Accounting for Transformative Moments in the History of the Political Cartoon.pdf

- 1. 332 Accounting for Transformative Moments in the History of the Political Cartoon Richard Scully In the ongoing project to construct a global history of the political cartoon (Scully, 2014), one is struck by the need to account for that most basic ofhistorical phenomena: change over time. The cartoon oftoday is very different from that ofa century ago, and even more removed from the artistic forms that existed in previous centuries. So great are these differences, in fact, that although some scholars are happy to treat the Reformation-era woodblock pamphlets, the copper-engraved stand-alone caricatures, the "big cuts" that appeared in weekly periodicals like Punch, and the newspaper-based cartoons ofthe 20th Century, as part ofa continuum (e.g., Coupe, 1986-1993; Dewey, 2007), others are more inclined to treat (e.g.) 18th-Century, stand- alone "caricatures" as being distinct and different from "cartoons." Much ink has been spilt over the shifts in terminology and meaning of descriptors, and the apparent need to refer strictly to "caricature" or "political satire" prior to the application of the word "cartoon" in 1843 (Kunzle, 1973: 2; Paulson, 2007: 312; Bryant, 2009: 7-8; McPhee and Orenstein, 2011: 3-5; Baer, 2012: 217-218). Yet it is encouraging that the great E. H. Gombrich (1963) could refer generally to "cartoons" when discussing a variety ofhistorical forms of the same phenomenon, and W. A. Coupe could happily observe the need for the niceties of classification (1993: xxxiii), but also refer to "cartoons" and "cartoonists" inhabiting the 16th Century (1993: xxxix; 1962: 65-86). The unease one feels when consciously adopting a potentially problematic, teleological perspective -- where all previous forms of visual, political satire are lumped together with the modem political cartoon -- is therefore lessened somewhat when one considers that this is an established practice of the scholarly literature. But it is even more helpful to note that it is in the very transformative changes that can be observed over time -- from distinct art-form to art-form -- that a useful and innovative historical analysis can be based. Historians and art historians are practiced at observing that visual, political satires changed over time, but are rather less practiced at accounting for the reasons for such change. While "emblematical" or "breakthrough" moments (Maidment, 1996: 17), caesuras, and turning- points, have been chronicled, this is merely the historical and art-historical symptom of a much more complex story. What is increasingly emerging in the scholarship of the political cartoon (e.g., Maidment, 2013; Hiley, 2009; Miller, 2009a) is that much deeper analysis is required, and that the transitional and transformative moments that signaled a shift from one form IJOCA, Fall/Winter 2014

- 2. 333 of visual, political satire to another were characterized far more by slow evolution, rather than revolutionary change. In seeking to observe this complexity, it is in recent work by Marc Baer (2012: 244) -- fo_91sing on the context of the political, satirical print in the British parliamentary constituency of Westminster -- that one finds one of the most useful (if preliminary) frameworks for interpreting transformative moments in the history of the political cartoon. Castigating the scholarly tendency to focus on only one or a few exclusive factors in determining shifts in artistic form (and thus joining Maidment and others), Baer identifies seven factors that together interacted to alter the form ofthe cartoon from the stand-alone, satirical print caricature ofthe 18th Century, to the 19th-Century cartoon. These are: 1. Physical (the decline ofcity print-shops and shop window viewing culture). 2. Generational (the passing-away ofkey practitioners). 3. Cultural (new modes ofvisualization, aimed at the high-end market). 4. Social (a transition to private over formerly-public reading cultures; and changed attitudes). 5. Technological (small-run, copper-plate printing giving way to wood, lithography, and steel). 6. Cult ofPersonality (politicians move from being street personalities to "con- structed" personalities). 7. Aesthetics (separation of text and image; a gentler form of satire taking hold). It is possible to extend and modify Baer's list by substituting "socio- economic" for "social" (incorporating the decreasing cost of cartoons as commodities, and their role as status-symbols for an emerging, aspirational middle-class), and imagining "cult ofpersonality" to be more broadly useful if categorized as "political" factors. Also -- and very important if one steps outside the British, or even London-based context, 8. "Legal" factors need to be taken into account. Regimes ofcensorship, as well as self-censorship -- of image as well as of text -- determined and reflected what were deemed to be permissible public statements. Just as new and modified factors may be added to this list, similarly, it is also possible to take Baer's basic model for explaining what was a local, London-based shift from the satirical print to the cartoon, and extend it to each of the distinct "turns" evident across the centuries on a much larger scale. In general, these "turns" can be usefully categorized as "centuries," depending what was the dominant mode of visual, political satire at that historical epoch, thus: The "Long 16th Century"-- "Flysheets" and Pamphlets; The 18th Century-- Stand-Alone Satirical Prints; The 19th Century -- Serio-Comic Weeklies; The 20th Century-- Mass-Circulation Daily Newspapers; and The 21st Century-- Webcomics. IJOCA, Fall/Winter 2014

- 3. 334 Obviously, the lack of a "17th Century" appears problematic, and this is not to say that between the transition from hand-drawn to printed visual, political satire in the 16th Century, and its transformation in the hands of William Hogarth and his contemporaries in the 18th, there was no differentiation in the art-form. Rather, mine is an argument for relative change, in relation to the other major "turns" that are apparent in the development of the cartoon. Across the period in question (roughly the early 1500s to the early 1700s), there was no transformation to compare with that that took place, for example, between the 1880s and 1920s, as the cartoon shifted from being a full-page component ofa satirical weekly periodical, to one ofmuch smaller size, contained within the columns of a daily newspaper. With this in mind, the shape of my Baer-inspired list of factors which -- when they came together at particular historical moments, to transform the political cartoon -- looks like this: • Physical: This factor is best interpreted as one related to place; to the locale in which a cartoon (or its framing media) was created, and where it was circulated. Illustrative of this point is the decline of more local, or city-based circulations (e.g. centered on print-shops, and shop window viewing culture); moves beyond the metropolis towards wider regional or national circulations; mechanisms of international and transnational trade -- including the advent of imperialism and globalization -- which moved cartoons transnationally and globally; and lastly, the move beyond the physical to the virtual, online environment. • Generational: This is not only connected to the passing-away of key, established practitioners (cartoonists, printers, editors, publishers, etc.), but is also bound up with the transition that occurs when new practitioners take their place. There have sometimes been challenges to, or modification of, the status quo by new artists, editors, and other practitioners, who pursued their craft in very different, innovative ways (e.g. the rise of newspaper "press barons" like William Randolph Hearst and Lord Northcliffe at the tum ofthe 20th Century; or, the deliberate rejection of the 19th Century Punch tradition by the likes of David Low in the 20th Century). • Cultural: Baer specifically identified the rise ofnew modes ofvisualization, aimed at the high-end market, as pivotal to his case study. In broader terms, secularization as an ongoing and dynamic process was and has been critical to the very foundations of political cartoon (e.g. Hogarth selecting economic, secular, subjects for his first major forays into the art form). As an extension of Baer's point about the "high end," cycles of "high" and "low" culture, linked to aspiration and class dynamics, have been important. The rise of subversive cultures (particularly, but not exclusively, with regards the 21st Century webcomic), as well as cross-cultural factors (linked to aesthetics) have also been important. • Socio-Economic: Again, to extend Baer's point, shifts from public to private reading cultures have occurred in cycles, with a fascinating, paradoxical phenomenon arising alongside the advent of the Internet (in which reading culture, people are both linked as never before via social media, but isolated at the same time). Changed attitudes among consumers -- the tolerance for crossing a line between good humor and acrimony -- is also cyclical and complex, with boundaries ofprivate versus public being differently defined in IJOCA, Fall/Winter 2014

