A Qualitative Study Of Managerial Challenges Facing Small Business Geographic Expansion

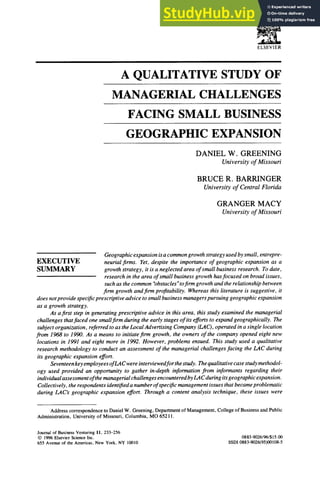

- 1. ELSEVIER A QUALITATIVE STUDY OF MANAGERIAL CHALLENGES FACING SMALL BUSINESS GEOGRAPHIC EXPANSION DANIEL W. GREENING University of Missouri BRUCE R. BARRINGER University of Central Florida GRANGER MACY University of Missouri Geographic expansion isa common growth strategy used by small, entrepre- EXECUTIVE neurial firms. Yet, despite the importance of geographic expansion as a SUMMARY growth strategy, it is a neglected area of small business research. To date, research in the area of small business growth hasfocused on broad issues, such as the common "obstacles ~toflrm growth and the relationship between firm growth and firm profitability. Whereas this literature is suggestive, it does notprovide specificprescriptive advice to small business managers pursuing geographic expansion as a growth strategy. As a first step in generating prescriptive advice in this area, this study examined the managerial challenges thatfaced one smallfirm during the early stages of its efforts to expand geographically. The subject organization, referred to as the Local Advertising Company (LAC), operated in a single location from 1968 to 1990. As a means to initiatefirm growth, the owners of the company opened eight new locations in 1991 and eight more in 1992. However, problems ensued. This study used a qualitative research methodology to conduct an assessment of the managerial challenges facing the LAC during its geographic expansion effort. Seventeen key employees ofLA C were interviewedfor thestudy. The qualitative case study methodol- ogy used provided an opportunity to gather in-depth information from informants regarding their individual assessmentofthe managerial challenges encountered by LAC during itsgeographic expansion. Collectively, the respondents identified a number ofspecific management issues that became problematic during LAC's geographic expansion effort. Through a content analysis technique, these issues were Address correspondence to Daniel W. Greening, Department of Management, College of Business and Public Administration, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211. Journal of BusinessVenturing11, 233-256 © 1996Elsevier ScienceInc. 655 Avenueof the Americas,New York, NY 10010 0883-9026/96/$15.00 SSDI 0883-9026(95)00108-5

- 2. 234 D.W.GREENINGET AL. organized into 15 thematic categories including training, recruitment and selection, the relationship between thefield staffand the original owners, and 12 others. Each of these categories represents the separate managerial challenges faced by the company during its geographic expansion. The study provides a descriptive analysis of each of the 15 categories of managerial challenges that emerged. The research results suggest that the successful management of a geographic expansion growth strategy requires managers to deal with a unique set of issues. For example, the training of new employees may become problematic when the most experienced personnel in thefirm reside in the home office and the new trainees are located in widely dispersed geographic locations. In addition, the results ofthe studyprovide an extension to bothpracticaland theoretical knowledge in three distinct areas: planning for growth, managing growth, and the reasons for growth. First, the results of the study support the importance ofplanning for growth, but suggest that planning must be complemented by learning and a willingness to evolve one's plan as growth progresses. In terms of the management of growth, the case shows that running a small business and growing a small business do not include the same skill set. The owners of LAC had been quite successful managing their single location for 22 years. However, this ability to run a business did not complement the need to anticipate start-up problems in new, remote sites, which is inherent in a strategy of geographic expansion. In addition, the case demonstrated that the management of growth requires a cognizance on the part of the original owners of a firm to delegate control. Finally, with regard to the reasons for growth, researchers generally characterize firm growth as being motivated by either economic (e.g. , economies of scale) or emotional reasons (e.g., employing family members). The owners of LAC initiated firm growth for the purpose of wealth creation to fund their retirements. This illustrates that firm growth can be motivated by a combination ofboth economic (e.g. , wealth creation) andpersonal (e.g. , retirement security) reasons. INTRODUCTION The academic and practical interest in the field of small business/entrepreneurship management has grown dramatically in the last decade (Low and MacMillan 1988; Stevenson and Jarillo 1990; Wortman 1987). An important area of concern in this field has been the emphasis placed on the problems associated with the prudent growth (and associated success or failure) of such small, entrepreneurial ventures (Hills and Narayana 1989). A strategy used by many small businesses to achieve their growth objectives is one of geographic expansion. This strategy is a relatively straightforward approach to growth, which entails expanding a firm's business into addition geographic locations beyond its current domain. In broad terms, geo- graphic expansion provides a means of growth for firms that cannot benefit from additional economies of scale in their present location, but believe that their products or services may have a broader appeal in different markets. Geographic expansion also provides an alternative to more complex growth strategies such as acquiring unrelated businesses or developing new products and services through internal research and development. A geographic growth strategy is a common strategy used by small businesses in "fragmented industries" and is common in such industries as retailing, services, distribution, and "creative" businesses (Gripsrup and Gronhaug 1985; Porter 1980). The fragmentation of industries is characterized by a large number of small- and medium-sized companies with no firm commanding a large market share, and it is often caused by such factors as low overall entry barriers, absence of economies of scale or experience curves, high transportation or inventory costs, or simply "newness" (Porter 1980). Surprisingly, despite the prevalence of geographic expansion as a means of firm growth, this is a neglected area of small business research. In fact, in a survey of the small business

- 3. SMALL BUSINESS GEOGRAPHIC EXPANSION 235 literature, we did not find a single article dealing with this subject. To date, rather than focusing on the implications of specific growth strategies, small business researchers have examined broader issues, such as the common "obstacles" to firm growth (e.g., Hambrick and Crozier 1985; McKenna and Oritt 1981), the characteristics of high-growth firms (e.g., Hills and Narayana 1989), and the relationship between firm growth and firm profitability (e.g., Eriksson 1978; Schuman and Seeger 1986; McCann and Cornelius 1985). Although suggestive, this broad-based research is course grained in nature and does not provide explana- tions or specific prescriptive advice (Amit, Glosten, and Muller 1993) to small business managers considering geographic expansion as a growth strategy. The purpose of this study is to provide a foundation for future research dealing with the geographic expansion of small firms. For small firms, geographic expansion involves unique challenges that are not common to other forms of firm growth. The common forms of firm growth include internal expansion (i.e., adding capacity to an existing facility), acquisition, franchising, and geographic expansion (Orsino 1994). Of these alternatives, only geographic expansion involves the "start-up" of a new operation in a potentially unfamiliar location. This aspect of geographic expansion involves the unique challenges of putting a new management team into place in each new location. Firms that expand internally do not face this challenge, and finns that expand through acquisition typically inherit a management team that either remains intact or can be built upon. Franchising may involve the start-up of a new operation in a potentially unfamiliar location, but it is typically the responsibility of the franchisee to assume the role and risk of putting the new management team in place. A related challenge that is unique to a strategy of geographic expansion is finding the optimal balance between autonomy and control while the new management team is progressing through the start-up phase of the business inthe expansion location. This challenge is accentuatedby small, relative to large, firm size. Small firms typically have limited managerial resources and may find that it is difficult to provide optimal levels of training, supervision, and management attention to dispersed geographic sites. The article proceeds in the following manner. First, a brief review of the research on small firm growth is provided. Much of the small business and entrepreneurship literature focuses on the broad reasons that underlie successfulbusiness expansion (Bygrave et al. 1988; Orsino 1994; Stevenson and Jarillo 1990). This study contributes to the literature by focusing specifically on the growth strategy of geographic expansion. Second, the qualitative case study is presented, including a discussion of the methodology, the research setting, and the findings. The primary advantage of a qualitative case study is that it provides an in-depth and rich description of a specificcase, providing a startingpoint for theory developmentpertaining to the phenomenon of interest (Eisenhardt 1989). The qualitative case method is most appro- priate for exploring new topic areas when little is known about a particular phenomenon with the explicit goal of generating theory and identifying theoretical constructs. In this study, we are particularly interested in examining the specific managerial challenges that accompany a strategy of geographic expansion of small business. Finally, we discuss the implications of the findings of our results for managers and researchers. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND There is a relatively small body of literature on small firm growth, dealing primarily with the "reasons" for growth and the "content" of growth strategies. With regard to the reasons

