported protestors as saying ‘Down with Lapdog Media’, thereby showing their awareness of the symbolic power wielded by the BJP through mainstream media (Udasi, 2020). They understand the state-corporate nexus very well. Through their struggle, they have raised public awareness of the damaging effect this ruthless quest for capital and power has on farming, lives and livelihoods, with their struggle. Unity across intersectional paradigms After a week of protests, Times of India depicted advocates across the inter-sectional paradigm in an article (Sharma, 2020b). Their report including women farmers, students, doctors and businessmen who came to offer services and spend time at the protest sites amid harsh conditions. However, their focus centred mostly on middle-class elites whereas Trolley

- 37. 1837408 37 Times published stories from advocates across the entire spectrum of intersectionality. Nevertheless, Times of India included a pertinent rhetoric question that criticized the timing, motives and incentives of the government’s decision to pass the Ordinances (Sharma, 2020b): “If the central government was so concerned about Covid spreading, why did it choose this time to enact the laws, that too without consulting us?” Times of India attempts to portray democratic values and detract from its corporate ties with this inclusion, as many readers felt the government’s decision to pass the Laws without a vote or consultation went against their principles of democracy. Religion In Trolley Times, protestors were able to portray the collective unity across religious lines. This is regarded as the greatest strength of the protests (Jasveer, 2020). As voices from Hindus, Sikhs, and Muslims echo the same demands simultaneously, it breaks the BJP’s attempts to divide and smear the protests using religious tensions. Landless Agricultural Workers Trolley Times amplifies the voices of many advocates across inter-sectional paradigms. This excerpt focuses on the president of the Workers Liberation Front who called for landless farm workers to join the struggle (Toor, 2020). This portrayal illustrates the ability of the proletarian struggle to transcend class divisions. The fight for the survival of land and livelihoods affects every class below the ruling classes. Therefore, the strength in unity is demonstrated. Dalits and lower-caste groups Similarly, Dalits and lower-caste groups were inspired by Trolley Times to unite and pursue the workers struggle. A Dalit activist is quoted saying: “If the farm workers unite, then the 35% Dali population of Punjab will also join them” (Toor, 2020). This shows how the nature of the proletarian struggle intersects with the liberal struggle, as discriminated Dalits fight for increasing rights on the back of the farmers social movement. Women Women took centre-stage as advocates for the farmers protest. Women’s involvement is central, as farmers themselves, or as family members of farmers. Furthermore, many women

- 38. 1837408 38 had to take over the farming duties as a result of husband farmer suicides, leading to greater calls by women to support the farmers protest. As president of the BKU Women’s Wing, Harinder Bindu is a prime example of female leadership in the collective union action against the neoliberal Farm Laws (Toor, 2020b). As a veteran of 30 years, she has been on the frontline of the proletarian struggle as a farmer, liberal struggle as a woman and corporatist struggle as a union leader (Toor, 2020b). The protests would not have occurred where it not for the great sacrifices and direct action taken by women to participate in the social movement. Although gender divisions are strong in India with conservative gender roles as the norm, Trolley Times indicated that most, if not all men, were in complete agreement over the participation of women in a united front against a common enemy (Toor, 2020b). Trolley Times reported on the arrival of 1000 protestors at a site in Tikri, of which 450 were women (Toor, 2020a). Meanwhile on the same date, Times of India published a monologue by Modi who said opposition forces were misguiding farmers (TNN, 2020e). There was no article or any mention in Times of India about the addition of 1000 protestors at Tikri. However, there was editorial space for Modi to continue posturing and signaling in the partisan struggle to deflect from protests. Youth Involvement Trolley Times dedicated a headline regarding youth involvement: “Youth will write the story of farmers’ revolution” (Chanot, 2020). The eagerness and ability of the youth to participate in the protests showcased a conscious maturity often missing in mainstream accounts (Sharma, 2020a). The strength and solidarity dispelled rhetoric that they are unaware lazy drug addicts (Chanot, 2020). Providing logistical work, care, security and savvy social media skills to counter BJP attempts at smearing the protest made the youth a vital intersectional paradigm in the struggle (Chanot, 2020). Furthermore, the generation of youth who participated in the protest will always remember their involvement. Writing and sharing stories about their experiences will make sure the younger generations understand the gravity of political protest and influence future protests.