- 4. different contexts. Social class is also ofabsolute importance when considering the transformational moments in political cartoons and caricature, as numerous studies have shown (Maidment, 2013: 20; Dyrenfurth, 2010; Dyrenfurth and Quartly, 2009; Banta, 2003; Donald, 1996). The cartoon as a commodity and marker of status, attractive to the aspirational middle classes, and one affected by market forces in terms ofcost, must be taken into account. • Technological: Brian Maidment has made it quite clear that any history of prints, political or otherwise, "must include some account ofthe major technical and economic developments of graphic media within a particular historical period," and has rightly criticized the lack of such a focus in the literary, art historical, or other discipline-based studies of satirical art (Maidment, 1996: 14; Maidment, 2013: 6). Although the hand-drawn caricatures of the Italian Renaissance were foundational to the political cartoon, the advent of the printing press -- particularly its proliferation in the period of the Reformation -- was perhaps the greatest transformative moment. Technologies of printing -- including the development of, and then replacement of, copper-plate by lithography and woodblock or steel-engraving; the rise of process and of newsprint, as well as computerized printing -- have shaped the form of the cartoon. Perhaps equivalent to the development of the printing press in terms of potential transformative impact has been the advent of digital media and the Internet. • Political: Baer's observation that politicians and other subjects of political cartoons moved from being street personalities, personally familiar to the masses, to "constructed" personalities or celebrities, less socially-accessible to their constituents, is a useful basis for observing this issue. Cartoonists (just as photographers and paparazzi) have played a role in constructing, as well as demolishing, such personas (Seymour-Ure, 2008), making the politician seem distant and inaccessible, or alternatively, all too humal}.. • Aesthetic: Artistic shifts, both within the genre of the political cartoon, and impacting upon it from without, have played a role in shaping the art form. Readerships and audiences have become more or less fond of certain conventions as taste dictates (e.g. the scatological component of the first two "centuries" discussed here is abhorrent to modem sensibilities), and an initial transition from less text and a clear separation between image and caption in the 19th Century shifting again in the 20th. Smaller editorial -- even "pocket" -- cartoons demanded less text overall, but the influence of comic strips encouraged a return to the speech balloons that had featured in the 18th Century. The rise oflntemet memes now sees the overlay of caption-like text within the space formerly reserved entirely for the image. Simple shifts -- color versus black-and-white-- are also more complex than might otherwise appear, and are linked to technological changes. • Legal: Regimes of censorship, as well as self-censorship, determined and reflected what were deemed to be permissible public statements. One has only to glance at the work of Robert Justin Goldstein (1989a; 1989b; 2000) to see that such factors are of fundamental importance to the form -- even the very existence -- ofpolitical cartoons across a variety of contexts. 335 To a great extent, these apparently discrete factors are inseparable from one another (e.g. where does one draw the line between the cultural expression of socio-economic factors and the process itself? What really separates "political" from "legal" factors?). As such, in what follows, I proceed in a much less schematic fashion, addressing セッュ・エゥュ・ウ@ many or all ( ' ; '·__ IJOC4, Fall/Winter 2014

- 5. 336 of these factors together, and in the order most appropriate for the historical context. They are also listed in no.particular order, except that in which they originally appeared when listed by Baer in his original formulation; I have removed the enumeration to further avoid any sense that the first listed factor --,physical-- is somehow more important than the last-- legal-- factor. Given the immensity of the task in observing how all these factors resulted in change on a global scale, transnationally, across hundreds of national traditions, and several centuries, my emphasis in what follows is Eurocentric and Western. Occasionally, where relevant, I glance across at other essential traditions, but this admittedly limited scope need not be as problematic as it sounds. It has ultimately been the Western (combining a European and Anglo-American) mode that has shaped the political cartoon as a global form (Scully, 2014: 29-47). The "grand tradition of European political caricature" was born in Germany, transmitted via the Netherlands to Britain, and then "reexported to the Continent" (Coupe, 1993: xi-xii). Via mechanisms and processes such as formal and informal imperialism (in particular, the colonization of the New World), the Western form of the art was transmitted from the metropole to the periphery, where it either interacted with pre-existing cultures of visual, political satire -- or prompted the creation of these -- often as a form of resistance to the very pressures of Western encroachment that had introduced the cartoon in the first place. That peripheries then fed-back to the metropole, as well as interacted with one another (independent of the metropole), is another indicator ofjust how dynamic and organic the development ofpolitical cartoons has been. The "Long 16th Century"-- "Flysheets," "Broadsides," and Pamphlets ' In taking a Western- or Eurocentric view of the development of the political cartoon, one is tempted to observe the way ancient and medieval art -- such as Egyptian papyri, Greek vases, Roman graffiti, and Gothic manuscripts -- formed the early bases for the political cartoon in the centuries before it coalesced in recognizable form (McPhee and Orenstein, 2011:5; Bryant, 2009: 8). However, "intriguing as they might be," as Donald Dewey has noted, this tends to smack of "research dreaming after relevance" (Dewey, 2007: 1). What spurred the development of visual, political satire -- as a distinctly modem phenomenon -- was the invention of movable type and the carved woodblock technology that together amounted to "the new mass medium of the printing press" (Coupe, 1993: xi), and the growth of printmaking as a commercial enterprise (McPhee and Orenstein, 2011: 5). W. A. Coupe (1993: xi) has arguedpersuasively for the true origins ofthe visual, political satire known as the cartoon as stemming from Reformation IJOCA, Fall/Winter 2014

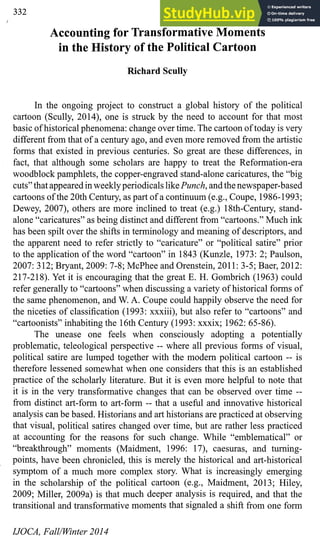

- 6. 337 Germany, and the woodblock "flysheets" and pamphlets that reflected, as well as helped drive the religious reforms of the period. The 15th-Century origins of this phenomenon has been definitively surveyed by Arthur M. Hind (2 vols, 1963a; originally 1935), treating the woodcuts that appeared in books in tandem with the single-sheet and other forms that included, but were not exclusively, satirical in nature. German, Dutch, and other print-makers "seized upon satire as a tool that could throw a cloak of humor over political and religious barbs," but could also advance the cause of the Reformation or Counter-Reformation, depending on their context and market (McPhee and Orenstein, 2011: 5). The "propaganda" ofthe Reformation was certainly religious, but also inherently political in nature (Scribner, 1994). The cross- fertilization that occurred between Germany and the Italian city-states also cannot be discounted, as it was in Renaissance Italy that 'caricatura' (an exaggerated type of portrait drawing) first emerged (McPhee and Orenstein, 2011: 3-5). Fig. 1. Anonymous. "Olever Cromw(!lls cセ「ゥセ・Lエ@ co&tnC•?ll the Trustees of the British Museum. Prints and u「、カゥjエQAsセ@ (c.l649). Courtesy of 1851,0308.560. I fflC'>l!ArfiizllYWinter 2014

- 7. 338 a・ウエィ・エゥ」。ャャケセ@ the woodcuts ofthe period were certainly attuned to other forms ofreligious art, including the illustrations to be found within bibles and prayer books, but also in the stained-glass and other church decorations ofthe age. This was an age when literacy was highly socially stratified (Scribner, 1994: 2), and so people were less attuned to literary conventions than they were to the "complex language ofsaints' emblems andpictorial conversations" (Watt, 1994: 131), and certainly both pamphleteer-caricaturist" and his reader were both privy to the meanings "signified by each emblem and gesture" (Feaver, 1981: 17). Accurate likenesses of real political figures -- successive popes, potentates, and emperors -- are rare within the earlier corpus of"long 16th century" prints, with a three-tiered papal tiara, or iron crown usually sufficient to indicate that the wearer is intended to be a specific individual --such as Pope Clement IV (r.l265-1268), or Konradin (r.1254-1268), the King of Jerusalem and Sicily (Coupe, 1962: 84-85). Later, renderings of an individual's actual (or idealized) features became more common, as in the propagandist Eikon Basi/ike of 1649, depicting England's King Charles I (r.1620-1649) as a martyr (Almack, 1904), or Olever Cromwells Cabinet CouncellDiscoverd(c.1649), which depicts Oliver Cromwell (Lord Protector, 1653-1658) and his colleagues seated at a table alongside a homed Satan (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, it is difficult to identify clear patterns ofcontinuity, as this was a culture which was in a state of constant flux. Images themselves became serious sites and objects of contestation during the Reformation-- when these were denounced by radical Protestants as akin to idolatry (Aston, 1988) -- but as has already been noted, Protestant reformers also utilized them to make major politicaVreligious points, acceptable to and understandable by the masses. This was a new age of images, and so legal novelties also played an important role in shaping the visual, political satires of the period. Aside from the dictates ofprivate and personal morality, the Diet ofWorms (1521) and Peace of Westphalia (1648) established a sustained censorship regime over satirical images in central Europe that endured until the time of the French Revolution (Coupe, 1993: xxii). This kind of censorship was also imposed in heavy-handed fashion in France, with King Charles IX (r.1550- 1574) imposing specific prior censorship on images for the first time in 1561, and this being extended by his successors Henri III (r.1573-1575) in 1581, Louis XIV (r.1643-1715) in 1685, and Louis XV (r.1715-1774) in 1722 (Goldstein, 1989a: 84-87). The Holy Inquisition monitored the status of "heretical drawings" in Spain from 1612, while successive tsars and tsarinas ofAll the Russias enforced bans on personal caricature and regimes of prior censorship of images across the whole period (Goldstein, 1989a: 84-87). In England, too, there was a series of strong statutes and edicts that censored images, especially under the regime of the Star Chamber (1637-1641), the parliamentary Licensing Order (1643) and Oliver Cromwell's prescription IJOCA, Fall/Winter 2014