- 4. 236 D.W.GREENINGET AL. for small firm growth, scholars who adhere to the organizational life cycle perspective see growth as a natural phenomenon in the evolution of a firm (Churchill and Lewis 1983). Other scholars see small firm growth as more of a strategic choice that is entirely within the control of the small business owner (Stanworth and Curran 1976; Sexton and Bowman-Upton 1991). In this strategic choice context, growth may be pursued for a number of economic reasons including increasing economies of scale in production, making more efficient use of resources, overcoming liabilities of smallness, or simply "wealth creation" (McKenna and Oritt 1981; Sexton and Kasarda 1992). In addition, scholars have noted that many small business owners attempt to expand their business for various emotional and personal reasons. These reasons include ego enhancement (seeing their business as an extension of their self-concept), self- realization (becoming a complete unit), enhanced personal or community status, or simply to employ family members (McKenna and Oritt 1981). The content of small business growth has also attracted research attention. The content of small business research is an important area, because it provides practical advice to small business owners on how to achieve growth objectives. Unfortunately, most scholars who have addressed this topic have done so from "a purely conceptual perspective or have relied primarily on anecdotes as the basis for verifying their assertions" (Covin, Slevin, and Covin 1990, p. 392). There are several notable exceptions, none of which specifically addresses the growth strategy of geographic expansion. Covin et al. (1990) examined the business strategies used by small, growth-seeking firms in high- and low-technology-intense industries. They found that growth-seeking firms in high-tech industries tended to rely more on advertising, external funding, customer service, and emphasized product-related issues more than their low-tech industry counterparts. Lynn and Reinsch (1990) examined diversification patterns among small businesses, concluding that the owners of small businesses typically diversify for the purpose of wealth creation and do so by starting rather than acquiring a related business. Finally, a number of small business researchers has suggested that small businesses benefit from pursuing niche or focus strategies rather than the broader based strategies of cost leadership or differentiation (e.g., Cooper, Willard, and Woo 1986; Stuart and Abetti 1987; Wright 1987). There are a number of managerial challenges that face small firms attempting to grow. A prominent concern is the ability of the initial founders to administer a larger company than the one they originally created (Bird 1989; Sexton and Bowman-Upton 1991). The skill set necessary to start and manage a small business may also be very different from the skill set necessary to manage the growth process and the resulting larger company (McKenna and Oritt 1981). Other human resource issues that must be managed effectively to achieve satisfac- tory firm growth include delegation, training, motivation, information management, and the honing of communication skills (Miller 1963; Bird 1989). Given the lack of empirical research in the area of small firm growth, theory development can still be considered to be in its formative stage. Whereas the literature on small firm growth has grown in recent years, many theoretical explanations and normative prescriptions to entrepreneurs remain (Amit et al. 1993). Qualitative case study research is a means ofproviding rich description and developing theory to fit into the larger context of social science (Schmitt and Klimoski 1991). It is also a most appropriate methodology to extend thinking and theory in small business expansion. The in-depth case study approach used in this study has the potential to develop contextual and topical details to provide a rich understanding of important issues (Dyer and Wilkins 1991) and can provide additional data to add incrementally to more powerful, robust theory development. In the next section we discuss the methodology utilized to investigate this topic. This includes a discussion of the research setting, the subjects, nature of data, and the analysis techniques.

- 5. SMALLBUSINESSGEOGRAPHICEXPANSION 237 METHODS Research Setting LAC produces and distributes a weekly advertising publication that "attempts to offer value to area residents while providing effective response to advertisers" (taken from its mission statement). The mission statement further states that the organization endeavors to "work to provide response to our advertisers through good offers, effective layout, and advertising in 'Local Advertising,' to our readers." The company serves both national and local advertisers within regional markets. LAC was started in a small town in 1968 by a wife and husband team who acted as president and vice president, respectively. The wife and husband founders have continued as owners as of this writing. Previous to its decision to expand to additional geographic markets, LAC had reached the maximum "manageable" page count (number of pages in its publication) considered readable by customers in its home-based market. In the year before the multisite expansion, LAC had secured the financial backing of a Fortune 100 company to fund the expansion. If the expansion efforts were successful, the national backer had contracted to purchase the entire group of LAC sites, essentially allowing the owners to retire as millionaires. LAC's geographic growth strategy was to expand to similar markets with the same kind of local advertising publication used in its home market. The owners of the company opened sites in eight new locations in 1991 and eight more in 1992. New sites were located throughout the United States and included southeastern, eastern, midwestern, western, and southwestern locations. Positions at each new site included an associate publisher (the head of each site), a general manager (responsible for overseeing distribution as well as sales), a sales representa- tive, a distribution manager, an assistant distribution manager, and a distributor. Publications were produced centrally for each site location at the home office. Research Methods The owners of LAC contacted the principle investigator (PI) for assistance in assessing problems they were encountering during their geographic expansion. The owners wanted the PI to perform an independent assessment of the problems they perceived. They deliberately did not reveal any of their perceptions to avoid biasing the PI. In this sense, the basic research question was defined before entering the field, but no specific constructs were formulated. The owners disclosed that of the 16 sites opened in two years, only one was currently operating up to financial expectations, although they did not expect any of the site locations to be profitable the first year. The research problems were defined as managerial, communication, and/or organizational problems associated with geographic expansion, in contrast to research questions about financing, economic, market, or regulatory factors on such expansion. ~Figure 1 illustrates the context of the entrepreneurial venture under investigation and demonstrates the growth from LAC's situation from 1991 to 1993. It was agreed that the PI would conduct telephone interviews with employees at the new locations (predominantly associate publishers and regional managers), as well as the owners after the staff interviews were conducted. The explicit purpose of the interviews was to solicit organizational members' perceptions of the problems, difficulties, and success factors related to the opening of the 16 new geographic locations. An e-mail message was sent by the president tit shouldbe notedthat while someauthors focuson studyingsmallbusinessgrowth from an economicor regulatoryperspective(Amitet al, 1993;Stevensonand Jarillo 1990),this study focuseson the humanresources managementand organizationalbehavioraspectsofeffectivelymanaginga geographicalexpansiongrowthstrategy.

- 6. 238 D.W.GREENINGET AL. Local Advertising-Pre Expansion, 1991 Local Advertising Company Home Office One Location Eleven Employees Local Advertising-Post Expansion, 1993 Local Advertising Company Home Office Seventeen Locations One hundred, Twenty Employees West ~Midwest I Southeast East i l l l n Regional Office Regional Office Regional Office Regional Office I I I I Five Local Sites Five Local Sites Four Local Sites Three Local Sites Thirty five Thirty four Twenty six Twenty Employees Employees Employees Employees FIGURE 1 LAC pre-expansion and post-expansion. to each employee indicating the nature of the study, that the home otfice had retained a professional business educator to conduct the study, that they may be contacted by the PI, that they should be completely honest with the PI, and that all remarks would remain completely anonymous. The interviews were conducted between October 15, 1992 and January 15, 1993. Subjects The interviews were conducted with both owners of LAC, the four regional managers (RMs), eight associate publishers (APs), two salespersons (SPs), and one general manager (GM). The sampling procedure to select these informants can be considered a purposive sampling (as opposed to random, systematic, or stratified). The sampling assured that all informants were knowledgeable about the start-up problems and that all sites were represented. It was thought that the regional managers and associate publishers were most knowledgeable about the initial problems. At the time of the interviews, the GM position was being phased out. There was only one GM in the organization at the time of the interviews.

- 7. SMALL BUSINESS GEOGRAPHIC EXPANSION 239 Data and Analysis The qualitative research method used was intended to capture company members' rich array of subjective experiences during geographic expansion, or what organizational members referred to as start-up. Each person interviewed by the PI was very clear about why he/she was being called, and every staff member appeared willing to discuss their many concerns about the effectiveness of the geographic expansion of LAC. After identifying himself, the PI reassured each member of the anonymity and confidentiality of his/her responses indicating that only themes or patterns would be reported across respondents. After confirming their position in the company, the informants were asked an open-ended question: The owners of LAC have mentioned that there have been some problems and successes with the rapid growth of their company, but they, at this time, have intentionally not told me specifically what they perceive them to be. Rather, they want me to conduct an independent study to assess what others in the company, such as yourself, think they are. From your perception, can you tell me what you think were, or are, some problems, or issues, or success factors at your site or at other sites during start-up? This open-ended question was designed to articulate clearly the research question under investigation without specifying preordained constructs or investigator bias. Depending on the informant's responses, the duration of the interviews ranged from 45 minutes to 2.5 hours. Each respondent's comments were tape recorded and later transcribed. Seventeen interviews were conducted. Interviews were analzyed by means of a content analysis technique (Berg 1989; Miles and Huberman 1994). This technique was chosen to condense data systematically and to identify patterns in the data. This made the data meaningful and allowed comparison with the literature on small business growth to determine if a strategy of geographic expansion encompassed unique managerial challenges. Content analysis is a technique designed to make "inferences by systematically and objectively identifying special characteristics of messages" (Holsti 1968, p. 608). After the interviews were transcribed, an initial open coding procedure was conducted (Berg 1989) at the sentence level of analysis with each sentence being assigned a "theme" or "category" given the specific research question under investigation. Following suggestions by Glaser and Strauss (1967), each sentence was carefully and minutely read to document the more general concept or category to which it fit. Then a more specific coding frame was used to assess specific subdimensions by considering specific"conditions, strategies, interactions, and consequences" (Strauss 1987, p. 28). The process at this stage was considered inductive, using manifest content analysis and in vivo codes (i.e., literal terms used by individuals). Two researchers (including the PI) coded the data after the fifth interview to begin to identify themes or patterns following prescriptions by Eisenhardt (1989) and Taylor and Bogdan (1984). The two researchers worked iteratively between the data and coding to identify both areas of similarity and difference (Denzin and Lincoln 1994). This process of iteration, transcription, and coding continued through the 17 interviews. After subdivisions of each category were determined, the researchers analyzed deductively the data for latent and sociologic constructs (Berg 1989) to both ground the data in existing theory and to generate new theory (Miles and Huberman 1994). RESEARCH FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS A process observation made by the PI was that all the staff interviewed were very clear about why they were being contacted and appeared willing to discuss their concerns about the

- 8. 240 D.W. GREENING ET AL. TABLE 1 Thematic Categories Identified in Content Analysis Frequency of Duplicate Mention Category Respondents by Respondents 1. Training (N = 17) 2. Recruitment, selection (N = 17) 3. Relationship with owners (N = 17) 4. Compensation, guaranteed commission (N = 16) 5. Work loads (N = 13) 6. Forms, reports, paperwork, computer equipment, e-mail (N = 10) 7. Bonus and page counts (N = 8) 8. Specific problems with start-up (N = 8) 9. Conversion difficulties (N = 8) 10. Distribution problems (N = 7) 11. Relationship with regional managers (N = 6) 12. Relationship with production and accounting (N = 6) 13. Vacation and benefits (N = 6) 14. Servicing accounts (N = 5) 15. Other areas of concern: (N = 1-3) personal recognition empowerment individual differences in sites relationship with backer need for additional staff (D = 9) (D = 3) (D = 3) (D = 5) (D = 3) (D = 1) (D = 3) (D = 2) problems encountered during the start-up phase at their new location. The PI also observed that almost all of the staff members experienced strong emotions related to the expansion, which we demonstrate with several quotations from the informants. Table 1 presents the general thematic categories of concern that were expressed by the staff members interviewed regarding the geographic expansion of LAC. The frequency of each response by the 17 respondents is also shown in Table 1. This combination of simple, quantitative, descriptive analysis was conducted to triangulate and provide reliability for the identified themes. The frequency analysis in Table 1ensured that "vivid, but false impressions" (Eisenhardt 1989, 1991) were not regarded as more meaningful and pervasive than otherwise might be inferred without such frequencies. These categories of concern represent the separate "managerial challenges" faced by the company during its geographic expansion. Whereas space limitations preclude a complete presentation of the findings, we next present relevant findings for the most common problems expressed by the informants in Table 2. Several quotations are also provided in the following sections both to show the in vivo responses of staffmembers and to illustratethe high emotional states they experienced. After the presentation of our results, we discuss the value-added contributions of our study for a theory of small business expansion. Training All 17 informants mentioned problems with the training of staff. LAC brought in staff for the new sites in June (before a September opening) for a week of training at the home office. Most staffhad few problems with the actual content of the training but they mentioned problems with the process of training. The problems mentioned included an overemphasis on lecture and not enough interactions, such as role plays. Several of the informants mentioned that the