- 8. 339 of the death penalty for any images that aimed to belittle him personally (1650s). The Civil War in the British realms (1642-1651) did produce some legal space for the polemical manufacturing of "the enemy" (Kunzle, 1973: 125-129), and the Royalist leader Prince Rupert (1619-1682) was notably pilloried in woodblock prints and pamphlets as a witch; his huge poodle, "Boy" was regularly imagined to be his "familiar" (Purkiss, 2001: 276; Stoye, 2011). Likewise, the French Wars ofReligion (1562-1598), the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) in Central Europe, and the wars waged by and against King Louis XIV ofFrance (c.1667-1697), also permitted demonization ofthe enemy in visual satire. But in general, the imposition of censorship of print and of image in the 15th and 16th Centuries was a powerful determinant of the shape ofpolitical cartoons in the whole "long 16th Century." In terms of socio-economic factors that were present at the origins of the political cartoon, the prints and pamphlets ofthis period were "popular" in that they appealed to a wide variety ofpeople from a number ofdifferent class contexts. This is important to consider, as the usual definition of "popular" seeks to distinguish it from "elite" contexts and cultures (Watt, 1994: 2-5). Certainly, "humble" consumers were able to access the cheaper forms of visual, political satire (Watt, 1994: 5), and to some extent this material was also more readily "readable" by those with varying levels of literacy (Watt, 1994: 6-8). This points to the physical spaces ofthe "alehouses," markets, and roadsides as being important spaces for the sale and purchase of such images (Watt, 1994: 6), but churches, theatres, army encampments, and the walls of private residences (Watt, 1994: 178-216) were also sites of dissemination. The importance of the private residence and the church points also to the generational factors that shaped the visual, political satires of the day. Much of the foundational literature -- because of its historical tendency to focus on individual artists and publishers (e.g. Hind, 1963b; originally 1923) -- therefore provides a clear genealogy of cartoonists and their supporting, extended "families" of creators and disseminators. To an extent little studied, the generation that embraced printing -- and that which initiated the Reformation and Counter-Reformation-- needs closer study to determine the importance of this factor for the very creation of the political cartoon. The record will always be incomplete however, as the vast majority ofcartoonists from this period were anonymous, and are still unknown today, justas they were even to scholars ofthe stature of Coupe (1993). The 18th Century Turn -- Stand-alone Satirical Prints In a European context, the first recognizable political cartoon of the early-modern period is usually credited (Atherton, 1974; Press, 1981: 34; Richetti, 2005: 85; Bryant, 2009: 8) to William Hogarth (1697-1764), and IJOCA, Fall/Winter 2014

- 9. 340 his EmblematicalPtint on the South Sea Scheme of 1721 (Fig. 2). Hogarth is more broadly .repre,sentative ofan epoch in comic and satirical art, and David Kunz1e (1973: 297ff.) has gone so far as to characterize the "Hogarthian" inheritance aslasting welLinto the 19th Century; down to Daniel Chodowiecki (1726-1801) in Germany, and Francisco Goya (1746-1828) in Spain. Yet, while Kunzle's investigation of narrative comic art inclines him to see the South Sea Scheme as being old-fashioned, and backward-looking (299), in its own context as a single-frame political satire, it must be seen as novel and forward-looking. Fig. 2. William Hogarth. Emblematical Print on the South Sea Scheme. 1721. In transformative terms, it is the secular theme of the print that is most significant, and which characterizes the 18th-Century "turn" in general. While religious satire certainly persisted well beyond the 18th-Century (something noted in the literary as well as the visual context by Robert A. Kantra, 1984) -- and it is debatable whether the sacred and secular can ever really be treated separately (both being part of the political world) -- it is an increased emphasis on purely secular politics that characterizes the new form ofthe cartoon from the early 1700s. Religious figures are increasingly treated as worldly politicians, rather than representatives of otherworldly concerns; demonization of these and other politicians becomes increasingly figurative, rather than literal. Although this secularization was a process begun much earlier-- something shown by Tessa Watt (1994: 159-168) --it only coalesced IJOCA, Fall/Winter 2014

- 10. 341 with other key factors at this relatively late stage. This is particularly important when one considers that Great Britain in the 1720s was a society not yet free from politico-religious strife: The first Jacobite rebellion (1715) underscored the defensive attitude ofthe Protestant ascendancy, and the fear of Roman Catholicism; a second attempt to restore the Catholic Stuart dynasty in 1745 helped to sustain such concerns. Hogarth himselfwas also very much aware ofthe Dutch tradition ofmoralizing prints, as transnational commercial linkages between England and the Netherlands were still strong, and the legacy ofKing William III (r.1689-1702) --"Dutch William" -- was still felt in Britain (Parramon's, 2003: 14). Thus, there is an unsurprising religious inheritance in all Hogarth's work, drawn from the previous form of satirical print (Paulson, 2007: 299-300) -- with demons and emblematic animals (such as the goat) featuring prominently-- but the South Sea Scheme is definitely a departure. For Hogarth, organized religion tended towards hypocrisy, as well as irrelevance; he showed Protestant, Catholic, and Puritan characters gambling by themselves in the streets at the lower left-hand corner of the print. Their gambling is quite literally a minor issue, separate and irrelevant to the gambling going on en-masse, with the "raffieing," and "lottery" offinancial speculation that is all-too familiar to an observer from the post-2007 world. For Hogarth, the street life of London was pivotal for his development as an artist, and this matches nicely with Baer's emphasis on the physical component of the cartoon's development. As a man in the business of engraving, Hogarth approached his work with a professionalism and attention to his market that allowed him to compete with the high-quality printed work imported from Germany and the Netherlands (Petersen, 2011: 44). He benefited from developments in printing efficiency (Kidson, 1999), but also legal factors. The lapsing ofparliament's Licensing Order and the Licensing of the Press Act (1695) provided printmakers with far greater freedom (although this was tempered somewhat by the imposition of the Stamp Act from 1712, taxing printed productions). Hogarth also benefited from the first legal protections granted to artists and authors: the Statute of Anne (1710), which was effectively the beginning of copyright law in Britain (Petersen, 2011: 44). It was Hogarth who helped drive the campaign to extend the statute to cover printed imagery, something that was achieved in 1735 with the passage of the Engraving Copyright Act (Cornish, 2010: 22; Petersen, 2011: 44). Hogarth's efforts were inspirational to many ofhis generation and those who followed, but in many ways, it was not Hogarth but his successors who really transformed the political cartoon. Hogarth turned quickly towards social satire, and was only "mildly political" (Press, 1981: 34; Upton, 2006). It was later, "in about 1750," among that aristocratic class ofEnglishmen who travelledto Italy onregular"GrandTours" --andwere thus exposedto genuine, IJOCA, Fall/Winter 2014

- 11. 342 Italian caricatura --that Hogarth's symbolic print was merged with the "new art ofcaricaturing" (Gombrich, 1963: 135). Significantly, George Townshend (1724-1807) took to caricaturing his fellow aristocrats, government ministers, and most famously (after being dispatched to North America to fight the French) his commanding officer, James Wolfe (1727-1759) (Paulson, 2007: 312; Desbarats and Mosher, 1979: 21-23). At this early stage, therefore, the political cartoon was transmitted from its British metropolitan context to that ofNorth America by the sharp edge of imperialism; just as the "softer edge" of the Anglo-American print culture saw the first American political cartoon produced by Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) in woodcut: "Join, or Die," of 1754 (Dewey, 2007: 2). Townshend's images of actual people and political figures -- rather than emblematic Hogarthian "types" -- were picked-up by etchers and printer-sellers in London -- notably Henry Bunbury (1750-1811) --and laid the foundation for Thomas Rowlandson (1756-1827) and James Gillray (1756-1815), who finalized the transition to the political caricature and satirical print by the 1780s (Paulson, 2007: 312). While David Kunzle (1973: 358) describes the advent of caricature as a "revolution," in reality -- as I've suggested here -- it was a transition much more evolutionary in nature. However, Kunzle is correct in terms ofthe final factor that characterized this transformation: the move from engraving to etching. The slow and laborious process of engraving was "relatively rigid" when compared with the freer, "swiftly flowing and spontaneous" process and product of etching (Kunzle, 1963: 358). The very process by which such images were created certainly "encouraged the elaboration of detail" (Hiley, 2009: 26). A copper printing plate was prepared with a thin wax or varnish coating, onto which the cartoonist himself would transfer his preliminary sketch, and then use an etching needle to cut through the coating and down to the copper (Hiley, 2009: 26). Image and text were worked on at the same time, with the plate then being immersed in an acid substance that would eat away at the exposed sections copper, creating the grooves into which the ink would collect for the printing stage (Hill, 1967: 6-8). Teams of people then entered into the production process, with wood presses operated by the publisher (and usually, also the owner of the print shop), turning out several hundred copies in only a few days, and then hand-coloring being undertaken by other staff(Hiley, 2009: 26; Hill, 1967: 8). In terms of the socio-economic aspects of the transformation, there exists significant debate over precisely how "popular" this new form of visual, political satire actually was (Maidment, 2013: 120). At a shilling each (or half a crown if colored), these were expensive items to purchase, and therefore beyond the reach of many people, and were "simply too expensive to circulate freely" (Hiley, 2009: 26). Although accessible to more people via their regular display in city print shop windows (as emphasized in Diana Donald's work, 1996; reiterated in Baer, 2012: 222) -- and therefore IJOCA, Fall/Winter 2014

- 12. 343 transformative in terms ofthe physical place, and space they occupied -- it is important to emphasize the still-limited readership for such cartoons, largely confined as it was to a knowing political class of people that varied from context to context. In London, these were not "the multitudes" implied by Linda Colley's use of such cartoons as drivers of a new British nationalism (Colley, 1992: 210), but a much more elite group. While Marc Baer (2012) emphasizes the exceptional size ofthe electorate in Westminster-- and thus a greater circulation for the prints created and disseminated there -- in broader terms, these were still for the (albeit expanding) upper-middle class, and the "wealthy" (Hiley, 2009: 26). Fig. 3. James Gillray. The French Invasion; or, John Bull Bombarding the Bum-Boats. Lon- don: H. Humphrey. 1793. That the vulgarities and grotesqueries of Gillray-style caricature (e.g. The French Invasion, Fig. 3) would have been appealing to this social IJOCA, Fall/Winter 2014

- 13. 344 milieu is also indicative of a cultural and aesthetic transition towards greater secularization, which Hogarth may have begun, but which evolved far beyond his original moralizing intent. This was enduring, and arose surprisingly early in the century, with the anonymous 1740 print Idol-Worship, or, the Way to Preferment famously depicting an ambitious member of the political classes kissing the Prime Minister-- Robert Walpole (1676-1745) --on the posterior. A product of the "peculiar alliance of radicalism and aristocratic party rivalries of the Georgian age" (Kunzle, 1983: 346), this was something that would change dramatically in the next transformative phase in the history of the political cartoon, in the Victorian period. The 19th Century Turn -- Serio-Comic Weeklies Just as the transformational period that created the satirical print -- or political caricature -- was an extended one, so too there was a "long period of transition between two very different eras ofgraphic humor, the Georgian and the Victorian" (Kunzle, 1983: 339). David Kunzle dates this period from between the death ofGillray (1815) and the advent ofPunch (1841), but Brian Maidment prefers to postdate it slightly (1820-1850), to the period "when single-plate political caricature was beginning to disperse into more socially oriented, more diffuse, smaller comic images aimed at a broader range of consumers" (Kunzle, 1983: 339; Maidment, 2013: 116 and 3ff.). Regardless of the precise periodization, as is well-established in the literature, "in this period caricature was gradually and erratically domesticated in tone, format, and content": It was transformed from the sharply personal and political to the broadly and decorously social; from the independent, irregular, and often violently scurrilous political broadsheet to magazine and serial illustration of regular periodicity, often subservient to a text and beholden to an editorial policy and mass taste not ofthe caricaturist's choosing (Kunzle, 1983: 339). Following Baer's analysis ofthe factors resulting in change (2012: 218) -- which was ofcourse formulated with this very period oftransition in mind -- it is plain that the shift was in part due to a drop-offin the number ofvisual, political satires, a greater consensus in terms of their ideological content (rather than, as Baer would have it, a decline in ideological "charge" overall), and a greatly expanded audience for the form. At this time, there developed a new culture "of reading and looking -- casual, momentary amusement, a few seconds chuckle at the fireside or in the stagecoach, or, later, in a railway carriage; harmless fun suited also (and this is very important) to children" (Kunzle, 1983: 339). It need hardly be stated that this immediacy was something very different from the "relatively IJOCA, Fall/Winter 2014

- 14. 345 prolonged attention demanded by a Hogarth plate or caricature broadsheet of old" (Kunzle, 1983: 339). The new culture of reading also tended towards more private practice, than the public, print-shop viewing of the previous century (Baer, 2012: 221) That the cartoon of the 19th Century was inferior to the political caricatures of the 18th has become a commonplace of the scholarship. Certainly, the cartoon became more "domesticated, conservative, and diluted for a 'polite' audience" (Taws, 2010: 34), but to introduce condescending artistic criticism is adopt a too-narrow view. Again, it is to privilege a few factors above all others, thus failing to appreciate -- as Henry Miller (2009a: esp.275-282) has to such admirable effect -- the significance of change in an historical context. Although he is arguably just as guilty of such value- judgments as other scholars, Kunzle has noted a broader context: "this [socio-economic and cultural] pattern of development was underpinned by a political shift," as "a new audience erupted from below, capable of voicing and echoing political demands" (Kunzle, 1983: 339). Yet, although this was a middle-class, "middlebrow" audience (Maidment, 2013: 3) --whose members may have flirted with radicalism as a means of advancing their own version ofcivil society -- increasingly, their watchword was respectability, in contrast to Georgian vulgarity (Gatrell, 2006: 415-595). The middle classes which had purchased caricatures and prints -- and thus bought into the aristocratic culture of vulgarity in the 18th Century -- had changed their aesthetic and cultural tastes, and this coincided with the moment of its rapid expansion in demographic terms (Steinbach, 2012: 118). In generational terms, Kunzle (1983: 339) and others identify the career of George Cruikshank (1792-1878) as characteristic of this transition. The "modem Gillray" (Jackson and Tomkins, 2011: 39) was taught to draw and etch by his father -- the famous caricaturists Isaac Cruikshank (1762-1811) -- and so was very much a product of the 18th Century tradition (Feaver, 1981: 62). Yet despite initially continuing in his father's footsteps, George underwent what can only be described as a generational shift. After a last hurrah as a commentator on the inertia of government as well as the villainy of radicalism (c.1819-1821) and of the Prince Regent (later King George IV, r.1820-1830), he himself became conservative as he aged, and consequently "softened, dispersed and regularized" his work (Kunzle, 1983: 339) as the new, Victorian sensibilities took hold. Cartoonists simply had "more to lose" ifthey "sinned against the values ofthe time" (Miller, 2009a: 268). Even at a time ofpolitical reform-- the context for the Great ReformAct (1832) and its successor (1867), in Britain -- strident radicalism was dimmed in comparison to the "gentle, socially dominant satires" ofJohn Doyle (1797- 1868), who became famous under the pseudonym "HB" (Taws, 2010: 34). Doyle's method was still the stand-alone satirical print, but his monthly issues bore little resemblance to the workof Rowlandson, Gillray, or early IJOCA, Fall/Winter 2014

- 15. 346 Cruikshank. The reasons for this change were not merely socio-economic, or aesthetic, but also technological. From 1827, Doyle and his publisher Thomas McLean (1788-1875) utilized the new technology of lithography to produce "crayon-like effects," derived from the unique textures and "pastel colors" made possible by the medium (Maidment, 1996: 16). Therefore, "the tamer genius ofH.B." (Robertson, 1838: 291) must be appreciated in technological terms, as much as with regards other factors. However, it was not in Britain that lithography became the dominant means of production for cartoons, but rather in France, where a new generation of caricaturists benefited from the relative liberalization of the press laws in the wake ofthe 1830 revolution (Goldstein, 1989b: 120ff.). This also occurred later, in Germany, where it was largely due to the "rapidity and relative cheapness of the lithographic process that made possible the flood of caricatures that accompanied the Revolution of 1848" (Coupe, 1993: xii). The most important nexus of the 18th- and 19th-Century form of the cartoon was arguably one publisher-- Maison Aubert, Paris-- and its major publications: La Caricature (a "high-end satirical publication"), and Le Charivari (a cheaper daily edition) (Cuno, 1983: 350-352). La Caricature was essentially a collection oflithograph prints, designed to be disassembled and the constituent prints framed or otherwise displayed as prints had always -been (McPhee and Orenstein, 2011: 14-15). Le Charivari was similar, but also contained satirical text as well. Although Maison Aubert did have its rivals -- the print shop of Aaron Martinet (1762-1841) being the most prominent -- it was the focal point for the work of both Charles Philipon (1800-1861) and Honore Daumier (1808-1879), the twin geniuses of French caricature (McPhee and Orenstein, 2011 : 12-15). Less restricted than their Victorian British cousins in terms of propriety and respectability, for many observers, it is Philipon and Daumier who inherited the mantle ofGillray and Rowlandson (McPhee and Orenstein, 2011: 6). These men inspired the heroic age of French cartooning, ridiculing Louis Philippe, King of the French (r.1830-1848) as a pear, taking advantage ofthe freedom to criticize under the Second Republic (1848-1852), and continuing the struggle even after Louis Napoleon (or Napoleon III, Emperor ofthe French, 1852-1870) imposed the heaviest and most calculated censorship regime ever faced by cartoonists for almost the duration ofhis long reign (Scully, 2011: 147-180). The global, transformative importance ofthe French school is inherently bound-up with Le Charivari's self-proclaimed, British-based imitator: The London Charivari, otherwise known as Punch (1841-1992; 1996-2002). Punch was the culmination of several years of experimentation, as British publishers struggled to imitate the French example and establish a viable serio-comic periodical. An early attempt was made in Scotland, with William Heath's Glasgow Looking Glass (1825) and Northern Looking Glass (1825- 1826), but the dynamism of London as a metropolitan center proved that it IJOCA, Fall/Winter 2014