- 9. SMALLBUSINESSGEOGRAPHICEXPANSION 241 methods of training could be improved through the use of different media, such as videos, tapes, etc. I mean, you sit and sit for eight hours a day and listen to someone lecture at you. We should have been role playing and using videos. One of the most strongly felt responses to training was that it should not be a one-time event at the home office, but that it should be done on a more continuous basis at the regional level. An interesting finding was that many of the informants felt that although the staff conducting the training were indeed, knowledgeable people about LAC business, they were deficient in knowing how to train. This was supported by comments regarding the overemphasis on lecture and the failure to include what the staff identified as process activities (i.e., role plays, videos, tapes). One staff member commented: The trainers knew their stuff. They know how to sell; they know how to service accounts. Unfortunately, they don't know anything about how to train people. Whenever turnover occurred, training was conducted on an ad hoc basis at the company site by an owner or regional manager. Some staff thought new people should be brought into the home office for training as opposed to training in the field. This ad hoc training was clearly not as extensive or exhaustive as the week of training in June before a new September start-up. Another staff member commented on both aspects of the training: People turned over, and they tried to just train them in the field. It also shouldn't be a one-time event in June. Who, nowadays, thinks you can train people in a week? The problem of training new staff members during the geographic expansion of small business in the field as opposed to the home office appears to be a specific difficulty associated with this type of growth strategy. Many new staff trained only in the field indicated that they felt "left out in the cold" as a result. Recruitment and Selection Another problem mentioned by all respondents (including both owners) was the hiring and firing of staff. Respondents disclosed that many problems persisted at the new sites because new hires, that later proved to be unqualified or undedicated, were allowed to remain on staff too long before dismissal. Several respondents recommended that new employees should have a media background as many of the hires had no such background. Additional comments related to hiring staff who could "sell" but didn't know how to "service" an account. This problem caused many accounts to cancel. One member commented that "hiring was critical! We have good people now. When you're rolling out new markets.., the best people are so critical." There were also some comments about conflicting messages given to staff during the interview process concerning training, work load, and potential income. Regarding potential income, one staff member stated; I don't know what three or four people are saying to them, but they're getting conflicting messages. A GM was hired today and quoted a figure higher than another GM. There is a problem of what was said, what happened in the hiring process. There are too many people or... oh, it's so confusing. Another member said, "it's a bold-faced lie about how much money you can make." However, the owners took issue with this during their interviews, and it appears that this miscommunica-

- 10. 242 D.W. GREENING ET AL. TABLE 2 Specific Topic Areas for Thematic Categories Thematic Category Specific Topic Areas 1. Training 2. Recruitment selection 3. Relationship with owners 4. Compensation guaranteed minimum 5. Work load 6. Forms, reports, paperwork 7. Page counts/bonus 8. Start-up difficulties Need for consistent, ongoing developmental training versus one-time event. Trainers knowledgeable as to content and process of selling and managing business, but unskilled in the process of training. A variety of training methods and mediums should be used. Difficulty in hiring qualified and dedicated staff. Unqualified staff allowed to remain too long. Conflicting messages given to staff regarding compensation, benefits, vacation, and work load during recruitment. Geographic expansion had grown to stage where owners needed to rethink their roles. Some staff felt reluctance of owners to let go of hands-on control of remote sites. Excessive involvement in hiring and day-to-day operations. Need to delegate responsibility to regional managers and associate publishers. Inconsistency in owners' division of labor, as specified and carried out in prac- tice. Conflicting and inconsistent messages from home office. Too much top- down management. Vision of home office as police force. Authoritative. Personality conflicts with owners. Initial guaranteed minimum salary too high. No incentive to exceed minimum. Monthly increase in accounts requirement unstated. Compensation considered inequitable with work load. Compensation not adjusted for regional differences and to comparable external media positions. Excessive work hours for compensation. Inequities in work loads. Sales should be given more to sales staff than to associate publishers. Unnecessary red tape and paperwork at all levels. Need for efficient computer software to help in information dissemination. Unrealistic page counts needed for AP to receive bonus. Inappropriate adjustment period for changing bonus (changed to quarterly ad- justment period). Overemphasis on page count to exclusion of proper training to reach page count. Inappropriate preparation, hiring, and motivation. Need for experienced man- ager to head up new site development. Need for staff in place earlier. tion occurred at the regional or local site level rather than from the home office. The unique challenge associated with small business geographic expansion identified in this category is the time, effort, and level of attention that normatively "should" be allocated to finding appropriate personnel that match the particular demands of the assigned site location positions. This appears to be a most important challenge given the lack of direct control and oversight by owners as they attempted to manage from afar. Relationship with Owners Every respondent also expressed concern about their relationship with the home office. There were comments that it was time for the owners to rethink their roles and responsibilities with regard to their direct involvement with the different geographic sites. Many of the informants felt that the owners needed to get out of the day-to-day affairs and become more long-term-

- 11. SMALL BUSINESS GEOGRAPHIC EXPANSION 243 TABLE 2 Continued Thematic Category Specific Topic Areas 9. Conversion problems 10. Distribution 11. Relationship with regional managers 12. Relationship with production and accounting 13. Vacation and benefits 14. Servicing accounts Lack of planning. Need for appropriate planning time horizon at all levels. Limit start-ups to three a year. Motivational problems with start-up period and compensation. Criticality of conversionperiod. Possibility of losing 100% of accounts. Incredi- ble tensionduring conversion. Loss of dissatisfied customersduring conversion. Difficulty in maintaining same accounts sold in home office area. Need to con- sider competition, economy, local circumstances. Difference between sellingand servicing accounts. Need to train staffin servic- ing accounts as well as selling them. Need to pace selling to cultivate accounts. Staffing distributors is major problem. Very high turnover rate. High rejection rate. Excessive use of transients, alcoholics. Responsibility for distribution unclear. GM compensated for sales but given distribution responsibility. Everyone helps on distribution day. Insufficient empowerment given to RMs. Roles and responsibilities unclear. Spend excessive time "fire fighting." Owners not in touch with RMs. Miscommunicationamong reporting lines. Inconsistentreporting of APs. Some report to RMs and some directly to owners. Reporting to RMs not encouraged by owners. Goals of regional managers' visits with remote sites unclear to associate pub- lishers. Large number of mistakes and inconsistency in quality from production. Incon- sistency in product offered by sales reps and product delivered by production. Lack of appropriate relationship between sales staff and paste-up people and typesetters. Creative ideas by production assistants suppressed. Lack of support to production. Problem of centralized production. Need for APs to work closely with produc- tion in home office (centralized production). Inadequate benefits. No compensation time or sick leave. Confusion in this area. Difficulty in taking vacation and coverage of accounts. Excessive work load not conducive to vacation. Need to service as well as sell accounts. Time managementdifficult. Contributes to only selling accounts. Pressure to sell precludes servicing accounts. Need to emphasize servicing accounts during training period. Very important in retaining accounts. oriented and decentralize authority. However, an owner commented: "you cannot decentralize unless you have qualified staff you can trust to do the job right." They apparently didn't. This difference of opinion regarding diffusion of control and delegation illustrates an aspect of the emotional tension evident in LAC's geographic expansion. The owners attempted to divide their responsibilities, with one owner handling production and the other owner handling selling and staff training. Most of the respondents indicated that although this may have been the way the division of labor was formulated, it was not always implemented that way. Staff often received phone calls or e-mail messages from owners and/or regional managers with conflicting messages about how to proceed with an account or procedure. Some examples illustrate this inconsistency: Pat (an owner) tells an AP to do one thing, then Terry (the other owner) gets involved and tells them to do something different. (Regional Manager)