- 16. 347 would take the lead in this regard; Thomas McClean's Looking Glass (1830) is an indicator of this (Maidment, 2009: 95, 251). Figaro in London (1831- 1839) --featuring the talents of Robert Seymour (1798-1836) --and Punch in London (1832) prefigured the London Charivari (Spielmann, 1895a: 654-666; Burnand, 1903: 96-105), as was first explored by its semi-official historian Marion H. Spielmann (1858-1948) and its longstanding editor, Sir F. C. Burnand (1836-1917). Originally quite radical in its approach -- and possessing a "cultural nostalgia" for the Regency period which belies its status as the epitome ofVictorianism (Maidment, 2013: 210 and 214) -- Punch became milder over time, as it "donned the dress-coat" (Spielmann, 1895b: 4) and adopted a deliberate policy of appealing and speaking to the middle-ground and the middle-class (Altick, 1997: 11; Leary, 2010: esp.39- 56, 110-132). Fig 4. John Leech. "Cartoon, No.1 -- Substance and Shadow." Punch; or, the London Charivari. July 15, 1843: 23. As is now well-known, it was the impeccably "respectable" John Leech (1817-1864) who first applied the term "cartoon" to a satirical image with a political message (Miller, 2009a). "Cartoon No.1 -- Substance and Shadow" (Punch, 1843: 23 -- Fig. 4) was not the first recognizable cartoon to appear in Punch, but was the first to be so described, and it was a name that stuck. Leech's cartoons-- and those of his immediate predecessors, and long-term successors -- were not lithographs, but rather an improved form of the woodblock print, which had been the original basis for the cartoon in the "long 16th Century." Leech and other cartoonists of the day drew their work directly onto the face ofa whitened wooden printing block (Hiley, 2009: 28), which was then sent away for engraving and printing. This single block was ' /JOCA, Fall/Winter 20/4

- 17. 348 actually made up ofa number ofcubed sections, which -- when the cartoonist had finished -- were given to a number of wood engravers, in order to speed up the process (Hiley, 2009: 28). The need for speedy turnaround was not only related to there being only a few days between an editorial decision being made and the regular publishing deadline -- something the occasional and ad-hoc prints of the 18th Century did not have to contend with -- but also because wood engraving was still -- as it was in the "long 16th Century" -- extremely painstaking and laborious: the white areas of the woodblock needed to be cut away, leaving only the raised lines left by the cartoonist (a Beckett, 1903: 164). Once completed, the block could be combined with text to form a given page ofthat periodical's number (Hiley, 2009: 28). Patrick Leary (2010: 35) has noted how the full-page cartoon may have drawn on the stand-alone satirical print for inspiration, but it also "hastened that genre's demise": the market for the Hogarth-, Gillray-, or even Doyle- style of print had entirely evaporated by the 1840s, partly because readers could purchase entire issues of magazines filled with cartoons, for a fraction of the price of an old-fashioned, stand-alone print. Punch was only 3d. per issue, while some of its competitors were priced even more cheaply (Hiley, 2009: 28), once the "taxes on knowledge" were repealed in the 1860s (Miller, 2009a: 277). There were survivals (Baer, 2012: 224), and indeed, the cartoons within magazines like Punch and Judy were certainly designed so that they might be removed and displayed in much the same way as stand-alone prints from the previous era (Scully, 2013: 451, 455-456). Poster art and postcards (McDonald, 1993: 5-9) filled the gap left by the broadsheet print, and as has been inferred by quite a few studies ofthe "golden age" ofposter art (James, 2009: 4; Aulich and Hewitt, 2007: 107), and of cartoons as well (Bryant, 2006), the political poster was essentially an outgrowth and maturation of the full-page political cartoon. But the transition was a definitive one, with caricature prints going out of fashion by the 1840s. By way of a further generational comment -- in addition to the earlier reference to Cruikshank -- it is significant that the sons of the famous John "H.B." Doyle -- Richard (1824-1883), Henry (1827-1892), and Charles (1832-1893) --pursued not the stand-alone print, but the cartoons ofPunch as their chosen medium. Under the likes of Richard Doyle, but especially Leech and his colleague and successor, Sir John Tenniel (1820-1914), the Punch form of the serio-comic weekly -- and the cartoons they contained -- would become dominant in Britain, spawning imitators such as Fun (1861-1901), Judy (1867-1907), The Tomahawk (1867-1870), and Moonshine (1879-1902) in metropolitan London; Toby (1884-1885), Liverpool Lion (1847-1848), and The Dart (1876-1911) in regional England; MacPunch (1868-1869) and Bailie (1872-1926) in Scotland; Zozimus (1870-1872) and Zoz (1876-1879) in Ireland, andYPunch Cymraeg (1858-1864) in Wales (Miller, 2009b: 285- 302). Such periodical-borne cartoons also spread both to continental Europe IJOCA, Fall/Winter 2014

- 18. 349 and beyond, to the rest ofthe world (Scully, 2013b; Cross, 2006). Punch-like papers proliferated in the formal and informal British Empire, while other serio-comic periodicals -- such as the St. Louis- and then New York-based Puck (1871-1918) -- came via the circuitous route of European periodicals inspired by Punch. Unlike 18th-Century caricatures, "cartoons rarely provided spatial contexts for their exaggerated characters" (Baer, 202: 221), and this both reflected the decline ofspecific, physical factors that influenced their creation and dissemination, as well as permitted their wider circulation, into the national and transnational contexts described above. Political cartoons were increasingly set in imagined contexts, rather than in the identifiable streets or houses of a given context; the employment of imagined theatrical or pantomime contexts for events on the figurative "world stage" -- used by Tenniel, but also his rival Matt Morgan (1837-1890) --is a good example of this (Scully, 2011: 370-372). The 20th Century Turn-- Mass-circulation Daily Newspapers Despite being responsible for actually bestowing the very name by which the "cartoon" has since come to be known, the 19th Century form of the cartoon appears to have been the shortest-lived of all. Having only established itself in the 1840s, already by the 1880s and 1890s, advances of the same physical, generational, cultural, social, technological, and other nature that had led to its creation, meant that a newer form was emerging to usurp its dominance. This was inherently bound-up with the advent of "new" journalism. The Hungarian-born publisher Joseph Pulitzer (1847- 1911), and his great rival William Randolph Hearst (1863-1951) were critical to the emergence both of this new form of print mass media, as well as to shaping the role ofthe cartoon in the new context. It was Pulitzer who hired the cartoonist Walter Hugh McDougall (1858-1938) to produce illustrations for his New York-based daily paper The World in 1884. McDougall's "The Royal Feast of Belshazzar Blaine and the Money Kings" (Oct. 30, 1884: 1 -- Fig. 5) "created a sensation" when it appeared on the front page of The World, just a few days before the presidential election (Hess and Northrop, 2013: 68). Reproduced in huge quantities by an effective Democratic political machine, the cartoon has been credited with ensuring that the Republican, James G. Blaine, lost in New York (by fewer than 1,100 votes), thus losing the presidency to his Democratic opponent, Grover Cleveland (President, 1885-1889 and 1893-1897) (Hess and Northrop, 2013: 70). With the validity ofthe newspaper-based cartoon proven, it was Hearst's poaching of Richard Outcault (1863-1928), and his signature creation-- the "Yellow Dugan Kid" --from Pulitzer, that gave the new journalism its alternative name: "yellow IJOCA, Fall/Winter 2014