- 12. 244 D.W.GREENINGET AL. I get one answer from my regional manager, one from Terry, and one from Pat. You know you are going to upset someone when that happens. (Associate Publisher) • . . Ah, well, we have had some inconsistencies in direction from the home office. (Owner) Similar to comments about recruitment and selection, several informants mentioned that "the owners have a hard time letting go" and that "Terry and Pat should get out of the day-to-day operations, they shouldn't be talking with AP and GMs." One member said "leadership in the field is neutralized from the home office." Additionally, one member said, "they have a hard time trusting people." Some interesting perceptions of the home office by site staff members included the use of such metaphors as the "boss" or the "police force." Underlying these metaphors was a perception of the home office as "resistant to new ideas and generally punitive rather than supporting or recognizing accomplishment in the field." However, this perception was not completely uniform as some informants had good relationships with the owners and saw them as good listeners. There were also comments about the personalities of the owners. The owners were perceived as opposites-one being perceived as "thoughtful, organized, and liking a structured environment" and the other perceived as "creative, active, idea-oriented, and occasionally disruptive." The owners agreed with these characterizations. The difficulties in the diffusion of responsibility as firms grow and the inconsistency in messages when one has two (or more) bosses is not unique to this research setting. However, the geographic distance between several remote locations and the paucity of resources relative to large firms exacerbates problems associated with these miscommunications or at least makes attempts to rectify them more difficult. The delineation and clarification of authority and domain responsibilities appear to take on increased importance with a geographic growth strategy. Compensation, Guaranteed Commission All staff interviewed (including the owners) mentioned problems with the original compensa- tion system, especially the guaranteed minimum. The guaranteed minimum was a compensa- tion system in which the sales representatives were guaranteed a minimum monthly income regardless of their individual monthly sales. They did, however, receive a commission if sales exceeded a certain sales threshold. Many sales staff, however, were only generating a fraction of the amount they needed to receive a commission, and, as a result, they had little motivation to generate enough sales to earn a commission. Several comments regarding the pay sale include the following: Compensation is fair for the reps, but the guarantee also reduces motivation for people to work. Sales, very fair, but no one is going to get to base. Would get there if % of pay increased. Only one rep higher than base now. There is no stimulus to get higher than base. It could be a deterrent, not a motivator. This problem was widely recognized, and, while the interviews were being conducted, the owners were revising the compensation program. In order to retain the guaranteed minimum according to the revised compensation system, it was then necessary for sales representatives to sell two additional companies per month after a three-month starting grace period expired. All staff saw this as being very fair (including sales reps). Several of the staff mentioned being unfairly compensated for the work load they were

- 13. SMALL BUSINESS GEOGRAPHIC EXPANSION 245 TABLE 3 Sample Comments for Work Load Dimension Respondent Member Position Quotation about Work Load Associate Publisher "What are you doing there? You cannot run 40 accounts a week and be there 40 hours a week. How many hours did you work? No way you can do it in 40 hours. Monday I do .... Tuesday I do .... Wednesday I work until 11 P.M., Thursday until 1 A.M. Friday I try to get out by 7." "To think an AP can make as many calls as a sales rep and do the other stuff is completely absurd. They can't possibly do that. They (the owners) need to rethink the work load the APs have." "The workload with the APs is very, very, very heavy.., involved with distribution with GMs even though we are not supposed to, account managers, community relations, training, and on and on and on." "It's very, very frustrating for me, there are so many responsibilities, hard to prioritize what to do, one of my staff left and when he left he said 'you are so incredibly understaffed.'" "For all our staff, we ask so much of them, more than any other company. What's in it for them? We've got burn out like you couldn't believe. July to September. It never lets up. A criticism by employees is "who will do my work if I can't come to work?"~ "Job is all consuming. Leave Sunday P.M. and get home midnight Thursday and work all day Friday. Sundays too. I make the same as I did as a sales rep." Associate Publisher Associate Publisher General Manager Associate Publisher Associate Publisher expected to carry. The APs and GMs were expected to carry full sales loads as well as train and motivate sales staff. However, whereas GMs were compensated on a commission basis, the APs were salaried with bonuses above a certain page count (considered unrealistic by most APs-and the owners). One owner said, however, that not all APs and GMs carried full sales loads. This leads to a discussion of staff work load. Work Load This category of concern elicited the greatest emotional response from the subjects. Table 3 lists some of the more emotional comments made by APs and GMs concerning work load. It can be seen in Table 3 that the APs and GMs had very, very strong feelings about the inequities in the work load for the compensation they received. Many of the APs thought that their sales loads should be reduced and given to sales reps. This way the APs could help the sales staff with their selling without any loss of service or addition of staff, and, concomitantly, it would help the sales staff reach their minimum base faster. Forms, Reports, Paperwork, and Bonus/Page Count Categories These two categories are related to the work load category, so they are discussed together. As with the growth of all businesses, there was an increase in reports and paperwork as this firm expanded to multiple geographic sites. Some informants thought the paperwork was "excessive, overly complicated, and needed to be streamlined to increase efficiency," and that there was an overabundance of gathering of information that was not used. The following comment by one member clearly illustrates the feeling here: We have to report on sales, attempts, calls, successes, new contracts, dropped accounts, production problems, collection, competitions, goals, etc. in a 5-15 report that is supposed

- 14. 246 D.W.GREENINGET AL. to take 5 minutes to read and 15 to prepare. No way you can do it in 15 minutes-it's a joke. Clearly, almost all staff thought the reporting process could be improved. APs received a bonus for additional pages of sales beyond a minimum number. The owners and APs agreed that the original page counts for a bonus were unrealistic and that they should have been adjusted earlier in the expansion period. The unrealistic page counts created motivational problems for the APs, because the GMs and sales reps worked on a commission basis. One AP stated: Most don't see the compensation as fair at the AP level, almost impossible to get page count for bonuses. The carrot is 50 feet in front of APs. People we hire want to work 8-5, not 60 to 80 hours a week. We need some immediate rewards. There were also comments that APs did not make comparable money to other similar media people in their area. APs also thought that their compensation should be adjusted for regional economic differences, such as cost of living differences. Start-Up Problems and Conversion Difficulties Several staff (N = 8) mentioned some specific problems with the preparation and initial start-up period at the new locations. One area of concern focused on the inadvertent hiring of unqualified staff in certain positions and tardiness in replacing them. This led to motivational problems with the sales representatives shortly after start-up. It was very difficult, given the guaranteed minimum, for staff to make a commission during the start-up period, and "many sales reps felt they should have been rewarded for their effort and not for their successes." There were other indications that planning for the start-up phase was not adequate. For example, some staff made comments related to an inadequate advertising budget, difficulty in "trading with radio stations due to our lack of reputation," and the challenges of coping with inadequate equipment and facilities. One respondent indicated: The day before opening we were getting e-mails and phone calls telling us what we should doing right before opening. That was nuts! We should have had the information at least a month earlier. There was also concern that: There was no formal evaluation of the start-ups ,and if it is done, it is done months down the road. Conversion problems also related to the maintenance of advertisers. Businesses advertis- ing in LAC's publication signed up for a specific time period. At the end of the contractual period, they could cancel or continue their advertising. The end of the period was called conversion, as accounts could be converted into full-time accounts or canceled. Comments from the respondents indicated that conversion was an incredibly dramatic time for the staff. One staff member said: Theoretically, you could lose 100% of your accounts, and with the potential of a massive cancellation, you are building in a suicide rate! Others remarked that "what you need to do is sign up people slowly and methodically," and that "some sites have signed up people in a hurry, and they tend to have higher cancellation rates." In discussing conversion, many staff talked about the difference between selling an