- 19. 350 Fig. 5. Walter Hugh McDougall. "The Royal Feast of Belshazzar Blaine and the Money Kings." The World. Oct. 30, 1884: 1. journalism" (Campbell, 2001: 32-33). Pulitzer's use ofthe cartoon was part ofa broader strategy ofappealing to a mass audience. Initially skeptical about hiring full-time artists, he soon came round to the idea once it became clear that circulation figures increased along with the amount of illustrative material (Brown, 2006: 235). "Eye-catching graphics," including illustrations, comics, and cartoons, were designed to appeal to the working classes and those less proficient with the heavy text-based papers ofthe time (Hess and Northrop, 2013: 70). Pulitzer's approach was soon copied by Hearst, first at the San Francisco Examiner - which he was given by his father in 1887 -- and then in the New York Journal, which he purchased for $180,000 in 1895 (Hess and Northrop, 2013: 70). With the latter paper, he launched an all-out circulation war with Pulitzer on his home turf ofNew York, in which cartoons played a major role. Across the Atlantic, similar patterns were emerging in Britain, particularly within the growing newspaper empire of W. T. Stead (1849- 1912), and that of Alfred Harmsworth (1865-1922) and his brother Harold (1868-1940). Unsurprisingly, the brothers Harmsworth cut their teeth on the dedicated comic book Comic Cuts (founded 1890), the first issue of which was little more than an "amalgam of reprints from American magazine" (British Comics, n.d.). Following Harmsworth's purchase of The Evening News (1894), and the foundation of The Daily Mail (1896), the failure ofthe IJOCA, Fall/Winter 2014

- 20. 351 Daily Mirror (founded 1903) prompted Harmsworth to pursue more radical means to ensure success, and his appointment of Arkas Sapt (1874-1923) to rescue the Mirror was critical. When the freelance cartoonist William Kerridge Haselden (1872-1953) approached Harmsworth for a job, he was referred to Sapt, who saw in the daily political cartoons a means ofincreasing circulation (BCA, n.d.). On a starting salary of £5 per week, Haselden soon rivaled the cartoonist who had been the first ever appointed to the staff of a daily newspaper (Hiley, 2009: 32), Sir Francis Carruthers Gould (1844-1925). Gould had joined the Pall Mall Budget (the weekly edition of the Pall Mall Gazette) in 1887, recruited by the crusading "apostle of New Journalism" W. T. Stead (Bryant, 2011: 583). Stead was deeply interested in cartoons and caricatures, and would eventually run a regular feature in his trans-Atlantic (and indeed, global) Review of Reviews from 1890, notably featuring an interview and appraisal of Gould in a 1903 edition (Stead, 1903: 20-29). But it took until after Stead's departure to found Review ofReviews for Gould to be made a permanent staff-member of the daily Gazette; Stead's successor E. T. Cook (1857-1919) invited him to join in 1889 (Bryant, 2011: 583- 584). Gould endured a punishing schedule, entirely new in terms of British cartooning. Unlike the men ofPunch, Gould had only hours, rather than days, to complete his cartoons (Bryant, 2011: 584-585), and this was something that also characterized his time at the Westminster Gazette, where he moved in 1892, following the Pall Mall Gazette's purchase by an unsympathetic American businessman -- and future Tory aristocrat -- William WaldorfAstor (1848-1919). In terms of technology, the move away from wood-block printing and towards "process" was also a major factor in the transformation ofthe cartoon. Although invented in France around the 1850s, "process" -- or zincography -- only entered widespread use in Britain in the early 1890s, and involved the photographic transfer of an original drawing onto a metal plate, which was then treated and etched so that the lines were in relief (Morris, 2005: 116; Hiley, 2009: 30). Laborious block-work was now becoming a thing of the past, and even in cases where process was applied to the existing woodblock technology (as at Punch), the more time-consuming methods of the 19th Century were superseded (Morris, 2005: 116). This became essential to the rapid turnaround demanded of cartoonists working to a daily newspaper schedule, as men like Haselden had their work swiftly transferred to process plates, molded, and set with text, to be printed on enormous, industrial printing presses that utilized drum-shaped rollers and huge reels of cheap, thin, wood-pulp paper (Hiley, 2009: 33, 30). Gould's punishing schedule of five cartoons per week for ten months of the year (Bryant, 2011: 584-585; Bryant and Heneage, 1994: 94) would have been impossible without the cheaper, faster process of reproduction. IJOCA, Fall/Winter 2014

- 21. 352 These shifts were also generational. Hearst was a young up-and- comer when he intervened in newspaper publishing; cartoonists raised on the Puck and Punch tradition struggled to adjust to the less elaborate, more "grinding, daily demand" of the newspaper, and this led to the hiring ofnew blood (Hess and Northrop, 2013: 73). In Britain, the departure of William Boucher from Judy (1888), and John Gordon Thomson from Fun (1893), left the editors of those magazines searching for effective replacements at a time when these were difficult to find (Scully, 2013a: 456). Readerships, too, were undergoing significant generational change, as the education reforms in the United States (compulsory schooling being instituted in all states between 1852 and 1917) and the United Kingdom (Gladstone's Education Act of 1870 being pivotal), produced ever-larger, more-literate, newspaper- reading populations (Graham, 1974: esp.5; Hale, 1940: vi-vii). Engagement with political issues also increased with the new generations, for while voting had been a right in the democratic United States since independence, and the Australasian colonies also benefited from democratic government from an early date, it took successive Reform Acts in Britain (1867, 1884, 1918), the democratization ofthe political process in France under the Third Republic (1870-1940), and a more organic growth of middle- and working- class engagement in Germany during the last years ofthe Kaiserreich (1871- 1918), to create truly politically-interested societies. Relaxed censorship mechanisms in Western Europe also played a significant role (Goldstein, 1989a: 101-112), as an extension of shifts in political engagement. It is not beyond the realms of possibility that political cartoons played a significant, didactic role in the increased political engagement ofthe period. The quite sudden appearance of political cartoons in daily newspapers "struck a mortal blow at the satirical journal as a purveyor of political comment" (Coupe, 1993: xviii), or at least dealt "a hard body blow to the magazines" (Dewey, 2007: 35), from which they seemed unable to recover. The most talented cartoonists were now in much greater demand, could command higher incomes, and obtain much greater visibility, and were lured away from the likes of Puck, Judge, and Harpers Weekly. One such star -- Frederick Burr Opper (1857-1937) -- was persuaded to come over from Puck to join Hearst's New York Journal in 1899 (Hess and Northrop, 2013: 72). There is not a little irony, however, in that}t was the serio-comic periodicals which helped the process along, thus helping to seal the fate of the 19th Century form of the cartoon: McDougall himself had been hired by Pulitzer only after having had his "Belshazzar" rejected by Puck. In Australia, the Melbourne Punch made a deliberate move towards reportage ofsocial gossip, effectively abdicating much ofits former political focus, and this was taken up enthusiastically by newspapers (Fabian, 1982: 2). This was also broadly true in Britain, where one commentator noted that by 1897, "[m] agazine publishers were abandoning political controversy in their search for IJOCA, Fall/Winter 2014

- 22. 353 increased circulation" (Hiley, 2009: 33). In aesthetic terms, the impact of the multi-panel comic cannot be overstated as a transformative element in the news century. Itself a form that was derived from the same genealogy as I have been following above, its parallel development now fed -back into the very genre that had helped create it. Nicholas Hiley (2009: 29-31) points to the emergence of the comic "Ally Sloper" as pivotal to the transformation ofthe cartoon in Britain, and Dewey (2007: 41) makes a similarpoint in terms ofthe "funnies" in the United States. W. K. Haselden moved to multi-frame format relatively quickly following his appointment to the Daily Mirror, but tended to move away from political matters; at least until the Great War erupted, prompting him to examine the "Sad Experience ofBig and Little Willie" -- Kaiser Wilhelm II and the Crown Prince of Germany (BCA, n.d.). Although it is easy to see this period of the 1880s to the 1920s as a revolutionary one, again just as was the case at the tum of the 19th Century, any change was delayed, and the revolution was at best incomplete. The ultimate form of the daily newspaper cartoon -- the "pocket" cartoon appearing on front pages -- did not come into its own until as late as 1939, with the pioneering work of Osbert Lancaster (1908-1986) at the Daily Express (BCA, n.d.). Much earlier, in the US, Puck's greatest cartoonist -- Bernhard Gillam (1856-1896) -- defected not to one of the new mass- circulation dailies, but to a rival serio-comic periodical, Judge (Dewey, 2007: 35). Having only been founded in 1881, Judge continued to thrive into the 1920s (and survived into the 1940s); while Puck survived into the period of the Great War, being bought by Hearst in 1916, and publishing many of the cartoons of Louis Raemaekers (1869-1956) before folding in 1918 (Scully, 2014b: 36). Life arrived in 1883 when John Ames Mitchell and Andrew Miller "temporarily heated up the weekly market"; Frank Leslie s Illustrated Newspaper and Harpers Weekly declined, but also continued to be published until 1922 and 1916, respectively (Dewey, 2007: 36; Brown, 2006: 234; Mott, 1967: 469-487). In Australia, The Bulletin survived and thrived in the new era of the newspaper cartoon (although it certainly became more conservative in the same period), while the Melbourne Punch continued until 1925 (Scully, 2013c: 536). In Britain, Punch still reigned supreme as a venue for weekly political commentary, utilizing the same technologies, editorial practices, and accessing the same social and cultural milieu as it had over the preceding decades; in 1901 Sir John Tenniel was succeeded by Linley Samboume (1844-1910) as chief cartoonist, and he in tum by Sir Bernard Partridge (1861-1945), who maintained the Victorian Punch tradition well into the 1940s (Morris, 2005: 986-995; Ormond, 2010: 251-302; Low, 1956: 90, 208-211; Huggett, 1981: 121). On the European continent, the serio- comic weekly survived and thrived much longer, especially in the French context (Gardes, Houdre and Poirier, 2011). IJOCA, Fall/Winter 2014