- 15. SMALL BUSINESS GEOGRAPHIC EXPANSION 247 account and servicing it. It appeared that accounts that were only "sold" and not "serviced" tended to drop out more frequently at the conversion time. One AP offered: My recommendation is to prepare better by having the complete staff in place earlier. Bring the AP in first for four-six weeks to operate alone.., would like to have staff in place earlier. Bring the entire process up front earlier. We begin the first week of June now; we should start that much earlier. Regarding the pace of the start-ups, one staff member disclosed that: We should have one staff member in place that has gone through the process of start-up before. Could be anyone that has gone through the 24-week conversion period. Another member said: There are definite time constraints with planning new start-ups. We shouldn't do more than three a year. APs should be thinking four to six weeks ahead, RMs four to six months ahead, and Pat and Terry two to five years ahead. Several staff members also mentioned the difficulty the owners had in understanding why accounts that sold in the home office area could not be sold or didn't make conversion in the remote sites. One staff's comments illustrate how the owners had become capable of running an established company but appeared to have forgotten the initial difficulties it took to secure accounts. There were three accounts the home office has had for a while. They asked us why we couldn't keep them as they could at home? They don't understand it's different here. We're not established! Another AP disclosed: Pat and Terry know how to run an ad company. I am not sure they still know how to start one. They don't understand that radio stations just won't trade with us. They don't know who we are! These multiple problems during conversion serve to highlight the added difficulty of attempting to learn the ropes from experienced staff located in a distant location (the home office). Distribution, Regional Managers, Production and Accounting, Vacation and Benefits, Servicing Accounts These categories are treated more briefly, because less than half of the respondents mentioned them as areas of concern. Problems with distribution mostly centered around the high turnover and poor dependability of the individual staff distributing the advertising brochures. One problem in the distribution process was that the GM was primarily responsible for the distribu- tion of LAC's product but was rewarded for sales. There was also some concern about who was actually responsible for distribution, as the sales reps and APs occasionally had to assist with distribution to "pick up the slack to get the product out." Some APs reported through their RMs, whereas others talked directly to the owners at the home office when they had questions or problems. There was some concern that RMs were not sufficiently empowered to carry out their roles, and some staff were unclear about when, or why, RMs would be visiting them.

- 16. 248 D.W. GREENING ET AL. The goals of their visits are unclear to me. I think we need to rethink the roles and responsibilities of the RMs and the authority given them. The RMs do not feel empowered; they spend their time putting out fires now. All this running around cost (name of city) a lot of money. If they had been in touch, they would have fired (name of person, an AP) sooner. There was some concern related to the lack of consistent quality in the production area (which was centrally produced at the home office for all geographic sites). Some staff were concerned, because they had told their clients that: We were going to put out a quality product, and then we put out a product with errors and problems-with tons of mistakes! There was also some concern that some of the production staff (who worked with two to three sites) had some good ideas for improvement, but they were never listened to by their supervisor, "they are just hung out in limbo." Some staff felt that the vacation and benefits were inadequate, but the most frequent concern was that, due to the work load, "it is impossible to take vacation here." "Who is going to cover my 50 accounts during vacation?" The concern for servicing accounts had been mentioned, but staff felt that accounts needed to be serviced as well as sold and that this "should be stressed during the training period." "We learned this too late!" DISCUSSION Our qualitative, case study approach to small business geographic expansion has provided both a rich description of the specific growth process and has generated a number of valid, interesting, and testable research issues that are linked empirically to direct evidence (Eisenh- ardt 1989, 1991; Miles and Huberman 1994). The research results suggest that the management of geographic expansion is likely to involve a series of managerial and communication diffi- culties that may be different from a capacity enlargement or a product extension growth strategy. The results of the analysis indicated to us an extension of theoretical knowledge in three distinct areas: planning for growth, administration of growth, and the reasons for growth. Table 4 lists the theoretical advancements and predictions formed from our interpretive analyses. Planning Growth A clear theme in the small business literature is that business growth requires careful planning (Shuman, Shaw, and Suissman 1985; Bracker, Keats, and Pearson 1988). Based on the findings of our study, we would extend the simple notion of careful planning. Even planned growth may be more problematic than anticipated previously. For example, our research suggests that there were a number of issues that the owners of LAC had no means to anticipate and consequently could not plan for. The next section examines this point more closely by discussing two related, but equally important issues: the need to plan and the need to learn and to evolve one's plans as growth progresses. With regard to the importance of planning, the experience of LAC clearly supports the thesis that geographic expansion must be preceded by careful planning. Several examples from the case illustrate this point. First, a number of the staff comments were related to compensation and work load (Tables 1 and 2). These compensation and work load concerns

- 17. TABLE 4 Theoretical Predictions and Advancements from LAC Study Category for Theory Extension Specific Issue Case Illustration Theoretical Prescriptions and Advancements Planning for Need to plan carefully Unanticipated problematic issues Ongoing "process and content" oriented training. Flexibility to adjust for regional growth and but flexibility in circumstances. expansion implementation Investigate local business conditions to develop fair compensation packages. Managing growth and expansion Reasons for growth and expansion Need to learn Owners' role in expansion process Changing skilllevel of entrepreneurs during expansion Life cycle progression Need to pace growth with ability to control, level of expertise, and appropriate training activities Economic or personal reason for growth Reasons for success may push growth too fast Reasons for growth preclude awareness of different local conditions Compensation difficulties Work load problems (emotional distress) Guaranteed minimum compensation revision Expansion site revision Failure to redefine owners' role Failure to change-continued day-to-day involvement (paradox not able to delegate or control) Owners became good managers of home location but not as knowledgeable in "starting" a business Owners attempt to manage 16 new locations in two years Owners expanded for wealth creation (economic) and retirement (emotional) concerns Owners and company grew too quickly with inability to manage and control expansion Problems due to attempt to ~replicate" home business Difficulty in expanding due to different competitors and stakeholders. Owners frustrated. Provide realistic job previews regarding work hours and effort levels. Hire consultants or professional managers. Expect to learn and develop as geographic expansion process progresses. Continually monitor and adjust geographic expansion and implementation plans. Consider new leadership ideas associated with management of multisites. Expect owners' roles to evolve and change with geographic expansion of firm. Awareness that growing a business requires different "owner" and managerial skills than "running" a business. Need for delegation, creation of structure. Manage information and resources prudently. Great care in selecting employees slowly. Paradoxically, entrepreneurial skills may diminish as "owners" learn to run a business. Retain entrepreneurial knowledge and style for "geographic expansion." Personal adjustments need to "lead" with competent staff and diffuse control and t" empower staff. Need to maintain control or delegate responsibility to competent, qualified, trained staff. Owners need to lead rather than manage during geographic expansion to develop, nurture, and grow staff. Develop management style for persistent growth with adequate training of staff. © Instill appropriate awareness of expected contingencies. ~ Trust staff. Allow freedom to innovate and be proactive. = Dichotomy of rationale for growth replaced with combination of both reasons. Growth through geographic expansion can be difficult process with great "personal" sacrifice for "economic" gain. Avoid temptation to emphasize quick expansion over incremental progress and Z profitability objectives. ~ Process of geographic expansion involves more than simple replication of existing home business-each start-up is a new venture due to local idiosyncratic differences. I~ 4~ Examine pace of growth, be aware of idiosyncratic differences in local ~,O stakeholder relationships and associated difficulties with expansion.