- 23. 354 In seeking for a clear "end-point" for the 20th Century "tum," the most useful signifier ofthe new form and status ofthe political cartoon is the almost simultaneous institutional recognition of editorial cartoonists as being of great import. In the United States, the appropriately-themed Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning was instituted in 1922. In Australia, in 1924, the Society ofAustralian Black and White Artists -- the first professional association of cartoonists in the world -- put the cartoonist on a sound institutional footing, and one that has inspired numerous similar associations in the succeeding decades (Scully, 2013c: 534-535). The 21st Century Turn-- Webcomics It is difficult to conceptualise the transformative impact of the Internet without being put in mind of the original, revolutionary context provided by the printing press at the tum of the "long 16th Century." This is reflected in the transformative impact of that super-medium on the political cartoon, for while computer-generated imagery has been around since at least the 1980s, it was not until the advent of the Internet that a definable, new medium for cartoons arrived. In technical terms, the early 1990s was the critical moment, with Tim Bemers-Lee (ca.l993/1994) having built all the necessary working tools and software for a functioning "world wide web" by late 1990, and the Internet expanding in the years thereafter. The Internet then advanced beyond an entirely text-based medium with the introduction of Mosaic's graphic user interface (GUI) 1993, which enabled the inclusion of both scanned images (drawn by hand using traditional media and then uploaded in electronic format) and/or computer-generated images (drawn in dedicated computer programs) (Campbell, 2006: 14-15; Hicks, 2009: 11.2). The rapid take-up of the Internet in the 1990s and the 2000s, has vastly increased the potential readership of web comics, and "broadened the landscape in which it is possible to situate text and image combined in the form of the comic in order to make social, political and cultural commentary while entertaining and engaging the reader" (Hicks, 2009: 11.1). The decrease in the expense offlatbed scanners and other devices, as well as the improvement in drawing and photo-editing software over time, has made both means of creating and disseminating webcomics more prevalent. To some extent, this has papered- over the continuing "digital divide" in terms of cartoonists' IT skills, and enabled print-based cartoonists to remain effective in communicating their work and ideas. Progressively, however, webcomics are more and more likely to have been created entirely electronically, with no "original" hard- copy ever having been created. This is partly a generational issue, as those who became established as cartoonists before the advent of the Internet (or before the widespread IJOCA, Fall/Winter 2014

- 24. 355 take-up ofpersonal IT), have continued to work in traditional media. Without wishing to generalize (IT take-up by older users is far more widespread than it is often assumed), the generation that has grown up since the early 1990s, and which, with its "extraordinary technological aprtitude" (Paglia, 2004: 2) is categorized as being "native" to the web, has produced a crop ofnew artists often working exclusively with IT. Unlike their predecessors, many of these web cartoonists are freer to express their views in a relatively uncensored space, which is inexpensive and open to experimentation and activism in ways that the newsprint media was (and is) not (Hicks, 2009: 11.2). There is a corollary to this, which is often greater difficulty in disseminating their work and raising their profiles, but several initiatives and collectives have developed in order to counter the problem (Rall, 2006). Precisely who qualifies as a "cartoonist" is now also much more of an open question than ever before. At this transformational moment in the history of the genre, virtually anyone -- provided they have access to a personal computer, the ability to manage the software for their purpose, and access to the Internet -- can become a cartoonist. While "true" webcomics (entirely original works, owing more in terms of style and structure to the historical forms of the cartoon) are more difficult to produce, the advent of Internet "memes" (original works based heavily on existing imagery, and dependent for their impact upon widespread knowledge of the original, or at least the format) allow people with a point to prove the opportunity to plug text into an existing image. There is a difficulty in categorizing such works so strictly as "true webcomics" or "memes." Although in the Internet age, technical terminology and jargon abounds -- serving the same purposes as jargon has always served (including obfuscation and the protection of privileged knowledge from widespread understanding) -- the power of individual users and online communities to develop their own langw1ges is unparalleled. Terms like "cartoonist" -- and therefore "cartoon" -- are now no longer within the power of established, professional bodies (or academics) to define. The role of cartoonist, and the forms that cartoons can take, are therefore now much less defined than in the past. As noted above, without any significant artistic skill, a web user can become a cartoonist, and make a useful contribution to political satire, simply by employing the technology at her or his disposal. Take, for instance, this anonymous Russian webcomic from c.2011 (Fig.6): Through extremely crude, but effective means, the cartoonist has taken a World War II poster of Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin (1878-1953) and replaced his visage with the current (and seemingly eternal) President ofthe Russian Federation, Vladimir Putin (b.l952). Indeed, the very crudity of the alterations play a role in the effectiveness ofthe piece, enhancing the feel that this is vandalism for political purposes, just as one would tag or otherwise IJOCA, Fall/Winter 2014

- 25. 356 deface a real poster, or public space, for effect. It is worth noting that the meaning of this webcomic is potentially ambivalent, as a western viewer would immediately make the negative connection between tyranny and the continued rule of Putin in Russia, but viewed from a Russian perspective -- Fig. 6. Anonymous. "Glory to the Great Stalin! Glory to the Great Putin!" c.2011. Fig. 7. Anonymous. "And Then I Said." c.2006. in which Stalin is being progressively rehabilitated as a great man of history (by no less a person than Putin himself) -- there is potentially far more being said than might otherwise be apparent. The same is true of other forms of comment or humor in webcomic form. Although more usually .employed for pure entertainment and humor, some memes ofrecent years certainly possess political overtones, either in the image utilized, or the text embedded. The "Reagan White House Laughing Meme" (otherwise known as "And Then I IJOCA, Fall/Winter 2014

- 26. 357 Said"-- Fig. 7) is an example of this (knowyourmeme, n.d.). Ryan North's webcomic Dinosaur Comics is another example of pre-existing art that can be appropriated for whatever purpose the user desires, and some political cartoons have emerged as a result (Hicks, 2009: 11.4-11.5). Just as in previous epochs, the rise of a new form of media is only part of the story of the cartoon's evolution. Without taking into account the decline of its previous dominant medium -- in this case the newspaper -- one can only know part of the story, particularly as there is considerable debate over whether the editorial cartoon need also be considered "in decline" (Danjoux, 2007). As long ago as 2005, the latter-day press baron, Rupert Murdoch (b.1931), was forecasting a gloomy future for the newspaper, given the likelihood that revenues from classified advertising would "dry up" as online and new media take an ever-increasing share ofpeople's economic and information-gathering time and effort (Plunkett, 2005). Just a few years later, Paul Gillin founded his Newspaper Death Watch blog, seeking to chronicle the decline and extinction of the old structures of print journalism, and he has not been short of material in the subsequent seven year period. While the "death" of the newspaper is actually quite an old-fashioned notion (first being posited in the early 20th Century), by 2009 Marianne Hicks was able to state quite unequivocally: "the newspaper no longer wields the social reach and political potency it commanded in earlier times" (Hicks, 2009: 11.1). In 2014, it is now a truism that newsprint is on the way out, and yet the recent trend towards "freesheets" and away from paid-for newspapers, indicates that reports ofthe newspaper's death have been at least partially exaggerated (Manson, n.d.). In many ways, therefore, we are in 2014 still in a transitional period between cartoon art forms, just as in the early 18th Century, the secular satirical print in the manner ofHogarth coexisted alongside its predecessors; the satirical print continued to be vital even once serio-comic periodicals had introduced the new form of the "cartoon" as late as the 1840s; and the "large cut" cartoon had not yet given way entirely to the newspaper-based cartoon in the early 20th Century. As the Russian webcomic indicates, the geographical "digital divide" ofonly a few years ago-- with the vast majority of online engagement occurring in the West (and the vast majority of that occurring in a North American context)-- is lessening, although it still exists (Hicks, 2009: 11.3-11.4). Just as the forces of imperialism and globalization transmitted the Western form of the political cartoon to other comic art contexts, so too the largely Western technology, and associated cultures, of the Internet are making their way out from the metropole to the periphery. However, the open-ended nature of this current transformative moment in the history of visual, political satire presents the intriguing possibility that this moment will be far less dominated by British, European, or American forms of the art, as well as generational, political, culture, socio-economic, /- I:JOCA, Fall/Winter 2014 I