- 18. 250 D.W.GREENINGET AL. involve procedural and distributive justice issues, which research has shown to be very salient to employees (Alexander and Ruderman 1987). In the context of planning for firm growth, this raises several telling rhetorical questions. Were the new employees of LAC given realistic job previews before they were hired? Did the owners of the company study the cost of living variations between their dispersed locations before they set wage rates? These rhetorical questions are raised to illustrate the following point. At least part of the frustration of the new employees of LAC may have resulted from too little, or ineffective, planning with regard to "fair" compensation packages and expected work loads. As a result, although the owners of LAC may have known exactly what page count level would meet a break-even point, they may have treated compensation and employee work issues as secondary concerns. As a result, this situation created a very emotional human resource problem, with many of the employees at the new locations left wondering "what have we gotten ourselves into." It appears that these human resource problems can be avoided, at least in part, through proper planning and proper job previews. If addressing these issues exceeded the expertise or the time availability of the owners of LAC, they would have been better off in the long-run by hiring professional managers or retaining consultants to establish fair wage rates and to conduct realistic job previews before these problems developed. Second, our interpretation of the events in the geographic expansion of LAC reinforces the notion that planning is a learning process (Senge 1990). Several examples from the case illustrate this point. For instance, the owners of LAC did revise the original compensation program. This may have served the dual purpose of attracting more qualified employees and reducing firm-wide tension. In contrast, the owners' decision to continue with their initial plan to expand by eight locations per year for two years, even though they encountered a host of problems during the initial expansion, indicates a failure to learn from experience. This scenario supports McCarthy et al.'s (1993) findings regarding escalation of commitment to business expansion even in the face of negative feedback. As a result of their difficulties, however, the owners of LAC did move along a learning curve and changed their plans after the second year. In fact, they openly disclosed to the PI that they wished they had changed their plans after the first year and not added the additional second-year locations. These examples illustrate that it is possible, and critical, for owners to learn and to develop as the expansion process progresses. One should not expect planning to be a rigid road map that will foresee all eventualities. Planning is a learning process that implies periodic adjustment to compensate for unforeseen problems and opportunities. Ultimately, planning should also include a consideration of the owners' role in the future business. As an organization grows and changes, so do the role expectations and careers of the owners. There are many transitions that may require a redefinition of the owner's role through changes from founder to manager, leader, or ex-entrepreneur. The owners in this case did not initially redefine their roles. Whereas the owners' hands-on approach may have been appropriate given the quality of their initial applicants, this also led to frustration and many difficulties among the owners, regional managers, and associate publishers. Geographic growth requires a leader who is ultimately willing to delegate, create structure, and formally manage information and resources. It involves changing relationships among organizational members and, importantly, a changing relationship between the founder and his or her own firm (Bird 1989). Whereas many authors suggest that at some point the owner(s) may have to come to terms with stepping aside from active management of their enterprise, our results poignantly illustrate that this is only possible if qualified personnel are hired and are in place to assume responsibilities relinquished by the owners.

- 19. SMALL BUSINESS GEOGRAPHIC EXPANSION 251 Managing Growth As this case shows, running a small business and growing a small business do not include the same skill set (McKenna et al. 1981). For example, Quinn and Cameron (1983) and Starbuck (1965) have suggested that finns progress through definable growth stages including an entrepreneurial, collectivity, formalization, and elaboration stage-each stage associated with unique management problems, leadership styles, and administrative requirements. The owners of LAC had been quite successful with their one operation for 25 years. It appears that they developed their management skills in running and managing the local company but were unprepared for the demands the number of start-up remote sites provided. Similarly, their ability to develop appropriate training and compensation packages needed in geographically dispersed locations was ineffective. Our results offer an extension and interesting paradox to existing theory in small business expansion. Entrepreneurs may be able to grow with their company and learn to effectively manage their company to a certain size level. With a geographic expansion strategy, however, owners may not only need to learn to manage the disparate sites, they must likewise retain some of the flexibility and start-up skills that led to their initial success. It appears that the owners of LAC may have been perfectly capable of managing the business when it was small, but they were not prepared either technically or emotionally to administer the organization effectively through its growth phases. Furthermore, management of the postexpansion phase may also require a different set of skills than those necessary for firm growth beyond a minimal level. This involves the delegation and diffusion of control that we turn to next. It appears that if the original founders were to remain in control of the firm, they may have needed to make personal adjustments, obtain additional training, and change their norms of behavior as their company grew. A similarly interesting paradox to the one discussed previously involved the expansion efforts of LAC and the owners' delegation of control. Because of the rapid pace of expansion, the owners were neither able to maintain adequate control themselves, nor were they able to fully delegate control to the personnel in the new locations. It is unclear whether this situation developed as a result of the pace of the expansion, the owner's unwillingness to "let go" after 25 years of direct control of their business, or the limitations imposed by staff that was either not properly qualified or properly trained, or some combination of these three reasons. Nonetheless, these are salient issues germane to a strategy of geographic expansion. Bird (1989) discusses some of the key factors related to the diffusion of control, most notably, the "willingness" to delegate. The owners stated that each site was under local control, but, in fact, the interviews revealed an inconsistency between the owners' behavior and statements. For instance, the owners were criticized for too much day-to-day involvement in the affairs of the local sites. Unaware of what their actions were communicating, the owners were choosing to manage rather than lead the new sites, thereby keeping employees from developing fully. The phenomenon of managing rather than leading has been observed by Peters and Austin (1985) in a variety of settings. Management with its attendant images, such as "cop, referee, devil's advocate, and naysayer, connotes controlling and tight supervision" (Peters and Austin 1985, p. 17). Leadership, on the other hand, connotes unleashing energy, delegation of control, and employee nurturing, growing, and development. Given the lack of qualified personnel at the different site locations, it appears that the owners of LAC were unwilling to diffuse control to allow the distance sites to take on a direction of its own, no longer dominated by the intentions and will of the home office. This created considerable

- 20. 252 D.W. GREENING ET AL. conflict in the organization. If the owners had hired and trained appropriate staff, it may have been beneficial for the owners in developing a new management style for this growth, enabling the employees to eventually become self-managing. This would suggest that a small business owner pursuing geographic expansion must ultimately make a choice: either restrict firm growth to the point where close control can be maintained or follow the aforementioned prescriptions with regard to adequate hiring, training, and compensation packages to allow effective delegation and diffusion of control. This important contingency relationship to delegating or maintaining control is exempli- fied in the owner's comment, "you cannot decentralize unless you have qualified staff you can trust to do the job right." Discussions in the previous section highlight the importance of selecting the right people and properly training and compensating them. For example, the training process was critically important to the success of the start-ups. The training category received more comments than any other category in the interviews (all 17 respondents men- tioned it, and nine members mentioned it more than once during the interviews). This finding illustrates that one of the critical challenges that small businesses face is adequately training personnel previous to and during expansion. Earlier we commented on the owners' inability to divorce themselves from day-to-day management of the remote sites. It's difficult to clearly identify whether the owners' inability to "let go" or the problem of underdeveloped, unqualified staff created the control difficulties that were observed. Our prescription is to hire and train qualified staff to allow owners considering geographic expansion to develop the necessary trust to delegate concurrently. A particularly striking interpretation of the root cause of many of the difficulties experi- enced by LAC is that the owners who started the company 25 years ago as entrepreneurs made the transition to become effective managers. However, this managerial transition by the owners suggests that a new set of entrepreneurs to "start" the businesses and get them off the ground may have been more helpful in the new geographic locations. Instead, the owners attempted to function as professional managers from afar. It may have been a mistake to assume that what worked at the original location would perfectly fit the business environments of the new locations given their level of geographic dispersion. The managers of the new locations may have benefited from more freedom to innovate and to be proactive in creating LACs that fit their local environments. However, an important caveat highlighted in this study is the need for qualified staff to start and grow such a company. Why Grow? Past research has tended to dichotomize the reasons for firm growth into two categories: economic and personal (or emotional). In regard to the former, theorists have identified a number of valid economic reasons for firm growth, including economies of scale in production, power and position in the marketplace (Child and Kiesner 1981), reduction in resource dependencies (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978), the efficient utilization of resources, and survival (Kimberly and Miles 1980). In addition, small firms may strive to grow to achieve some visibility threshold or to overcome liabilities of smallness that can threaten their survival (Day 1992). Firm growth may also occur for emotional or personal reasons. For some individuals, the growth of their business is an extension of their own psyche. For these people, seeing their business grow is a highly rewarding personal experience. Other owners may increase the size of their business to make room for the employment of family members or for other highly personal reasons. One reason for growth that includes both organizational and personal

- 21. SMALL BUSINESS GEOGRAPHIC EXPANSION 253 reasons is an owner's desire for organizational self-realization; a manager's belief that his/ her firm should become a completeunit, make progress, and conquer new challenges (Starbuck 1965). Our interpretative case study further illustrates that small firm growth can be motivated by a combination of these reasons. As mentioned earlier, the owners (and original founders) of LAC were concerned about funding their retirement and, as a result, decided to expand their business for the purpose of wealth creation. This resulted in a decision that appeared on the surface to be strictly economic (expansion for the purpose of wealth creation) but was probably associated with the emotional concern for retirement security as well. From a theory-building perspective, this insight suggests that the common economic rationales for firm growth may be concomitantly associated with emotional or personal reasons more than the previously discussed dichotomous model (economic or personal reasons) sug- gests. In addition, the difficulties experienced by LAC illustrate that firm growth can be a difficult, painstaking process. Small firm owners considering expanding their business may wish to carefully weigh the potential benefits (e.g., wealth creation) against the potential personal and financial costs (e.g., longer work hours, emotional challenges, the possibility of the loss of money, and the several challenges listed in Table 1) before firm growth is initiated, or they may consider making appropriate personnel adjustments, such as hiring professional managers or consultants. From a prescriptive perspective, the case also illustrates the point that both economic and emotional or personal reasons for firm growth may motivate owners to expand the geographic scope oftheir business at a pace that outdistances their level ofmanagerial expertise. After 25 years in a single location, LAC expanded from one location to 17 locations in a period of two years. In retrospect, the owners conceded that they expanded too rapidly. What is telling about the experience of LAC is that geographic expansion involves more than simply replicating an existing business in another location. It involves starting up a business in a new location, which requires an understanding and learning oflocal system dynamics. Whereas the product produced for the new location may be identical to the product produced at home, many local situations are different, including competitors, the pool of available employees, the business climate in general, and various stakeholders (e.g., interest groups in one community boycotted an LAC site until they agreed to use only recycled paper). Clearly, a lack of awareness of these different issues frustrated the geographic expansion effort of LAC by creating ambiguity in the decision-making process. The normative implication of this finding is that experiential learning must take place (March 1981), and the pace of a firm's geographic expansion must allow for learning in the new environment. Through learning, skills and managerial knowledge can become congruent with the requirements of the local system. If it is not, frustration and performance below expectations is likely to ensue. This is a particularly salient point for "first movers" (i.e., businesses that attempt to reap above normal returns by being the first company to sell a new product or service). As a competitive tactic, a first-mover company may decide to expand fairly rapidly geographically to make a new product or service available in as many locations as possible before the competition has time to react. The experience of LAC, however, suggests that prior to engaging in this tactic, first movers should assess whether sufficient managerial expertise is available in-house or through other sources to support the pace of geographic expansion under consideration. Limitations of Study A potential weakness of qualitative case studies is the possibility of yielding theory that is overly complex and capturing everything in very rich detail in contrast to the "parsimonious

- 22. 254 D.W.GREENINGET AL. hallmark" of good theory development. Our attempt has been to condense adequately the richness of the data without losing the flavor, intensity, and meaningfulness of informants' descriptions to provide relevant, incremental theory development (Eisenhardt 1989, 1991). Conversely, another potential limitation of qualitative, case study research is the potential to build theory that is overly narrow, idiosyncratic, and lacking generalizability, not only to other organizations but to larger theoretical perspectives. Our study is indeed focused in that it targets a specific type of small business growth-that of geographic expansion. However, our results suggest a number of important growth implications. It remains for future research to test the extent that our findings generalize to other types of small business growth and to organizational growth in general. A final limitation of the study is that although the informants interviewed in this study appeared to be quite willing to discuss their concerns, one must always be aware that informants may not present the "entire story," although the use of reliability methods (i.e., frequency data) lessens the concern in our study. CONCLUSIONS It is critical to have a realistic plan and premise before undertaking geographic expansion. It is not possible, for many of the reasons discussed in this study, to simply replicate previous success in the initial location. Owners may assume naively that the understanding developed in their initial venture is sufficient to develop one or more remote locations. However, our results suggest that problems should be expected, and whereas solid planning should be undertaken, managers need to understand the need to learn during expansion and expect to make periodic adjustments to unforeseen problems. Although this appears to be a relatively straightforward prescription, Argyris (1991) has found that successful people have difficulty learning during potential failure, making adjustments more problematic than one might other- wise expect. Management style must also change during geographic expansion. Important decisions regarding the delegation of authority and management of new information and resources must be considered as well as new leadership roles. As entrepreneurs expand their business, they need to remember those important skills that led to their initial success as well as the new skills to lead their new ventures. REFERENCES Alexander, S., and Ruderman, M. 1987. The role ofprocedural and distributive justice in organizational behavior. Social Justice Research 1:177-198. Amit, R., Glosten, L., and Muller, E. 1993. Challenges to theory development in entrepreneurship research. Journal of Management Studies 30:815-834. Argyris, C. 1991. Teaching smart people how to learn. Harvard Business Review 69(May-June):99- 109. Berg, B. 1989. QualitativeResearch Methodsfor the Social Sciences. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon. Bird, B.J. 1989. Entrepreneurial Behavior. Glenview, IL: Scott Foresman. Bracker, J.S., Keats, B.W., and Pearson, J.N. 1988. Planning and financial performance among small firms in a growth industry. Strategic ManagementJournal 9:591-603. Bygrave, W., Fast, N., Khoylian, R., Vincent, L., and Uye, W. 1988. Rates of return on venture capital investing: A study of 131 funds. In B.A. Kirchhoff, W.A. Long, K.H. Vesper, and W.E. Wetzel, Jr., eds., Frontiers of EntrepreneurshipResearch. Babson Park, MA: Babson College, pp. 275-289. Child, J., and Keiser, A. 1981. Development of organizations over time. In Paul C. Nystrom and