- 27. 358 and other factors dealt with throughout this article (see, Luedecke, 2009; Kim Ki Hong, 2012). Indeed, the Internet has the power to annihilate the physical, and transfer the development of the political cartoon entirely to the virtual, space (despite art works being housed physically as data in hard- drives, on servers, etc.). This account of the five transformative moments in the history ofthe political cartoon has also been one which is very masculine, and so just as the 21st Century tum may prove to be less Eurocentric -- or Western -- once it is completed, it may indeed be something in which gender balances are much more equal than in the past. At the risk of pre-empting developments (something an historian should never presume to do), it seems that "at least in its digital form," the future ofthe political cartoon "has never seemed brighter" (Danjoux, 2007: 247). References aBeckett, Arthur William. 1903. The aBeckett sof "Punch": Memories of Father and Sons. New York: E. P. Dutton. Almack, Edward, ed. 1904. Eikon Basi/ike; or, The Kings Book. London: A. Moring, Ltd. Altick, Richard D. 1997. Punch: the Lively Youth of a British Institution, 1841-1851. Colm11bus, OH: Ohio State University Press. Aston, Margaret. 1988. Englands Iconoclasts-- Volume I: Laws against Im- ages. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Atherton, Herbert M. 1974. Political Prints in the Age ofHogarth: A Study ofthe Ideographical Representations ofPolitics. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Aulich, Jim and John Hewitt. 2007. Seduction or Instruction? First World War Posters in Britain and Europe. Manchester: Manchester Uni- versity Press. Baer, Marc. 2012. The Rise andFall ofRadical Westminster, 1780-1890. Bas- ingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Banta, Martha. 2003. Barbaric Intercourse: Caricature and the Culture of Conduct, 1841-1936. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. BCA [British Cartoon Archive]. n.d. "William Kerridge Haselden." Available at <http://www.cartoons.ac.uk/artists/william-kerridgehaseldenlbi- ography>. Accessed March 6, 2014. BCA [British Cartoon Archive] n.d. "Osbert Lancaster." Available at <http:// www.cartoons.ac.uk/artists/osbertlancaster/biography>. Accessed March 14, 2014. Bemers-Lee, Tim. ca.1993/1994. "A Brief History of the Web." World Wide Web Consortium. Available at <http://www.w3.org/Designlssues/ TimBook-old/History.html>. Accessed March 4, 2014. IJOCA, Fall/Winter 2014

- 28. 359 BM [British Museum]. n.d. Olever.Cromwells Cabinet Councell Discoverd (c.l649). Available at <http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/col- lection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?assetid=576620and- objectid=3067386andpartid=l>. Accessed March 13, 2014. British Comics. n.d. "Comic Cuts." Available at <http://www.britishcomics. com/Comic Cuts/index.htm>. Accessed March 6, 2014. Brown, Joshua. 2006. Beyond the Lines: Pictorial Reporting, Everyday Life, and the Crisis ofGildedAge America. Berkeley: University of Cal- ifornia Press. Bryant, Mark. 2006. World War I in Cartoons. London: Grub Street. Bryant, Mark. 2009. Napoleonic Wars in Cartoons. London: Grub Street. Bryant, Mark. 2011. "Vinegar Not Vitriol: The Picture-Politics of Sir Fran- cis Carruthers Gould (1844-1925)." International Journal ofComic Art. 13(2, Fall): 583-585. Bryant, Mark and Simon Heneage, eds. 1994. Dictionary ofBritish Cartoon- ists and Caricaturists, 1730-1980. Aldershot: Scolar. Burnand, F. C. 1903. "'Mr. Punch.' Some Precursors and Competitors." Pall Mall Magazine. 29: 96-105. Campbell, T. 2006. A History ofWebcomics v1.0. San Antonio, TX: Antarctic Press. Campbell, Joseph W. 2001. Yellow Journalism: Puncturing the Myths, Defin- ing the Legacies. Westport, CT: Praeger. Cornish, William. 2010. "The Statute of Anne 1709-10: Its Historical Set- ting." In Global Copyright: Three Hundred Years Since the Statute ofAnne, from 1709 to Cyberspace, edited by Lionel Bently, Uma Suthersanen, and Paul Torremans, pp. 14-25. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. Coupe, W. A. 1962. "Political and Religious Cartoons of the Thirty Years' War." Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 25( 1/2, Jan.-June): 65-86. Coupe, W. A. 1993. German Political Satires from the Reformation to the Second World War. Part I-- 1500-1848. Commentary. White Plains, NY: Kraus International Publications. Cross, Anthony. 2006. "The Crimean War and the Caricature War." The Sla- vonic and East European Review. 84(3): 460-480. Cuno, James. 1983. "Charles Philipon, La Maison Aubert, and the Business of Caricature in Paris, 1829-41." The Art Journal. 43: 4 (Winter): 347-354. Danjoux, Ilan. 2007. "Reconsidering the Decline of the Editorial Cartoon." PS: Political Science and Politics. 40: 2 (April): 245-248. Desbarats, Peter and Terry Mosher. 1979. The Hecklers: A History ofCana- dian Political Cartooning and a Cartoonists' History of Canada. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart IJOCA:.'Fall/Winter 2014

- 29. 360 Dewey, Donald. 2007. The Art ofIll Will: The Story ofAmerican Political Cartoons. New York and London: New York University Press. Donald, Diana. 1996. The Age ofCaricature: Satirical Prints in the Reign of George III. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Dyrenfurth, Nick. 2010. '"Truth and Time Against the World's Wrongs': Montagu Scott, Jim Case and the Lost World ofthe Brisbane Worker Cartoonists." Labour History. 99 (Nov.): 77-110. Dyrenfurth, Nick and Marian Quartly. 2009. '"All the World Over': The Transnational World ofAustralian Radical and Labour Cartoonists, 1880s to 1920." In Drawing the Line: Using Cartoons as Historical Evidence, edited by Richard Scully and Marian Quartly, pp.06.1- 06.47. Clayton, VIC: Monash University ePress. Fabian, Suzanne. 1982. Mr. Punch Down Under, Richmond, VIC: Green- house. Feaver, William [and Ann Gould. ed.]. 1981. Masters ofCaricature-- from Hogarth and Gillray to Scaife and Levine. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. Gardes, Jean-Claude, Jacky Houdre, and Alban Poirier, eds. 2011. Ridiculo- sa, 18 -- Les revues satiriques fram;aises. Brest: EIRIS and l'Uni- versite de Bretagne Occidentale. Gatrell, V. A. C. 2006. City ofLaughter: Sex and Satire in ]8th-Century Lon- don, London: Atlantic. Gillin, Paul. 2007. Newspaper Death Watch. Available at <http://newspaper- deathwatch.com/about-2/>. Accessed March 5, 2014. Goldstein, Robert Justin. 1989a. Political Censorship of the Arts and the Press in Nineteenth-Century Europe. New York: St. Martin's Press. Goldstein, Robert Justin. 1989b. Censorship ofPolitical Caricature in Nine- teenth-Century France. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press. Goldstein, Robert Justin, ed. 2000. The War for the Public Mind: Political Censorship in Nineteenth-Century Europe. Westport, CT and Lon- don: Praeger. Gombrich, E. H. 1963. "The Cartoonist's Armoury." In Meditations on a Hobby Horse; and Other Essays on the Theory ofArt, pp.127-142. London: Phaidon. Graham, P. A. 1974. Community and Class in American Education, 1865- 1918, New York: Wiley. Hale, Oron James. 1940. Publicity and Diplomacy: With Special Reference to England and Germany, 1890-1914. New York and London: Ap- pleton-Century Co. Hess, Stephen and Sandy Northrop. 2013. American Political Cartoons: the Evolution of a National Identity, 1754-2010. New Brunswick and London: Transaction. Hicks, Marianne. 2009. "Teh Futar: The Power of the Webcomic and the IJOCA, Fall/Winter 2014